The word “˜cull’ conjures up a variety of ideas, opinions and feelings amongst many in today’s society. To some, culling is simply a method used to control animals in order for a particular outcome to be achieved, whilst others feel that is culling is immoral and inhumane.

We all know that culling is extensively used in the agricultural sector with regards to livestock and production animals. The criteria for culling these animals are mainly based on population or production factors. So in a domestic or farming situation the culling process involves selection and the selling of surplus stock. The selection may be done to improve breeding stock or simply to control the group’s population for the benefit of the environment and other species.

In the poultry industry, male chicks are culled shortly after hatching as they do not lay eggs and hence serve no purpose when they have grown into roosters. To the general meat and dairy-product eater, this is deemed “˜natural’ and “˜simply as God intended it to be’. Let’s face it; a braai would not be complete without a few tender chicken breasts and a large juicy rump steak.

On the other side of the spectrum, the culling of wildlife in recent years has created great uproar in the public sphere. Culling for population control is a commonality in wildlife management, particularly on African game farms and in Australian national parks. With regards to the great majestic beasts of the African plains, elephants are often the targets of the culling process due to their abilities of destruction and harm against other elephants, wildlife and humans. Elephants are also notorious for destroying trees and the general habitat, which becomes a major problem for wildlife sanctuaries and reserves.

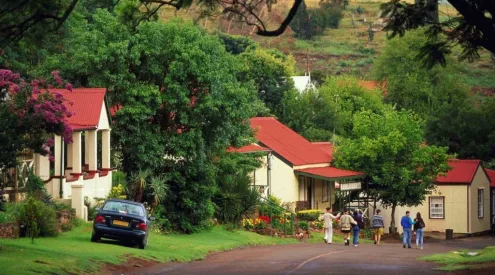

With regards to Kruger National Park, its history of elephant population management began as an ecological movement during the late forties, fifties, and early sixties in order to establish a balance amongst elephant numbers and to also preserve other species and the environment. If one reads Bruce Bryden’s book “˜A Game Ranger Remembers’, you will learn that culling was all in a day’s work for the Kruger rangers.

Culling was a constitutional part of official park policy from 1964 to 1994. During this time, elephant populations within the Park maintained an average of between 6000 and 8500. Since the culling ban in 1995, the elephants in Kruger have grown more than 5,000 in number which has sparked talk and debate amongst naturalists and environmentalists. The number of elephant populations has swelled over the years and it has been documented that this number increases at an average rate of around 7% per year.

According to South African National Parks chief executive Dr. David Mabunda, the current standpoint on culling in Kruger is that no mass culling of elephants will take place any time soon as Mabunda describes it as a “heartless, impossible and unaffordable” idea. However, he has further stated that SANParks will need to cull animals in the future in order to control their numbers and preserve the park for future generations. When this decision rears its ugly face it will “be informed by scientific research, management imperatives and prevalent trends as an option of last resort.”

Apart from elephant culling, a variety of solutions have been put forward and are being utilised such as contraceptives for female elephants, translocation of elephants to other areas, eradication of artificial supplies that help elephant populations survive in negative natural circumstances, and the establishment of paths and removal of fences for elephants to roam to other areas.

What are your opinions on animal culling? Whether it be the culling of farm chickens and cows or the culling of elephants and buffaloes? Post your comments below.