Hugh Bamford Cott was born in Leicestershire, England, in 1900 and schooled at Rugby. He attended Sandhurst Royal Military College, studied at Cambridge and got a doctorate from the University of Glasgow. An impressive pedigree.

He then travelled South America and Africa, becoming fascinated by Nile crocodiles. But what’s really interesting is his abiding obsession with how not to be seen. This led him to develop the ground rules for camouflage.

The word probably comes from camouflet, a French term meaning ‘smoke blown in someone’s face as a practical joke’. In the natural world, camouflage is no joke but a matter of survival. Its dictionary definition is ‘a set of methods of concealment that allows otherwise visible objects to remain unnoticed by blending with their environment or by resembling something else’. Cott, whose attributes included zoologist, wildlife photographer, writer and skilled illustrator, put it more poetically: ‘In nature the visible and invisible dance back and forth with each other, depending on how much we have learned to see. The science and art of this magic merge into one at the moment we grasp it.’

And grasp it he did in a lifetime of work and a classic called Adaptive Coloration in Animals, written in 1940. It remains one of the most comprehensive discussions of the subject ever penned. It made him famous, not only among zoologists and naturalists, but among soldiers in the Second World War. It became probably the only book on zoology ever carried into the field of battle.

Cott categorised camouflage into concealment, disguise and advertisement. After years of staring at things, he broke it down further into obliterative shading, disruption, differential blending, high contrast, coincident disruption, concealment of the eye, contour obliteration, shadow elimination and aggressive mimicry.

The more he looked, the more he found interesting adaptive strategies. Polar bears merge, plovers disrupt their outline, stick insects disguise themselves (as, um, sticks), zebras dazzle, some fish and butterflies misdirect attention with big eyespots, anglerfish use illuminated decoys, cuttlefish produce a smokescreen, some antelope bounce to look stronger than they are, lizards puff up. The root reason, said Cott, is to provide creatures with a reproductive advantage: if they survive, they can leave more offspring.

One way to decrease the risk of detection is to look like the background, something Cott called crypsis (from cryptic). According to this principle, the more similar to the background the colours and geometry of a prey are in the eyes of a predator, the more difficult it will be for the predator to detect the prey – or be seen if you’re the hunter.

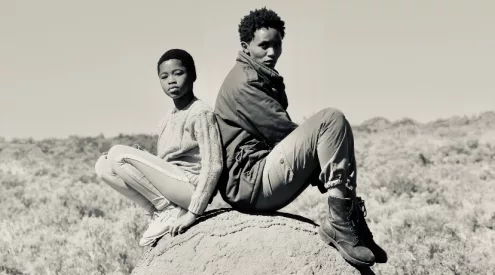

Another principle is disruptive colouration. Creatures (including humans) recognise objects by their outlines. If a surface is covered with irregular patches of contrasting colours and tones, these catch the eye and draw attention away from the shape that bears them. It can give the impression of separate objects instead of a repeated pattern on a single object. He called this mimesis (from masquerade).

Some colouration is so outrageous you’d think it would be an ‘Eat Me’ label. But camouflage, he said, works in mysterious ways. A zebra on a plain stands out like a burger joint, but in a moving herd, a lion (which is colourblind) sees a heaving mass and doesn’t know where to strike without getting kicked to pieces.

Many fish species are similarly camouflaged. Their vertical stripes may be brightly coloured, which makes them stand out to predators, but when they swim in large schools, the stripes meld together. This confusing spectacle gives predators the impression of one big blob. Generally, this sort of camouflage doesn’t hide an animal’s presence, it misrepresents it.

Mimicry is a different approach. Monarch butterflies are as gaudy as you can get, but poisonous because they sup on milkweed. Birds soon learn the hard way and have been known to throw up simply at the sight of a monarch. Other species of tasty butterfly mimic monarchs and are left in peace.

Two dead giveaways in camouflage, though, are shadows and eyes. If you’ve ever wondered why your cat flattens itself to the ground when hunting, it’s mainly to hide its shadow by lying on it. Lizards do the same. A variation of this ploy is called countershading, where the body’s upper part is darker (so as not to be seen from above) and lighter below (to be less visible from lower down). Most antelope have this shading. Many animals also have an uncanny ability to be motionless, adding to the impression that they’re part of the backdrop.

The roundness of eyes is a real problem as that’s where creatures (including humans) look first and there are very few perfectly round things in nature so they stand out. It’s probably for this reason, Cott speculated, that cats narrow their eyes when stalking.

Now here’s a big jump – stay with me. He published his book shortly after the outbreak of war and its value to military concealment soon became clear. He was drafted into the British Army as camouflage expert. A ragbag team of painters, potters, film-makers and even a stage magician were named the Camofleurs and formed the Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate.

Cott designed camouflage schemes to protect large targets such as airfields from aerial detection using techniques such as countershading and disruptive patterning. His work was also the basis of camo clothing.

As a zoologist interested in how things in nature seemed to vanish, his unusual passion took him far beyond the quiet Leicestershire neighbourhood where it began. What would he have given for Harry Potter’s invisibility cloak?