Wildlife conservationist Dirk Engelbrecht went missing along the Vaal River while trying to rescue hundreds of weavers, herons and egrets whose nests were under threat from drowning due to the high water levels earlier this month.

READ: Conservationist goes missing while helping birds along Vaal River

The South African Wildlife Rehabilitation Center sent out teams after the recent torrential rains raised the level of the Vaal Dam, which had to open the sluices, endangering birds along the rivers banks.

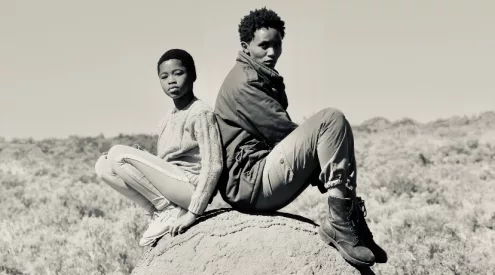

Dirk was one of the rescuers going out on 3 January and went missing. He was eventually found clinging to a tree for more than 24 hours. He recounts his harrowing experience in an interview with Getaway Magazine.

READ: Missing man found ‘clinging to a tree in raging waters’ in Vaal River

Can you describe what led to you being swept away?

As much as there were many parts of the river that were not extraordinary, there were some dynamic areas. Where I initially capsized (at about 2 PM) there were three distinct bands of water across the width of the river. I crossed the middle section to approach a cluster of trees (submerged island) and the chop was very up-and-down. I lifted at one point and capsized. By the time I got my equipment and myself onboard I had drifted just slightly toward the rapid – just enough to be handed to the draw. Like a conveyor belt, it locks you in and whips you off at a tangent.

How did you lose your kayak and what happened next?

Within seconds (of hitting the rapid) I impacted with a tree in the dense treeline to the right. I managed to roll so I didn’t directly impact the (willow) tree. The kayak hit the tree and I impacted the kayak (ribs first – it made holding on later that much more uncomfortable). After the impact, I slipped under and grabbed for branches. I grabbed willow branches under the water but with the force of the water, they just snapped. 12m downstream I grabbed hold of a tree stem. I still had the oars in one hand. I wedged the oars in this tree and then leapt across to a tree 2m away. This tree had a fork about 30cm off the water. I stood in this fork until the next morning.

Can you describe your experience in the tree?

I had a tiny wedge (maybe 10-15cm by that) to stand on. There was a snapped-off branch butt to hold on to. The trunk was vertical but it was possible to get to a 45-degree section I could likely cling to in case the water rose. Since I was standing I could not afford to sleep and I didn’t have enough fabric to reliably tether me to the tree in a standing position.

I alternated my feet and massaged my upper legs to relieve cramps. My feet went numb several times. Storms loomed violently on two occasions, which could either have directly affected the river’s level or the dam’s (requiring more sluices to be opened).

I prayed them away and they cleared as quickly as they formed. I had markers to monitor any rise in water level. After about 14 hours I started nodding off (I had just come off a 40-hour emergency shift over New Year’s and only eight hours sleep over the next 2 days). I had to keep vocalizing to stay awake. If I stopped, I would suddenly jolt myself awake.

If I entered the rapid water it would end with a high-speed pinball game with trees and jagged debris for hundreds of meters. My goal was sunrise. I could dry off, warm up and everything pointed to a first-light rescue operation. If my friends and colleagues Brendan and Danelle Murray (from Owl Rescue Centre) had not met a similar fate they would know roughly where I was.

The “trap” I was in made theirs and the NSRI rescuers’ safety my biggest concern, throughout. After first-light was delayed by unfortunate overcast and damp weather I spent 30 mins calling knowing there was a slim chance my voice would carry over the roar of the water. About 30 mins later I heard the faint drone of a watercraft. After five minutes I saw the bobbing of two red helmets blipping through the tree line. I yelled and waved and the NSRI crew’s faces swung round. They were as excited to see me as I was them.

Then after a minute of deliberation, the pilot seemed disappointed to break some bad news. They would have to leave and return with a different approach. He apologized – I smiled and waved them off. I knew it was as good as wrapped up. The crew returned and skillfully reversed, with rapid counter-steering, against 3 converging streams. They stopped a meter short and barely finished their instruction before I was met on the bank (a couple of km’s away) by about 70-80 rejoicing members of the nearly 100 people involved in the search.

What led you to become involved in conservation?

Observing how much unnecessary harm is done to nature in the urban environment, solely by humans, I needed to find a way to make up for it on behalf of my kind. Due to our dependency on nature, when I save it – I get to save us too.

Dirk works for non-profit organisation Wild Serve, who states as their mission: ‘To Sustainably Enhance Indigenous Biodiversity and Advance the Culture of Communities toward Responsible Environmental Stewardship.’

Picture: South African Wildlife Rehabilitation Center