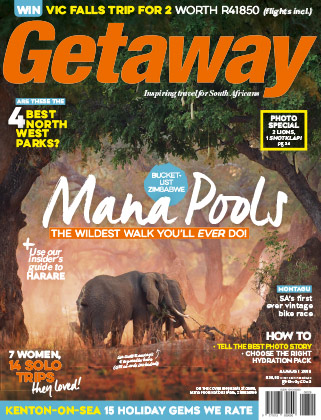

If you walk in Mana Pools, Zimbabwe, you will be changed, they say. But like any sacred space, you must tread here with great respect, writes Scott Ramsay.

The bull elephant walked straight towards us, slowly moving through the canopy forest in Mana Pools National Park. His huge feet trod the earth gently, leaving a trail of dust illuminated by the late afternoon sun. My guide, Stretch Ferreira, whispered for us to sit on the ground. We’d been walking on the floodplain that afternoon and Stretch – a professional guide of 30 years in Mana – had hoped to find this bull. They’d known each other their whole adult lives. And Stretch wanted us to meet him.

Now Earth’s largest land animal stopped just before us, within touching distance, his long tusks within a metre of our faces. I looked up slowly at one of his large eyes and for some reason averted my gaze quickly. My heart pounded inside my chest. It’s a strange, unique sensation: being enthralled and terrified at the same time.

LEFT: Stretch Ferreira and some guests pay their respects to a king in Mana. RIGHT: Elephant bull browsing on an albida tree.

My hands were shaking, so I did my best to take a few photographs. With the tip of his trunk the elephant scooped up some fallen seedpods that had dropped from the albida trees and crunched them between his molars. Psychologists talk of a state of flow. These are moments when your mind becomes entirely absorbed in an activity so that you forget yourself – and everything else. There’s a heightened sense of awareness of the here and now. Nothing else matters other than what’s in front of you. Time seems to stand still, yet it also speeds by. This was such a moment. After a while, I’m not sure how long, the elephant shook his trunk slightly, flapped his ears a few times to keep cool and then walked off to browse on a nearby tree.

Mana’s magic

Despite a tragic increase in poaching, elephants still roam across many protected wild areas of the continent. But while Serengeti, Chobe, Kruger and Gonarezhou all boast impressive elephant territories, Mana could be their headquarters, the heart of their dwindling empire of Africa. The floodplains on the southern bank of the middle Zambezi Valley are unique in their ecology, beauty and atmosphere. This achingly photogenic place is made for the king of Africa’s creatures. And for visitors – especially wilderness lovers – it is one of the finest parks on the continent.

‘There is a sense of remoteness and extreme isolation, a feeling that this is one of the last true wildernesses, unknown and unexplored,’ wrote Dick Pitman, a long-time admirer of Mana, in his book Wild Places of Zimbabwe. ‘It is almost entirely unmodified. Down here, the wilderness still rules and man must still obey it to survive.’ Regular visitors to Mana speak of it in reverential, hushed tones usually reserved for spiritual matters. Walking here is not simply a holiday – it’s a wilderness pilgrimage. If you go, they say, you will be changed. I have been, several times, and I have changed. Spending time in any wilderness recalibrates my perspective on life. But Mana always seems to open up new, uncharted pathways into my soul. It is the only national park with big game in Africa where anyone can still walk freely, either unescorted or with a guide or national parks ranger.

Later that evening we ate dinner and drank cold Zambezi lagers at Stretch’s tented camp on the banks of the river. Stretch is like an old bull elephant himself: broad, tall, lumbering, sometimes aloof but always clearly in charge of his territory. That evening, leaning back in his chair and scratching his ginger beard now and again, he spoke of those special moments that stand tall in his memory.

‘I was once sitting under an albida tree with a female guest, watching an old elephant bull who I had known for 20 years. He was slowly feeding towards us and so I told my guest to sit quietly next to me. ‘The bull walked to within a few feet of us. He then gently picked up his foot and slowly moved my guest aside to eat the pods she was sitting on. She wasn’t hurt at all. Just had a slight abrasion on her arm, from the rough skin on the elephant’s foot. My guest remained calm, fortunately. For both of us it was a life-changing moment. There was immense trust between man and elephant.’

Then there was the time that Stretch witnessed an elephant giving birth to its baby, right next to him. The calf dropped to the ground in its fetal sac, which the mother then removed with its trunk. But the baby was still not breathing freely, so the mom then kicked dust into the air. ‘The little elephant then promptly sneezed,’ said Stretch. ‘Perhaps the sneezing cleared the mucus from its nasal passages so that it could breathe properly?’

Mana is also famous for its lion sightings. Stretch once watched a group of six lionesses battling to take down an adult female buffalo, only to give up eventually, leaving the buffalo alone. The pride male then arrived. ‘With one swipe of his paw, he managed to bring this big buffalo down on his own, something six lionesses couldn’t do,’ Stretch explained. ‘That kill would have fed the whole pride. This is why we should continue to vigorously oppose the hunting of lions. Without them the apex of the food chain will be destroyed and the entire ecosystem will be affected.’

In Mana, lions are mostly used to groups of walking humans, but they should only be approached in the presence of an official guide or parks ranger.

Walking ethics

Witnessing such moments is rare while walking in Africa. Usually, wildlife will move away as soon as a human approaches on foot. Thousands of years of hunting have ingrained in the creatures a healthy distrust of people. However, in Mana, animals are so used to seeing Homo sapiens walking that the wildlife is mostly unperturbed. But in recent years, Mana’s legendary wildlife and walking terrain have begun to draw more and more visitors, some of them different from the traditional wilderness aficionado.

‘Mana was becoming a free-for-all,’ explained Richard Maasdorp, the director of The Zambezi Society, a non-profit conservation organisation with decades of involvement at Mana Pools. ‘There were big groups of unescorted walkers, mostly photographic groups. They were using radios, tracking animals, and would often surround the animals, especially wild dogs, for long periods of time. They’d use their 4x4s to drive off the designated tracks, and generally not show any respect.’

The parks authority took the decision to ban all unescorted walking, to the disappointment of many of Mana’s longtime devotees. The bad behaviour of a few had spoilt it for the majority of people who do respect wildlife. The Zambezi Society sponsored a research survey that showed that most visitors wanted unescorted walking reintroduced. After several months of negotiating with Zimbabwe Parks & Wildlife Management Society, the ban on walking was lifted. But, Richard explained, it could be reinstated if visitor behaviour doesn’t improve dramatically.

‘There is a general attitude among South African visitors, in particular, that they can do what they want,’ said Richard. ‘Of the walkers who don’t respect wildlife, about 80 percent of them are South African. If the unethical behaviour continues, then walking could be banned again. But the parks authority also has the option of banning South Africans from unescorted walking.’

A walk with ranger Tendai Sanyamahwe from Nyamepi into the floodplains of Mana ranks as one of my best experiences.

On another visit to Mana, I hired park ranger Tendai Sanyamahwe to guide me on my walks. Few guides can match Tendai’s enthusiasm for and commitment to the protection of Mana. The 49-year-old with a hardened gaze and ready smile works mostly on anti-poaching patrols, spending weeks at a time criss-crossing the 2100-square-kilometre national park. Early one morning, within 15 minutes of walking from Nyamepi along the floodplain, Tendai raised his hand and motioned for us to kneel down. He pointed into the shadows of a thick bush, about 40 metres away.

A lioness’ eyes locked on to us. Then the cubs. Three of them, playing nearby. The mom called them and they came running back to her, bouncing on top of her broad back, pulling her ears with their sharp little teeth, oblivious to our presence. We sat and watched their antics for a while, then backed away. We strolled through the shaded canopy albida forest and admired a small breeding herd of elephants with babies. Next up was a statuesque eland bull, defiant and proud like a Michelangelo sculpture. Behind him several old buffalo bulls raised their nostrils at us, grumpy as ever, looking in desperate need of a strong cup of coffee. Tendai then guided us to Long Pool, one of Mana’s four big inland pans that hold water during the dry season. We sat on the high bank and watched a large pod of hippos grunting and groaning. Cohorts of crocodiles lay basking in the first rays of sun. And always the baboons – the jesters of Mana – flinging themselves around the trees above us.

Pools of summer water remain throughout Mana’s dry season, giving hippos respite from the heat.

The hinterland

Mana’s floodplain extends 35 kilometres along the Zambezi River and five kilometres inland. It offers the most popular, accessible walking, but much of the park is set away from the Zambezi. Here vast mopane woodland extends south towards the high escarpment mountains in the south. It is a very different walking experience: hot, dry and rugged, but arguably wilder than the shaded, manicured atmosphere of the albida forests on the floodplain. But, accompanied by a guide or ranger, these areas are ultimately as rewarding. Often the water draws amazing encounters with wildlife in the dry season. A well-known waterhole is Chitake Springs in the south of the park, a legendary area with few campsites. In the dry season, it draws herds of buffalo and several attendant lion prides.

Guide Nic Polenakis has worked regularly in Mana since 1995 and remembers one particularly memorable walk nearby. ‘I was walking with guests along a deep gulley and happened to look up into one of the big trees. My heart skipped a beat because a few metres above us was a huge male lion perched on a big branch. He was watching us, very relaxed. We moved back a bit and watched the big boy dangling in the tree.’

There are many other pans too, hidden away, only known to the experienced guides. ‘I once got permission to walk at night with guests to a remote pan,’ said John Stevens, who has worked as a guide in Mana since 1986, when black rhino still roamed before poachers wiped them out. ‘We found a pan with water and sat and waited on one of the termite mounds. As it got dark, the first black rhino arrived and wandered straight into the water to drink and cool off. He seemed very relaxed, so I mimicked the call of a black rhino. He came slowly up to us, right to the base of the termite mound, moving his head side to side right in front of us. Then he walked back to the pan, rolling in the mud.

‘Three buffalo bulls arrived and confronted the rhino. It was buffalo versus rhino! The full moon was silhouetting them. Two buffalo backed off, except one of them, which dropped its head right next to the rhino’s horn. ‘I was expecting an almighty confrontation, but instead the rhino placed his horn on the boss of the buffalo and they started gently scratching each other!’

Water hyacinth may be pretty, but they are invasive plants from South America that threaten the surrounding ecology.

While poaching in Mana is not as severe as in some other wild areas in Africa, the killing is increasing. This makes the experience of walking in Mana even more poignant. This is a true wildlife paradise on the edge of survival. Every animal and every tree seems extra precious when viewed in the context of the general destruction of Africa’s natural world. ‘It’s a huge privilege to walk here, in one of Africa’s finest remaining wild places,’ Richard emphasised. ‘We must never take it for granted.’ On our last evening, camping on the edge of the Zambezi, a bull elephant walked straight up to our fire. My friend and I stayed put, not moving from our chairs. For a minute or so, the bull sniffed us with his trunk, within centimetres of our bodies. I could see his toenails clearly, illuminated in the firelight. Another moment of flow, when time seems to stand still.

Getting here

From Harare, drive north on the A1 tar road through Lions Den (S17°15.915’ E30°01.051’) where there is a great roadside restaurant with coffee and excellent bacon and egg toasted sandwiches. Continue to Karoi (S16°49.064’ E29°41.015’) and buy extra supplies or fill up with fuel, as that’s the last main village before Mana. From there, drive to the parks office at Marongora (S16°13.387’ E29°09.683’) where all visitors need to sign in, before heading down the escarpment pass to the turn-off east to Mana (S16°11.337’ E29°09.684’). From there pass through Chimutsi (S16°11.324’ E29°09.724’) and Nyakasikana (S16°03.360’ E29°24.554’) gates and head north to the parks office at Nyamepi (S15°43.411’ E29°21.662’). The drive from Harare to the office takes seven to eight hours, with stops.

When to go

Mana is best during the dry season, from April to November. September to November can be very hot and humid, but this is also when wildlife concentrates on the floodplain and at pans.

Need to know

The daily conservation fee for visitors is R228 pp. There’s also a one-off vehicle fee of R152 for a five-day stay. A 4×4 is highly recommended. Walking unescorted in Mana is only for the very experienced. While the wild animals are more used to humans than those in most other national parks, it’s safer to hire and walk with a ranger. My favourite ranger was Tendai Sanyamahwe. Or stay at a private camp and walk with one of their guides, such as Stretch Ferreira (Goliath Safaris), Nic Polenakis (African Bush Camps) or John Stevens (John Stevens Safaris).

Walking in Mana

To walk unguided in Mana costs R152 per day for Zimbabweans, R228 per day for foreigners. To hire a guide costs R76 per person per hour for Zimbabweans, R152 per hour for foreigners. Maximum group size is six. For fewer than three people, the minimum cost is three multiplied by the per-person rate.

Stay here

Nyamepi Camp, with 30 sites, is a public campsite near the Mana Pools National Park reception office. There are ablution blocks and visitors can buy firewood at the office. My favourite sites are1and2,bothonthe river with shade, and set slightly away from the other sites. From R1 745 per night for six people. There are also several exclusive sites (up to 15) on the river that allow only two vehicles and up to 12 people per group. Mucheni, Ndungu, Gwaya, Trichilia and Nkupe are five of the favourites. Chitake Springs also has three campsites. From R2 609 per night for six people. +263772432148, zimparks.org

Some private companies offer exclusive luxury camping and lodges, with guided walks. Prices are higher (from R3034 per person per night), but are generally all-inclusive and the standard of guiding and accommodation is commensurate. These are some of the most experienced operators: Goliath Safaris +263-772-733-252, goliathsafaris.com; African Bush Camps (Kanga Camp) 0217010270, africanbushcamps.com; John Stevens Safaris +2634494313, johnstevenssafaris.com; Wilderness Safaris 0118071800, wilderness-safaris.com.

This story first appeared in the August 2016 issue of Getaway magazine.

Our August issue features Mana Pools, great North West parks, and best trips for women. On shelves from 25 July.