Written by Lorraine Kearney

Cape Town, the first colonial settlement in South Africa, is home to some of the oldest cultivated gardens in the country. And many of its trees are beloved for their heritage value – some simply by virtue of their history; some because they are attached to historical buildings. And some are noteworthy for their size.

And then there are the Champion Trees, proclaimed and protected under the National Forests Act 84 of 1998. They have borne witness to hundreds of years of history.

Champion trees are extraordinary single trees and groups of trees assigned “champion” status by the national Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. Champion status is assigned according to trees’ biological attributes, age or heritage significance and they are protected under section 12 of the National Forests Act 84 of 1998. You can nominate Champion Trees on the department’s website

We round up some of the oldest and most impressive.

The Treaty Tree, Woodstock

Down an inconspicuous side street in Woodstock, lined with stripped cars and rubbish, is The Treaty Tree, an ancient milkwood (Sideroxylon inerme). It is more than 500 years old and over the years has seen the coastline recede – it was on the city’s original beachfront – and the city build up around it.

It is here that Portuguese explorer Dom Francisco de Almeida and 64 of his men were killed in 1510 by a group of Khoekhoe in revenge for cattle raids and abduction.

Later, it became known as the Old Slave Tree of Woodstock. Humans were bought and sold and hanged in its shade.

Then, in 1806, following the Battle of Blaauwberg, the victorious British and the Batavian (Dutch) forces signed capitulation conditions, ceding control of the Cape to the British, their second occupation. It became known as the Treaty Tree and today is a national monument, though its upkeep could be improved.

The Money Tree, Kalk Bay

From the late 1600s to the 1850s, Kalk Bay in the city’s southern suburbs was home to a successful lime industry, but when that ended, it became a fishing village. It was under a Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) near the harbour – which came to be known as the Money Tree – that skippers paid their crew and traders bought their catch.

The traders would transport their fish, all the while blowing their fish horns, up the peninsular to Table Bay and the growing settlement of Cape Town.

Today the Money Tree is a rotting stump on the side of a busy intersection, forgotten and ignored. But what stories it could tell.

Many of these exotic species of tree were planted in Cape Town in the 1800s as they were known to withstand coastal conditions with salt-laden air and strong winds in their native habitat of Southern California – another location in the world that has the typical Mediterranean climate which we know of in Cape Town, says Clare Burgess of TreeKeepers Cape Town.

Van Riebeeck’s Hedge, Kirstenbosch

Jan van Riebeeck landed in the Cape in 1652 to set up a victualing station for ships plying the trade route between Europe and the East. In doing so, he deprived the original inhabitants, the Khoisan (made up of San hunter-gatherers and Khoikhoi nomadic pastoralists) of their traditional lands, starting a relationship of bloody skirmishes and cattle raids.

In 1660, he planted a wild almond (Brabejum stellatifolium) hedge around the perimeter of the settlement – about six miles by two miles. The tree is a member of the Protea family and grows horizontally and vertically. Its dense network of branches makes it impossible for cattle to pass.

Today, there is a remnant of Van Riebeeck’s hedge in Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden.

For many people, it marks the start of apartheid and the barriers between white and black people that culminated in the Group Areas Act of 1950.

The wild almond is a member of the Protea Family, most closely related to the Australian genus Macadamia, the Macadamia nut, according to the South African National Biodiversity Institute. Wild almond nuts contain cyanide and are poisonous unless specially treated by soaking and roasting, a technique discovered by the Khoisan people who used to eat them.

Old Slave Tree, Spin Street

A short distance from the Slave Lodge in central Cape Town, on Spin Street, lies a raised mound marking the spot of the Old Slave Tree. An estimated 100 000 people were sold into slavery under the fir tree – its exact species could not be determined.

The Slave Tree memorial on Spin Street. Picture: Wikimedia Commons.

The tree stood for hundreds of years until it was chopped down in 1916. Today it is largely forgotten, merely a raised plaque faintly bearing the words ‘On this spot stood the old slave tree’, walked over by pedestrians and passed by bustling cars.

The Company’s Garden

Spin Street got its name from De Oude Spinnery, set up by Willem Adrian van der Stel, who succeeded his father, Simon, to become governor of the Cape in 1704. He wished to start a silk industry and imported silkworm eggs and seeds for black mulberry trees (Morus nigra), on which silkworms feed.

Slave children were tasked with unravelling the silkworm cocoons. The industry failed to flourish and was soon abandoned.

Today, a gnarled black mulberry tree still grows in the nearby Company’s Garden in central Cape Town. It dates to 1800 and is probably the offspring of one planted earlier for the failed silk industry.

There are other noteworthy trees in the Gardens. A colossal Ficus elastic (rubber tree), known as the Company’s Garden Giant, stands guard at the northern entry. It is almost 27m tall.

Ficus elastic (rubber tree), known as the Company’s Garden Giant

The garden was established in the 1650s by the Dutch East India Company to provide fresh produce to ships rounding the Cape plying the trade route to the East. Hendrik Boom prepared the first ground for sowing seeds on 29 April 1652. By 1653, the garden was self-sustainable year-round.

One of the longest-lived trees in Cape Town is about 370 years old, says Burgess – the saffron pear tree (Pyrus communis) in the heart of Cape Town in the Company’s Garden. It is documented as being the oldest cultivated tree in South Africa and was brought here from the Netherlands around the time of Van Riebeek

Palm Tree Mosque

Picture: Wikimedia Commons

Tucked away in the hustle of Long Street in the city bowl, the Palm Tree Mosque (or Dadelboom Mosque) is the second oldest mosque in Cape Town, built circa 1780 – a second storey was added circa 1820. It was named after two tall palm trees at its entrance. The garden is now paved and one tree was blown over by the powerful Southeaster that roars through the city. But the other still stands, testament to the strong Islamic faith in Cape Town.

The Arderne Gardens giants

The Arderne Gardens, one of Cape Town’s most popular parks, beloved of wedding photographers, is home to several huge trees – both tall and wide.

The gardens were planted by Ralph Arderne in 1845, who collected plants from around the world for his garden, which became famous for its exotic trees. Arderne died in 1885, but his son, Henry, carried on planting up the family garden until well into the last century. Landmark trees, Champion Trees all of them, planted by the Ardernes are:

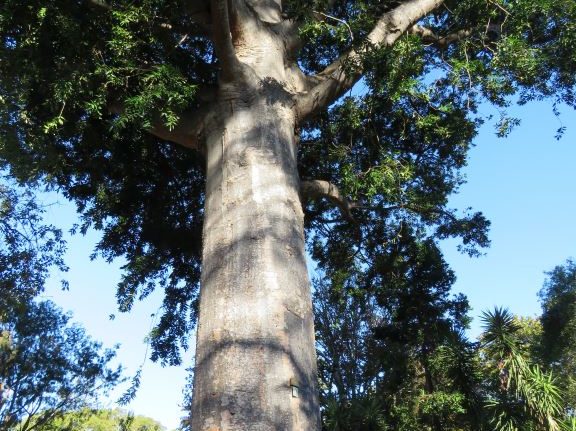

Agathis robusta (Queensland kauri).

The Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay fig), known as the Wedding Tree so popular is it as a backdrop for photographs; the Auracaria heterophylla (Norfolk Island pine), the Arderne pine; the Quercus suber (cork oak), the Arderne cork oak; the Quercus serris (Turkish oak), Arderne Turkey oak; the Agathis robusta (Queensland kauri), the Arderne kauri; and the Pinus halepensis (Aleppo pine). The Arderne Aleppo pine is quite possibly the largest in the world.

The others

There are plenty of other notable trees in Cape Town, whether Champion Trees or simply remarkable thanks to their age or size. Among them are:

Eucalyptus and a variety of other tree species in the Tokai Arboretum, where trees have been planted since 1885. It was laid out by Joseph Storr Lister at the beginning of the forestry industry and is now part of Table Mountain National Park.

The Herbert Baker chapel trees are a collection of Eucalyptus saligna (Sydney blue gum/saligna gum) standing next to a chapel designed by Sir Herbert Baker on Orpen Road.

The Table Mountain grove of Sequoia sempervirens (California redwood) was planted in 1897, forming a landmark and recreational area for residents. It includes tall Monterey pines at the fringe of this grove in Tokai plantation, part of the Table Mountain National Park.

The Kindergarten Giant, a Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay fig), is a large landmark tree on the University of Cape Town campus, loved by generations of children.

Other Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay fig) landmark trees of the same vintage as the Arderne Gardens trees (about 160 years old) line Fernwood Avenue, in Newlands.

Many know of the camphor trees of Vergelegen Estate in Somerset West, but Cape Town has its own champion Cinnamomum camphora – the Hohenort Grove of camphor trees is about 250 years old, growing behind cellars on the historic farmyard that is now the Cellars-Hohenort Hotel on Brommersvlei Road in Constantia.

The European oaks (Quercus robur) in the Company’s Garden and at Groot Constantia have borne witness to hundreds of years of history, too, and the stone pines (Pinus pinea) on Groote Schuur Estate have been looking across the bay for more than 150 years. But they are very thirsty trees and corrode indigenous flora, and they are being removed.

Examples of some of these very old public trees are the last few remaining 200-year-old Quercus robur in Newlands Avenue. Sadly, many of the original avenues of trees have already fallen or been removed due to safety concerns but a few remain, says Burgess. The City has had a proactive campaign in the last 30 years to replant new oak trees.

TreeKeepers Cape Town was established to raise awareness about the significance of old trees and promote better care and funding for their ongoing healthy existence.

Pictures: Clare Burgess

ALSO READ:

Too hot to handle: Why South Africa’s cities need more trees