Sun, salt, sand, and stone; prolific birdlife and the world’s second-largest wildebeest migration. To many, these are the only reasons to visit Botswana’s world-renowned pans. A frequent visitor reveals a whole lot more.

Words Grahame McLeod | Photos Grahame McLeod & Melanie van Zyl

Established in 1988, Nata Bird Sanctuary was Botswana’s first community project.

My 4×4 came to a grinding halt. I pressed down hard on the gas, but nothing happened. All four wheels were now well and truly stuck in gooey black mud. This was on a trip with members of the Botswana Bird Club at the edge of Sowa Pan to view countless bird species enjoying the waters of the recently flooded pan – pink flamingoes, huge white pelicans, avocets, spoonbills, stilts – and thanks to a length of rope and some elbow grease, the Hilux finally came free, and it was back to our binos and scopes.

READ: 5 Family Safari Lodges in South Africa for the ultimate adventure

Lekhubu Island at dawn is an enchanting spring of scraggly baobabs in a sea of salt pans.

A few years ago, we assisted Irish ornithologist Dr Graham McCulloch, who was researching the pans’ ecology and the diet and movement of flamingoes. The study revealed that flamingoes migrate to the Makgadikgadi Pans to breed from many wetlands in South Africa, Mozambique, and Walvis Bay in Namibia. The pans are considered the second-most important breeding site for flamingoes in Africa, and Sowa Pan is one of only a few sites where the lesser flamingo breeds.

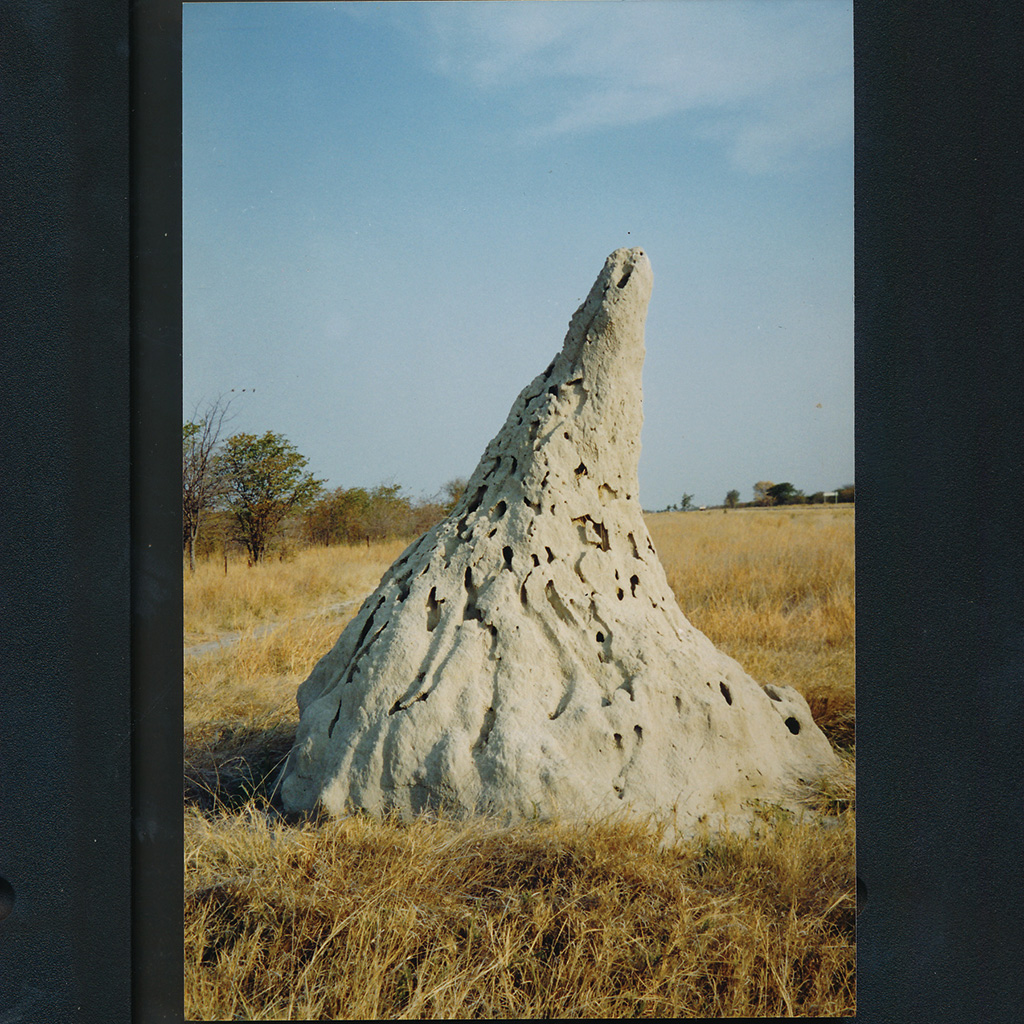

During these bird research trips, I noticed that, despite their puny size, termites punch well above their weight. Tracks weave around massive termite mounds, some a staggering five or six metres tall – the work of master builders. In the flat grasslands, these organic skyscrapers are prominent landmarks. To visitors, it may not look much alike, but to locals, they are distinctive in size, shape, and colour and are often used for navigation.

Baobabs on Lekhubu Island.

Around the pans, the apex of most mounds bends and points in a generally westerly direction – nature’s equivalent of the leaning Tower of Pisa. Countless theories abound, and one possible explanation is the need for protection from prevailing easterly winds. Other creatures around the pans devise similar strategies to protect themselves – including the white-browed sparrow weavers constructing their nests on the western side of trees. Another possible explanation is that when the afternoon sun beats down on the western side of a termite mound, the soil dries faster, shrinks, and the mound curves towards the west.

The pans usually evoke images of endless sand and grasslands stretching to the distant horizon. But I found so much more on a recent trip to the southern margin of Sowa Pan. At Moriti wa Selemo Camp in Makgaba village, off the Francistown–Orapa road, I met the camp’s South African owner, Andries Kruger. A jack-of-all-trades, he first worked as a diesel mechanic at nearby Debswana’s Letlhakane diamond mine. Later, he tested local clay deposits for their potential to make bricks and is also an avid snake catcher. Now, he runs the lodge and operates a zipline and a fleet of quad bikes for trips onto Sowa Pan.

A flamboyance of flamingoes.

Andries drove me to a spot where I noticed tree trunks lying on the ground. Closer inspection revealed they were not made of wood but of rock-hard stone. The climate was much wetter some 280 million years ago, and large forests grew here. When the trees died and collapsed, they were eventually buried by layers of sand. Silica-rich fluids moved through the sand and replaced the wood by a process known as petrification. Petrified wood takes on different colours – black shows the presence of manganese, while iron oxides give it a reddish-brown hue.

The following morning, we drove along rocky tracks to the southern shore of Sowa Pan near Mosu village, behind which an impressive escarpment looms, capped by thick layers of hard whitish calcrete. In the past, this was a line of cliffs against which the waves of the old mega-lake Makgadikgadi (that covered much of northern Botswana) once pounded and laid down rounded pebbles to form beaches. The lake dried up about 10,000 years ago, leaving a sticky, grey saline clay that makes up the pans today. On a subsequent trip to Lekhubu Island in the southwest corner of Sowa Pan, I noticed masses of whitish pebbles at the island’s highest point around the survey beacon. This told me the lake must have been at least 30 metres deep.

Bailey’s was one of the first stores ever built in Rakops.

Rain falling on the escarpment is never wasted. It drains through the underlying sandstone and emerges as fresh springs at the base. Some of these springs never dry up, such as Unikae Spring in Mosu, and dense palm groves surround the valuable water sources. The dominant species is the real fan palm, or Hyphaene petersiana, with its distinctive fan-shaped leaves and cricket ball-like fruits. But where did the seeds come from in the first place? Botanists claim that the elephant is the main agent for the long-distance dispersal of these seeds. You won’t find elephants roaming near the pans today since water is unreliable, but large herds would undoubtedly have lived here when the ancient lake existed. Today, the palms are a source of income for people. Tapping real fan palms for white sap produces a potent firewater – palm wine! The stem is cut just above ground level to collect the sap, and the sap drips into a container through a funnel attached to the stem.

The author in flooded Sowa Pan.

Outside Mosu, we walked to the top of the escarpment to explore stone-walled enclosures, up to two metres tall, and the remains of hut floors dotted with pottery fragments. Due to the semi-arid climate, few people live around the pans today, but Sowa Pan once marked the western extent of the Great Zimbabwe nation, lasting from about 1200–1450 AD. The king lived at the enormous citadel near present-day Masvingo in Zimbabwe. During this time, district governors built residences on rocky hilltops like this one near Mosu. Later, we visited a similar site by Tlapana Hill, near Mea village.

On a subsequent trip on the Nata-Kasane road, I noticed several temporary shelters along the roadside – home to an army of people, mainly women, who harvest grass in the vicinity using simple tools such as scythes. This seasonal activity is limited to winter since the grasses are actively growing and producing seed in summer. Cutting grass is big business for locals, and it’s sold to make brooms or thatch huts. The biggest buyers are lodges and guest houses, and you’ll see their trucks loading up thatch along this road.

Stone ruins on the escarpment above Sowa Pan were once dwellings for outliers from the Great Zimbabwe nation.

Two years ago, I visited Rakops village on the Boteti River, which discharges water into Ntwetwe Pan when full. It’s the usual jumble of small shops, general dealers, tuck shops, and street vendors, but, like similar villages, there are large trading stores, typically built during colonial times. One of these is R. A. Bailey’s store, established by trader Robert Bailey, who came to the Bechuanaland Protectorate in the late 19th century. Weapons, blankets, and clothes were sold to the locals in exchange for cattle. The livestock were then trekked to Palapye and transported by rail to abattoirs in the Transvaal. Some beasts faced a long trek north through the lion-infested country to Kazungula on the Zambezi. They swam across the river and were transported by rail to the Northern Rhodesian Copperbelt to feed the miners.

As a Botswana resident, my regular visits to the Makgadikgadi have shown me that it pays to get off the beaten track – it’s only by doing so that you get a true picture of a destination. If I’d not been to Mosu, I’d still think of the pans as a flat and featureless world.

The zebra is Botswana’s national animal – these grazers enjoy the grasslands that skirt Sowa Pan.

Studying flamingoes

How do you study the diet of a flying bird? Well, first, you have to catch it. This necessitated wading out into the Sowa Pan and hammering posts into the pan. Then, by means of nylon lines strung between poles and loops, we could hook their feet. Captured flamingoes were weighed, and their wings measured. We inserted plastic tubes into their stomachs to take food samples to identify the types of algae that make up their diet and compared them with the dominant algae species that occur in the pan waters. Dr Graham McCulloch also ringed the birds and attached radio transmitters to track their migration routes.

Trip Planner

Getting There

From Johannesburg, it’s about 880km on tarred roads to Nata – the gateway to the pans. The Tlokweng (near Gaborone) and Martin’s Drift border posts are the most convenient for South Africans.

Stay Here

Nata Lodge

9km from Nata is Nata Lodge, a firm favourite. It has several campsites nestled in the shade of palm trees and knobthorns, safari tents, and chalets. underonebotswanasky.com

Massive west-slanting termite mounds are major landmarks in the flat grasslands.

Maya Guest Inn

In the shade of palm trees on the Nata River in Nata is Maya Guest Inn.

Planet Baobab

Nestled in a baobab grove, 5km from Gweta, Planet Baobab has six campsites and traditional Kalanga chalets for two.

Nata Lodge.

Gweta Lodge

In the centre of Gweta, Gweta Lodge has camping and chalets.

Boteti River Camp

Boteti River Camp in Khumaga village is convenient for the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park. Eight campsites and rooms, from for two.

Moriti wa Selemo

When not flooded, you can drive onto the crusted salty Sowa Pan.

When to go

The dry winter season is cooler, and it’s easier to spot wildlife.

Need to know

During the summer rains, tracks around the pans quickly become waterlogged and impassable. A 4×4 vehicle is recommended; if possible, travel with more than one vehicle. Take everything with you – food, water and fuel.

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park: A brief history