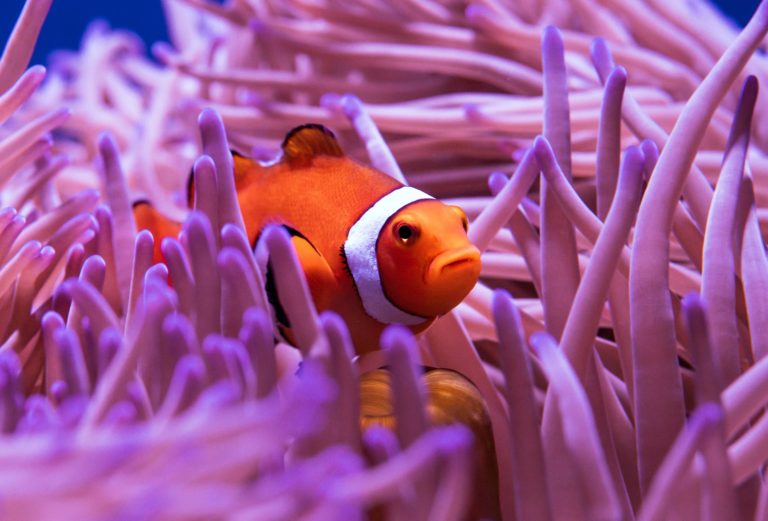

In the far north of the Great Barrier Reef, the water is the hottest and certain corals can survive the high temperatures. A multi-institute collaboration called the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program is looking into selective breeding of coral to introduce heat tolerance into populations that don’t have it.

Kate Quigley is a research scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science outside Townsville, Queensland, who studies selective breeding of corals for heat tolerance in the face of climate change, Nature reports.

Picture: Unsplash

Coral release millions of eggs and sperm into the waters every October to November during a mass spawning event. Quigley’s research brings this phenomenon indoors into a controlled environment and with selective breeding, they can introduce heat tolerance into populations that aren’t.

Coral bleaching is the phenomenon when corals are stressed, they expel photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae that they need to survive. This happens when water temperature increases, corals are under much stress and subject to mortality. Picture: National Marine Sanctuaries.

The heat-tolerant corals breed naturally with the ones farther south during spawning, but Quigley notes that this is not happening at a fast enough pace to keep up with rising sea temperatures.

The Great Barrier Reef is the size of Italy and by scaling up the seeding process and selectively breeding in land-based nurseries such as at the Australian Institute for Marine Science, breeding heat-tolerant coral can give the reef a 10-fold increase in survival.

Selective breeding can buy the reef time, but it is no silver bullet in combating the effects of climate change. Heat tolerance from natural genetic variation will run out if temperatures continue to spiral upward. Techno-fixes such as this may help mitigate the problem in the short but saving the Great Barrier Reef will involve addressing the larger problem of anthropocentric climate change.

ALSO READ