Abu was looking at me with impish delight in his eyes and smile. I had just arrived on Medjumbe Island, and he was leading me to my beach villa. I realised he was not merely being friendly but pointing to something on the path. I looked down and there were several shells in the sand, scurrying out of my way! Hermit crabs. Once he’d drawn my attention to them, I saw them everywhere.

The sand spit is clearly visible from the air – it’s a one-kilometre walk to the tip. Image credit: Justin Fox

That night, it was the somewhat larger ghost crabs that accompanied me back up the path to dinner, most side-stepping out of the way but some seeming to stand their ground, playing chicken with me, for a few seconds longer. On late-afternoon walks on the beach over the next few days, crabs were my amusing companions, scuttling in crazy directions along the shore before being swept off track and tumbled around by the incoming tide.

It’s hard to say exactly how big Medjumbe is – low tide reveals a skirt of dazzling white beach, extending out on the southern side of the island along a one-kilometre sandbar. At high tide the island shrinks and the surrounding water takes on several additional hues of blue and green. It’s big enough for 12 beach villas, a lodge with a pool, a 600-metre airstrip, a helipad, a field of solar panels and staff accommodation. The total population of this private island, excluding guests (maximum 24), is around 12 people. Almost all of them were on hand to greet me when I arrived – the start of the VIP treatment that continued all through my stay.

Getting to Medjumbe is a thrill in itself, a 40-minute helicopter ride hugging unspoilt coastline and passing over several of the Quirimbas islands. Still, a flutter of extra excitement ran through me on first spotting the specific speck in the vast blue ocean I’d be staying on.

The ‘castaway chic’ lodge blends in well. It has a lounge, dining area and library (in the loft)

Coming to a place like Medjumbe means slowing down and savouring each day. From dawn to dusk, the experience is dictated by nature’s rhythms. The tides, the weather, the time of day all determine what is possible – the perfect intersection of all three of these (a relatively rare occurrence) means grabbing opportunities when they arise. This might mean a dhow cruise at sunset, a noon snorkelling outing, dinner on the beach with table and chairs sculpted from sand. It’s about living in the moment – tomorrow, the tide may not be right, or it might be too windy…

Of course, one can do nothing but swim, sunbathe, stroll, snooze and repeat, throwing in the occasional massage or spa session. The only thing keeping you vaguely on track is meal times – and cocktail hour. In many respects, the food is one of the highlights of a stay here – including abundant seafood bought from the local fishermen on the mainland. Dinners kick off with breads and ‘tuna butter’ (dangerously addictive) and a chilli relish (dangerously hot). Even breakfast came with a starter: a pretty platter with a pastry, fresh fruit and shot glass of Bircher muesli.

It didn’t take long for the staff – I dubbed them the Four A’s: Almeida, Analito, Arlindo and Abu – to read my thoughts; they took note of my preferences and habits, and would offer a cup of tea – Ceylon, with milk – with breakfast, or a gin and tonic (instead of wine) with my dinner. They always brought still instead of sparkling water to the table. I never had to ask.

All of this fine food in abundance means that it’s advisable to take occasional exercise. There’s kayaking, windsurfing, waterskiing; I could, if I really wanted to, jog along the runway. I found other ways to happily tire myself out. From the air, I’d seen a thin white tower on the northern tip of the island, and set out for it on a post-lunch stroll. It was a weather-beaten lighthouse, the steps no longer climbable and the light no longer operational. It looked ancient. I was surprised to find out it had been built in the 1930s.

At the bar, there is always a ‘cocktail of the day’ on offer, and a perfect view of the sunset.

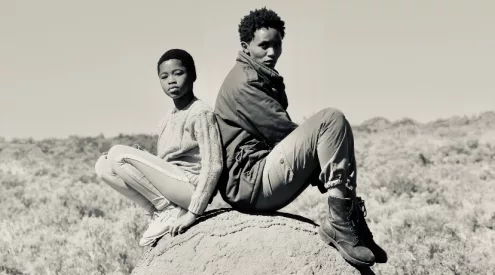

On the opposite side of the island was the spit – a wonderful sand corridor with water lapping on either side (a bit like the parting of the Red Sea) and black herons, sacred ibises and crab plovers for company. Around the corner from the spit, on the leeward side of the island, were the flatter waters where I tried stand-up paddling one morning.

A 10-minute boat ride took me to the coral gardens. There are more than 48 kinds of healthy coral here, in all shapes, sizes and colours. As I floated along, it was easy to imagine I was hovering above a fantastical city, where the busy inhabitants – mostly small reef fish – darted in and out of the corals or swam next to me. Vino, my snorkelling guide, pointed out an indigo starfish on the sandy bottom, a big lobster hiding in a cranny, a red-and-black striped eel and a large open clam that he touched to close it.

That was just a taste of the marine life – there are two other snorkelling spots straight off the beach, and nine dive sites surrounding the island. The scuba diving is fantastic here; most magnificent is ‘The Wall’, a drop-off into the depths of the Mozambique Channel. From July to September, it’s possible to see migrating humpback whales. It’s also a feeding area for turtles and a nursery for dolphins (the entire Quirimbas is a protected reserve).

Dhows are used to bring most of the provisions to the island, and are also on hand for sunset cruises.

When Medjumbe has been thoroughly explored, guests can hop across to Quissanga, the neighbouring islet that beckons tantalisingly. It took me half an hour to stroll around it, stopping to admire the corals and shells the tide washes up. Lunch awaited at a table set in the coconut grove in the middle of the island, a serene spot bathed in an ethereal green-yellow light filtering through the palm fronds. As I tucked into fish kebabs, I thought happily that a more atmospheric restaurant would be hard to find. There is also a ‘room’ on the island, a thatched, open-walled structure with carved-wood furniture and a bar counter. Medjumbe’s guests who come for a picnic often end up staying the night – there’s also a four-poster ‘star bed’ swathed in gauzy curtains.

The Quirimbas is a special, far-flung place. There are 32 islands in the archipelago, which stretches for 322 kilometres along the far-northern coast of Mozambique. Only a few of them are inhabited (some with just a simple fishing village), linked by the slow passage of dhows. Three of them – Matemo, Quisiva and Ibo – have historical attractions and that compelling East African Swahili vibe. Ibo, the largest, has an ancient Stone Town. The Quirimbas tourism mandate is for minimal impact on this pristine region, which means there are only a handful of places to stay and mainly on Ibo (generally, the more affordable options). Staying on a private island, as I did, is a dream come true.

When you’re going with the flow, things tend to come full circle. On the day of my departure, the same group who had first welcomed me here waved me farewell – except for Abu, who, with his impish smile, hopped into the helicopter with me.

Plan Your Trip

Stay Here

Anantara Medjumbe Island Resort has 12 gorgeous thatch-and-timber beach villas (with plunge pool and outdoor shower) just steps from the ocean. It’s an exclusive private island but the feeling is simple, beachy and natural, not glitzy or ostentatious. It costs from R7,935 per person sharing, including all meals, most drinks, non-motorised water activities and return air transfers from Pemba. Additional activities range from R690 per person for a dhow cruise to R830 per person for the island picnic. 010-003-8977, anantara.com

Getting There

I flew to Maputo, then to Pemba on the new Ethiopian Mozambique Airlines and returned on LAM; from around R1,600 per person. ethiopianairlines.com, lam.co.mz This works out cheaper than flying direct to Pemba from Joburg. It’s worth staying in Maputo for a night or two; Dana Tours can help organise this. danatours.com