The Amathole Mountains are home to two precious species: the Cape parrot and yellowwood trees. Both are endangered, and the endemic birds need these trees. Janine Stephen visits an exquisite patch of forest to find this feisty pair.

Also read: 10 ultimate stays in Hogsback for nature lovers

Ah, to be able to fly. Instead, I’m careening down a steep path into Auckland State Forest, Hogsback, in pursuit of an elusive squawking creature. It smells so good here: a heady mix of damp earth and leaf litter, lemonwoods and tree breath; it’s a pity to run. But soon we arrive at a forest patch striped with enormous, cylindrical trunks: old-growth yellowwoods, stretching up like skyscrapers. The calls are louder now – they’re up there.

We scramble through undergrowth, necks craned at impossible angles, until, finally, there’s the patter of fruit falling on leaves. And there they are. Not in the yellowwoods, which aren’t fruiting, but in a wild plum, scissoring through kernels with zest (they have tongues like aliens) and shouting happily at the world. My first Cape parrots, Poicephalus robustus, ever. And some of the last 1700 on Earth.

Cape Parrots are very sociable and super-loud; they call continually when in flight and speak different ‘dialects’ in different areas. Photo by Rodnick Biljon.

The story of Cape parrots is tangled up in stories of yellowwoods, the giants of these Afromontane southern mistbelt forests, which extend in ever- decreasing patches from the Amathole Mountains in the Eastern Cape to bits of the former Transkei, into KwaZulu-Natal (around Kokstad and Karkloof) and Magoebaskloof in Limpopo. That’s pretty broken-up territory: the forests’ scope has decreased from about 1,5 million hectares to a third of that in the last century or so thanks to humans and their saws – and also possibly climate change. As the forests declined, so did the parrots.

Enormous yellowwoods, both the Outeniqua (Afrocarpus falcatus) and real (Podocarpus latifolius, South Africa’s national tree), play a key role in Cape parrot life. ‘That’s the tree that they love best,’ says my forest guide and Cape Parrot Project (CPP) research manager Cassie Carstens. ‘It provides them with food, nesting sites and social meeting places.’ They gather on dead trees called snags, from where they can see and be seen and tell everyone about it. Shy and solitary? Not Cape parrots.

Boscobel, the Cape Parrot Project’s HQ, is a hive of activity in laid-back Hogsback, better-known for waterfalls, fairy sculptures and Tolkien than an endemic parrot. There’s a specimen in the freezer, wrapped in plastic, a sorry found object. Its feathers are still bright green – an indication of general good health. It’s when the feathers start turning yellow that there’s a problem. Psitticine beak and feather disease is attacking Cape parrots; if it really takes old, the bird goes bald and its beak cracks and breaks, leading to death. ‘Basically, it eats parrots,’ Cassie says grimly.

The Cape parrot project put up hundreds of nesting boxes but so far they have been occupied mainly by bees and birds. Photo by Janine Stephen.

What’s not helping is poor diet, which affects their immune system. Parrots can’t find enough indigenous fruit year round – and the exotic plants they’ve resorted to eating, such as pecan nuts and acorns, ‘are like junk food’ for them. The solution is to plant more of their perfect food source: yellowwoods and other indigenous trees (they enjoy wild plum, Cape chestnut, ironwood and white stinkwood fruit). But making new forests isn’t about instant gratification: a yellowwood can take decades to fruit. And this is what the Cape Parrot Project is all about – parrots, and trees to sustain them.

In the grassland valley below Hogsback, Nomsebenzi Mayekiso is showing me her brood. Under shade nets are a couple of dozen rangy baby yellowwoods, soft leaves questing for light. It’s hard to imagine that they could stretch into behemoths like Hogsback’s Big Tree, an 800-year-old yellowwood 38 metres high and 6,5 metres fat. Micro-nursery growers like Nonsebenzi take in babies the CPP has germinated from seed and help them grow up; once they hit 40 centimetres, the CPP buys them back for R7,50 and plants them in areas they are reforesting (identified with the Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, or DAFF). She can also germinate and grow her own for R20.

It doesn’t make Nomsebenzi much money but every bit helps in a village where most people survive on grants and their gardens. She’s fond of her umkhoba (Outeniqua) and umcheya (real yellowwood) babies. She feeds them biological fertiliser and ensures they don’t get pot-bound. Watering is the bugbear: each tree needs up to 120 litres to grow to 40 centimetres, and Sompondo, her village, hasn’t had any municipal water for three months due to drought. To combat this problem the CPP built a community nursery with a water tank.

Welcome Sompondo is from the settlement’s original family; they’ve lived here since the 1920s. He says the parrots – iskhwenene – visit the fig tree we’re sitting under when it’s fruiting. Yellowwoods have traditional uses (for instance, bark boiled in water helps cure sick animals) and for certain ceremonies, meat is placed on its branches to be served. ‘We have respect for that tree, the big ones, like we have for those who have gone [the ancestors],’ Welcome says. ‘They take a long time to grow. We ask why did that tree become so big? Why that one?’

Yet the giants of the forest are under pressure – in some areas, at least – although real and Outeniqua yellowwoods are listed as of ‘least concern’ on the SANBI Red List. The CPP’s founder, National Geographic fellow and Wild Bird Trust director Steve Boyes, wrote to President Zuma in 2013, outlining their continued loss in the Eastern Cape. Communities have always harvested smaller saplings for poles, even though yellowwoods are protected and no one is allowed to cut them down. This means fewer trees making it to adulthood – although it is ‘relatively small scale’, says DAFF. But DAFF also allows big yellowwoods to be harvested annually, ones that are dying – exactly the ones the parrots need for nests.

A Cape parrot. Photo by Cassie Castens

‘Big trees may only be harvested if they are in the last cycle of their lifespan – either dead, trees that have lost more than 70 percent of their crown, or trees with more than 90 percent die-back,’ according to DAFF. Harvesting is only allowed in about 3000 hectares of the Zingcuka and Keiskammahoek, a ‘small portion’ of the overall forests. ‘There are 132000 yellowwood stems in this area, and only one percent may be harvested per annum’.

Still, that’s 1320 trees a year – which take hundreds of years to become giants. How sustainable is this? According to Steve, ‘Any harvesting threatens these forests and the endemic species like the Cape Parrot that depend on them … there is no doubt that it’s not sustainable, at least for the next 50 to 100 years.’

The illegal harvesting is harder to keep tabs on. Yellowwoods are poached for valuable timber. ‘The poisoning of large yellowwoods in the Amatholes using diesel or ring-barking has been reported for decades,’ says Steve. ‘Evidence of long-term damage to older trees to slowly kill them and facilitate their harvesting was reported by [DAFF] staff in King William’s Town in 2011. That same year we found over 50 large yellowwoods had been illegally removed from the Wolfridge Forest.’ DAFF acknowledged at least one case in 2016. Up in KZN, a man was prosecuted in 2008 for paying R10000 to a local chief to allow him to chop down yellowwoods in the Gongqo-Gongqo State Forest in Umzimkulu. They felled 89 trees, each up to 400 years old.

Steve says they’ve heard of ‘large trucks carrying unmarked yellowwood logs and of large piles of logs lying next to the road late at night’ in the Amatholes. (This activity had been reported as recently as the week before I arrived by the chairman of a local housing association.) Of course, parrots too are poached and sold into the pet trade. They used to be seen as a subspecies of the grey-headed parrot, but were declared genetically unique in 2015. Immediately, collectors and breeders wanted them.

Cape parrots like to feed and nest in high-altitude forest. That’s why you don’t find them in the Knysna forests, despite yellowwoods growing there. Photo by Cassie Castens

Other threats to the trees include fires, drought and commercial forestry (which sucks up available water). All in all, what’s left needs protecting, badly. According to DAFF, the 218-hectare Auckland Forest Nature Reserve has strict protection with no harvesting but the other areas are state forest. ‘These do not have strict levels of protection. The forest nature reserve makes up less than five percent of the forest area. The CPP is working with DAFF and Eastern Cape Nature to identify areas where forest nature reserves can be expanded.’

Steve would like to see all trees over 100 years old recorded – and the CPP believes there’s a need for independent observers to monitor any harvesting.

It’s a bright day in Hogsback and we’re at a gathering of the Hogsback Garden Club. On the table is a cake expertly iced with an image of a Cape parrot. I recognise some of the crowd from the Saturday morning market – it’s that kind of town. The CPP is here to present its work, and persuade locals to plant indigenous. Aliens line Hogsback streets and burst luxuriantly from gardens. Its Arboretum, in which enormous Californian redwoods stretch to the heavens, is full of alien trees planted by colonial forestry officials – ‘tests’ to see what grew best.

The CPP wants to plant 5000 indigenous trees this year, and germinate 50000 at the nurseries in Sompondo and Boscobel as well as through micro-nurseries. When the talk is over, club members head to an area called The Bluff and plant yellowwoods. This is a new ‘feedlot’ for the parrots: not official reforestation, but a dense patch of thousands of trees that will eventually act as an additional larder. Ideally, if locals all plant indigenous, the whole town will become an integrated feedlot.

Later, I sit at the viewpoint at Away with the Fairies Backpackers. The forest lies inscrutable beneath me, yellowwoods bursting through the canopy like popcorn. I recall Cassie’s description of the parrots: ‘They’re very complex and they’re taking complete control of my life!’ He’d told me about catching a few to take samples, and how they’d twisted themselves into the nets in fury and had to be cut out. And then how they’d fought tooth and nail. ‘They try and eat you. We got three birds, and it was an hour-and-a-half of mayhem. You need proper leather working gloves and plastic gloves over the top. So yes, they are strong, hard birds.’

Round about then, the dusk was rent with squawks and calls, and streaks of green bulleted overhead. Fantastic creatures in an enchanted forest. I just hope they’re tough enough to make it.

The Madonna and Child waterfalls – seen on one of several Hogsback forest walks that encircle the town. The remains of an old saw pits can often be seen in the forest; the Amathole Mountains are the Cape parrots’ major stronghold – over a third of those alive today live here. Photos by Melanie van Zyl

Over in Cape Town…

One place where Outeniqua yellowwoods are expanding their range is in Cape Town, in the Kirstenbosch/Newlands area. They’re spreading so fast here thanks to birds eating the fruit, says Adam Harrower of SANBI, that he can imagine them becoming problematic. They are even being grown in sandy soils in Epping, on the Cape Flats. Of course, how many will make it to become over 400 years old is another question. (According to some sources, Cape parrots were last seen near Cape Town in 1726.)

Plan your trip

Getting there

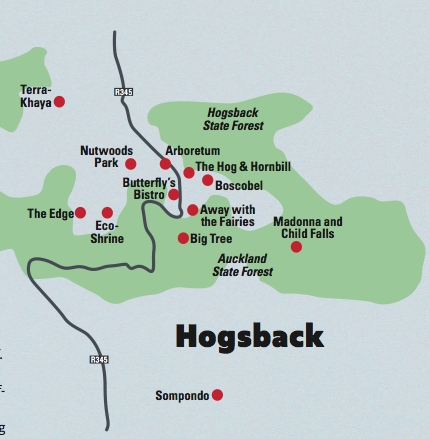

Hogsback is about 150km from East London, via the N2, R63 and R345 (or 263km from Port Elizabeth via the N2 and R67). I flew Safair to East London from Cape Town for R1200.

Need to know

Parrots are most active at dawn and dusk (the yellowwoods, thankfully, stay put). The birds are here all year round, but large flocks are most likely seen in January and February. Other sites in South Africa worth visiting are the Ingeli Forest on the N2 between Kokstad and Harding, Hlabeni Forest in the Creighton area (170km west of Durban) and Magoebaskloof in Limpopo (80km east of Polokwane). For more info on the Cape parrot, or how to get involved, visit wildbirdtrust.com.

Stay here

Self-catering cottages at The Edge Mountain Retreat have incredible, sweeping views. Photo by Melanie van Zyl.

a double room.

The Edge Mountain Retreat is on the edge of a gorge, with some cottages right on the cliff. It has a popular restaurant and 1,4km labyrinth to explore. Self- catering cottages (from R650) or rooms (from R300 per person sharing B&B).

Do this

Find those parrots. A local birding guide is Graham Russell. R300 per person for a three-hour forest walk. 0823746583

Plant a tree. Greenpop hosts an annual tree-planting festival in September at Terra-Khaya. But you can plant trees here year round (if you plant five, you get free dinner!)

See the Big Tree in Auckland State Forest, an easy 45-minute walk from the town centre, or as part of a longer hike ending at the Madonna and Child Falls with a steep ascent to Wolfridge Road. Yellowwoods abound.

Visit the Eco-Shrine in a lovely garden with views of The Hogs peaks. Diana Graham, who built it, will give you a personal tour. R30 entry.

Admire the Arboretum, which was Hogsback’s first garden, established in the 1800s by the British. There’s a pretty waterfall called 39 Steps, and the Californian redwoods are spectacular. Free entry. (Traders who sell the traditional clay hog souvenirs can be found here.)

Have a hot bath with a view over the forest at Away with the Fairies Backpackers. R50 (plus R20 for eco-friendly soap). Booking essential. 0459621031

Eat here

Butterfly’s Bistro does good pizzas (from R60), burgers (R85) and vegetarian food, and is the venue of the Saturday morning farmers’ market. 0459621326

The Hog & Hornbill is Cassie’s local. It has a nice garden and serves pub grub, snack baskets and craft beers. 0736004644

Nutwoods Park offers fine dining in an elegant candlelit room. Book ahead for dinner, R270 per person. 0459621043

This story first appeared in the November 2017 issue of Getaway magazine.

Our special green issue features the best off-the-grid campsites, fantastic holiday stays in Wilderness, an affordable jungle trail in Borneo, incredible eco-lodges in Zanzibar and our Green Wine Guide is finally out with winners!