After six days in the bush I wasn’t expecting any surprises, that’s what comes from being driven around all day by a khaki-clad bush-oracle armed with a .458.

Plus Abel had forgotten about this part of the tour. We were already on our way back to Shiluvari Lakeside Lodge on the eucalyptus and fever tree-clad shores of Albasini Dam in northern limpopo when he slapped his forehead and said, ‘the hospital, we forgot the hospital’, which is quite a feat for a tour guide in Elim, because the historical hospital is the thing to see, it’s Elim’s Alamo and giant koeksister all rolled into one, the hook on which regional history hangs, the area’s major employer even today.

Deciding to visit Elim hospital is one thing, getting in quite another: at the gates visitors are asked to exit their vehicles, which are thoroughly searched inside and out, before the human occupants are spread-eagled and hand-scanned.

‘A disgruntled patient came back not so long after he was discharged and held up his doctor,’ explained Abel, and added that exiting staff are also searched, ‘because this hospital bleeds, man, it bleeds—computers, drugs, you name it.’

It was obvious the situation irked Abel, both the fact that there were grounds for the search but also the implied distrust. ‘I used to live at Elim hospital, in that building over there with the red roof, you’d think they’d treat me differently,’ he complained. ‘And as for the museum, you’ll see it’s in a terrible shape, but the work that has been done to date: the sanding of the woodwork, the arrangement of certain implements and machines… I did that in my student years with my friends, not for money but because this is the region’s heritage, and it’s my heritage. Sadly, it has proven very difficult to get anyone else to care about it, including the national heritage agency and the hospital administration.’

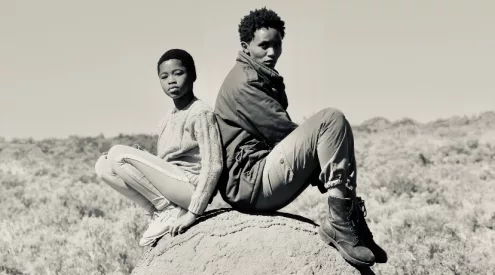

Abel’s very short biography is important here and goes like this: his baptised name is Hlupheka Abel Baloyi. He’s a tour guide and 20% owner of Kuvona Cultural Tours, started by Paul Girardin, who owns a majority stake, and Paul’s brother Michel, who owns a 30% stake and who happens to own the majority stake in Shiluvari Lakeside Lodge with his wife Clare. The Girardin and Baloyi families go way back—Michel and Paul’s Swiss missionary great grandfather, George Liengme founded the hospital, the first hospital north of Pretoria, over a hundred years ago. In years to come the Girardin and the Baloyi families settled the same farm and co-existed excellently as, until it was expropriated by the government, which at the time actively looked for examples of harmonious racial co-existence, and stamped them out. Homeless, the families lived at Elim hospital for a time, and listening to Abel speak it was becoming increasingly clear to me that the ties between the families, and between the families and the hospital, persist to this day.

‘Hlupheka means unlucky, because I was born at a time when we didn’t have much in the way of money or security,’ said Abel. ‘But I consider myself lucky—I was lucky enough recently to get a tour group that paid for me to fly to Germany to spend 6 months learning German.’

‘And, how did it go?’

‘Ich verstehe nicht alles,’ Abel joked (I don’t understand a word).

Abel’s revival of spirits was dashed, however, by the security guard’s insistence that he accompany us wherever we go. The man wore a canary yellow shirt with airplane captain epaulettes, and seemed happy to be away from the gate for a time. He also eagerly supplemented with colourful gossip Abel’s criticisms of the state of the national monument and of the integrity of Limpopo’s administrators in general.

‘I can explain the hospital’s history but I’m afraid I have no clue what all of this stuff was used for in its time,’ said Abel, picking up a pair of curved tongs that came apart in his hands.

‘Boetie,’ he addressed the security guard, looking skywards with a puzzled expression, ‘who replaced these bulbs?’ ‘The hospital. And they polished the floors. It’s because the Swiss Ambassador was here yesterday,’ the guard explained, mischievously.

Indeed His Excellency was also staying at Shiluvari, which he’d chosen as the host venue for several meetings he’d been conducting with local bureaucrats. A chance meeting with Michel last December got them talking about the Swiss history in the area, about the hospital and the school Girardin’s forebear founded. These institutions have been in decline for many years Nothing has happened since and so the Ambassador has taken it upon himself to pick up the slack, of which one immediate consequence was the hasty polishing of a floor. Not that this disguised the building’s dilapidation. Abel’s mood went from bad to worse as he opened display cabinet after display cabinet to find that the implements inside had been stolen, ‘by interns who used to have access to the building’, he claimed.

‘This is an interesting room,’ he said approaching a closed door, but when he tried the jamb it wouldn’t budge, and it turned out the key had been removed from the guards’ bunch.

‘What are they storing in there,’ Abel demanded.

‘Pension files,’ said the guard gleefully.

We wandered right to the back of the old hospital building and entered a room in which there had been no attempt to arrange any sort of medical diorama. It seemed the odd little tour was at an end but Abel suddenly remembered something.

‘Oh yes, we even babies stored here…no, not babies, what do you call the aborted babies?’

‘Foetuses?’

‘Yes, Foetuses! In Formaldehyde, like you maybe had once at school.’

Queasy by nature, easily spooked, I would certainly have avoided the room if we hadn’t already drifted in. There in the gloom against the far wall were four shelves, each supporting five or six glass jars containing formaldehyde of various hues and at varying levels. Staring out of these solutions were human foetuses, looking for all the world like a family of inquisitive gnomes. ‘I’m very worried about these,’ said Abel. ‘You see anybody can open this wall here and steal these babies for use as muti.’ He pulled on the board that constituted the wall of the room. Sunshine flooded in and a passer-by screamed, which reduced the security guard to hysterics. ‘She thought it was a ghost,’ he tittered.

It didn’t take us long to exit the hospital after that. We stood out on the road and Abel said he hoped that something good would come of the Ambassador’s visit, that he hoped the museum would get a curator and that the theft would stop, so that children could come and learn ‘that there were Swiss people here who did these things for this area.’

‘Right now you can’t bring anyone—no children, no tourists…the place is a disgrace,’ Abel spat but then seemed to reconsider.

‘I suppose you’re a tourist and what you’ve seen is the reality of Limpopo, something not many people see.’

It could have been a calculated denouement, something Abel tells all his clients, but that seemed unlikely and neither does it make his statement less true. This, I thought, is how you guide.

To read more about FTTSA and see a list of all certified businesses go to www.fairtourismsa.org.za or join FTTSA on Facebook.

To receive a quote or book a vehicle with Avis go to www.avis.co.za