Many years ago I heard about a mystical place, deep in the desert, where water has hewn a towering chasm into the rugged quartzites of the Oemsberg Mountains, and still trickles from the high cliff-top to land in the desert sand of a magically encircled and silent campsite. I’ve wanted to camp there ever since.

ALSO READ: 12 sensational Western Cape campsites

Desert panorama, perched on the edge of the steep drop-off overlooking the Armanshoek Valley.

Words & Photos Johann Lanz, gallo/getty images

The Oemsberg Mountains are among the most remote in South Africa. And among the driest. Port Nolloth itself is a far-flung, windswept huddle of low buildings, clinging to the inhospitable western edge of our country. But it’s still a full day’s travel from there to reach the end of the track and come within a day’s hiking distance of the Oemsberg Amphitheatre.

I’ve heard, too, of Pieter van Wyk. Pieter is a surprisingly unusual character. Born and raised in this north-western corner of the country, he is a self-taught botanist, speaker of several indigenous languages and intimately connected to this land. Pieter has three tattoos up his arm – of the three new plant species he has discovered here – and he’s keeping space for more.

Pieter van Wyk, regaling us with stories at the Venstervalle feature that gives the hike its name.

Our journey into Pieter’s world is a rare opportunity. Rare because for the last six years there has been insufficient rain to make a hiking trip into these mountains feasible. Rare because we witnessed the waterfall of the Oemsberg Amphitheatre in flow and swam in several precious, desert waters. Rare because we were met in these mountains by a wild, talkative botanist, with unusual insight into this unique botanical wonderland.

We first meet Pieter in the cobbled stone coolth on the tourist centre stoep in Sendelingsdrift. Pieter is the one wearing white wellington boots, a footwear choice that strikes me as odd for the desert. He is wiry and dark-skinned, from time in the sun. His look is half moustached konstabel, half Bedouin. Below us, the wide, lazy brown of the Orange River slides slowly by, in contrast to Pieter’s bubbling enthusiasm for where he is sending us. Pieter can’t join us as the local guide because the short-lived effects of a wetter winter make it imperative that he is out there from dawn to dusk, recording the intricacies of plant distribution across the vast and rugged mountains that form the southern boundary of the Richtersveld National Park.

The Oemsberg Amphitheatre, where Pieter was once trapped in a raging torrent during a storm.

His hike briefing is a cascade of enticing place names – Zebrawater, Koeskopfontein, Dreunbult, Gannakouriep. It includes route information and advice, the location of springs and water caches, and tidbits of interesting information. His little trail book, available from the tourist desk, collates the information in a more conventional way. Pieter will meet us in the mountains. He points to a remote slope on the map where we are likely to encounter him at the end of our second day on the trail.

The Venstervalle Hiking Trail is Pieter’s passion play – a script that unfolds in four acts over four days, and a creative masterpiece for those of us who are with an eagle-eye view of my fellow campers enclosed beneath me, and a magical, silently-echoing exploration into the almost inaccessible gorge feeding the water that falls to the amphitheatre floor, far below.

The first day’s scramble to Zebrawater, one of the springs that make hiking in this arid area possible.

The blue porthole of sky is replaced by a black one, studded with stars. Before dawn, head torches cast beams of light across the floor and walls of the amphitheatre. We will tackle Dreunbult while the early morning angle of the sun still covers it in cool shadow.

Our morning traverses high, undulating mountain valleys, recklessly decorated with flowers. These mountains are an island of higher rainfall within a desert sea of extreme aridity and are home to the richest desert flora in the world, which includes an array of very rare, endemic plant species. In the little shady thicket of trees around Modderfontein – where we lunch and fill our bottles for the afternoon’s ascent up Langbult – we find a delicate blue dove’s egg resting on the ground.

Negotiating the boulder-strewn Gannakouriep Gorge below the Amphitheatre.

To meet Pieter at Venstervalle, where we overnight, is much more than to simply meet an intense, wandering botanist in the desert. It is to really meet this place. It is to meet the tiny, rare Conophytums or Bobejaan toointjies, the strange, child-like rock art in the overhang near the falls, the taxonomic secrets of the little oasis at Koeskop-fontein, and a plant species that may still be unknown to science. It is to meet a true endemic of this place.

The beauty in plant taxonomy is mostly lost on me. I love being among the plant inhabitants of pristine landscapes. I take notice of the unusual ones. I admire the beautiful ones. But I do not need to know their lineage. I’m therefore more interested in his relationship with this land and in how he has transcended the confines of the conservative culture in which he grew up.

When Pieter talks about his grandmother, his eyes have the same sparkle they do when he talks about the plants of the mountains in which his ancestors lived. He has shown us old fields up the valley, last tilled many decades ago, a rusting plough, the ruins of the simple, impossibly remote farmhouse in which they must have eked out a harsh living. Pieter’s grandmother, he tells me, was a siener (seer). She was the member of his family with whom he most connected, and she is the inspiration for his own unusual path through life. I sense that Pieter would have talked all night if he could have, but there are tired hikers already in their beds under the stars.

Descending Reinhardt se Gat into the off-trail Armanshoek Gorge

Day three starts with a spectacular sunrise coffee spot that Pieter has organised for us along the trail. Later, at the top of a rise, before we reach God’s Window, Pieter leaves us for the urgency of new taxonomic discoveries. He uses the Nama farewell, !Gâise !gû re. Journey well.

Bababaddens, our lunch destination, is not a spring. It is a sculpted slab of smooth quartzite into which the sporadic flow of a small desert stream has patiently worn a deeply grooved chain of potholes. These are the caretakers of deep, clear pools of precious water that they somehow shelter from the powerful, desiccating forces of desert evaporation. And they are beyond wonderful to swim in on a hot day on the trail.

Expecting desert flora to be drab, you’ll be surprised by the colourful diversity – like this endemic Richtersveld pelargonium, a commonly used remedy for respiratory problems; The crimson headdress of the halfmens.

Pieter’s sense of what is adventurously possible here is probably a little above your average hiker’s. The trail map shows an optional route down the Armanshoek Gorge as ‘temporarily closed’. The route requires, among other things, finding and crawling through the narrow, hidden entrance into the dark of Reinhardt se Gat to descend a vertical section of the gorge. Unfortunately, the expense of putting in ladders thwarted Pieter’s aspirations for sharing these extraordinary places. But the bold mountaineering types in our group enjoy an exploratory side trip down the Gat and into the jumbled, vertical, quartzitic world of the Armanshoek Gorge, while the rest of our party lazes at Bababaddens.

What our next point on the journey, Panorama, lacks in terms of inspirational name, it more than makes up for in panoramic delivery, perched on the edge of the steep drop-off overlooking the wide Armanshoek Valley below. We are gratefully distracted from the steepness of the descent by a small gathering of halfmense along the path. We mingle with them, us a shabby bunch in comparison, unshaven and dirty in three-day-old hiking clothes, whereas they are like Nama churchgoers in their Sunday best. I’ve met these halfmense of the Richtersveld on other trips but I’ve never before seen them in the full flower of their crimson headdress.

By the end of the descent, our party is exhausted.

Deep shade and the gentle trickle of the waterfall welcome you into the Amphitheatre camp

A dry, dusty desert wind is gusting. Our water is all but done. Pieter has left a water cache at the veepos for which we must turn downstream but it seems an unappealing camp option, out on the windswept flats. And so we turn upstream into the gorge instead, to look for the Armanshoek Spring. We are well rewarded and replenish our water at dusk among the giant arum lilies that shelter the spring and we settle for the night in a protected spot under trees in a thicket at the edge of the dry watercourse.

Our last day is long and, because we descend to the plains below, hot. The final afternoon down the dry Gannakouriep River is much longer than we remember it from the way in. But the vagaries of memory have a pleasant surprise for us as well – a granite enclosed rock pool of deep, cool water that makes the difference between an unrelenting slog and a refreshed, inspired finish.

Vista, not Vida, for a coffee date with Pieter, high in the mountains on day three.

The forerunners of our party are out ahead. And so we arrive in the evening light to a welcoming cooler box of cold beer and a circle of comfortable camping chairs set out in the riverbed around a flaming fire, for a final, celebratory night together under desert stars.

We miss it on the way in but my wife, Sandra, and I make sure, as we exit the gates of Narnia, to kiss under the arching bough of the Shepherds Tree that crosses the path. It’s easy, with hearts full from four days of wild beauty and inspiration, to fully believe Pieter’s lore that in doing so, our love will last forever. Or if not forever, at least as long as the nearly two billion year-old Rosyntjieberg quartzite.

Trip Planner

Getting There

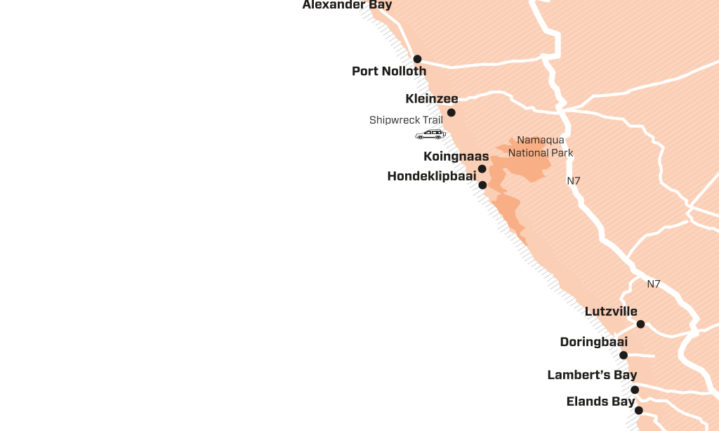

From Cape Town, up the N7 it’s a two day drive to the trail start. Overnight in Port Nolloth (many self-catering and B&B options). Arrive at the Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park office in Sendelingsdrift before midday to receive a hike briefing, before driving through the park for several hours to Hakkiesdoring Camp where the hike begins.

The welcoming deep, cool potholes of Bababaddens at midday.

About the Trail

It’s open from May to September, depending on weather and water availability. Only one group on the trail for the five-day period (four days of walking plus first night at Hakkiesdoring). R290 for the first two per day; R180 pp per day for additionals (up to a maximum of 10). R72 per day conservation fee (covered by SanParks Wild Card). sanparks.org/parks/richtersveld.

Tatasberg Wilderness Camp, one of several fine desert accommodation offerings within the park.

Stay Here

There are several highly recommended campsites and hutted accommodation options within the park, both along the Orange River and inland. Relax at one of these after the hike. sanparks.org

The comfort of stowed cooler boxes and chairs for a final, starry night in the dry Gannakouriep River course.

ALSO READ: 6 things to do in Parys, the Free State’s adventure capital