I remember my first scuba dive in iSimangaliso, looking at the underwater world through the lens of a traditional healer, who’d dreamed of it and seen it in visions, and as someone who’d used the beach for recreational purposes – neither of whom had ventured beneath the surface.

Picture: Mnqobi Zuma

I’d thought the waves were as beautiful as the ocean could get. You hear stories about what it’s like underwater, but it was another thing to see it. It was bursting with colour, shades I’d never seen on land. I wanted to touch everything, even though you’re not supposed to.

And feeling weightless, which many people describe as encompassing, but I’d go as far as to say it’s like being inside a womb. Relinquishing control, moving with the water, not against it, is beautiful.

It wasn’t lost on me that what I saw in that Marine Protected Area (MPA) was there because of measures to keep it pristine. That’s when I started to appreciate the importance of protecting the ocean and wanted to act as a voice for those corals that might not be able to come ashore and be like, you need us!

I’ve always loved nature. I grew up in Durban with the beach on my doorstep and, as a child, would visit rural areas with my family. I’m also a traditional healer, identifying as a sangoma. As I rely on natural remedies to treat ailments, I feel it’s my responsibility to preserve the natural environment.

Traditional healers are spiritually connected to water and gain knowledge and gifts of healing from its spirits. But according to folklore and mythology, it’s not a good idea for them to be near bodies of water, and you read reports of drownings when people go for cleansings.

But if those stories are true, every time a traditional healer wades into water, the spirits are so overcome with emotion that they take them. I thought, how can I break this stereotype?

It’s easy to misunderstand traditional healers and their use of natural resources because their community is not well represented. Likewise, it’s hard for traditional healers to see other people beyond those who closed doors and partitioned areas.

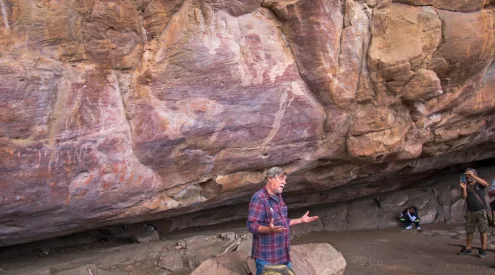

I studied journalism and became an environmental journalist, then a science communicator, so I’m a product of ancestral communication and science. I see storytelling as an opportunity to bridge both worlds.

ALSO READ: SA wildlife filmmaker scoops award for African vultures documentary

Two years ago, Nature, Environment & Wildlife Filmmakers (NEWF) invited me to join a fellowship of 10 black and brown women from the African continent, a mixture of storytellers and scientists. We trained as dive masters, but also learnt how to use an underwater camera because ocean-facing communities are more likely to connect with a story than scientific jargon.

Picture: Steve Benjamin

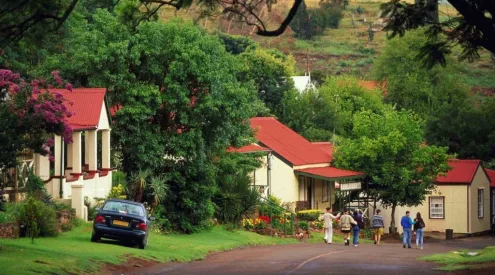

I work for the WildTrust, an NGO that aims to pursue a ‘thriving and resilient world’ through two core programmes: WildLands and WildOceans. I am part of the communications team for the WildOceans programme. The organisation partnered with the I Am Water Foundation to provide the children of Northern Zululand in the iSimangaliso MPA with two-day immersive experiences, exploring rocky shorelines, learning ocean literacy and overcoming their fear of the ocean.

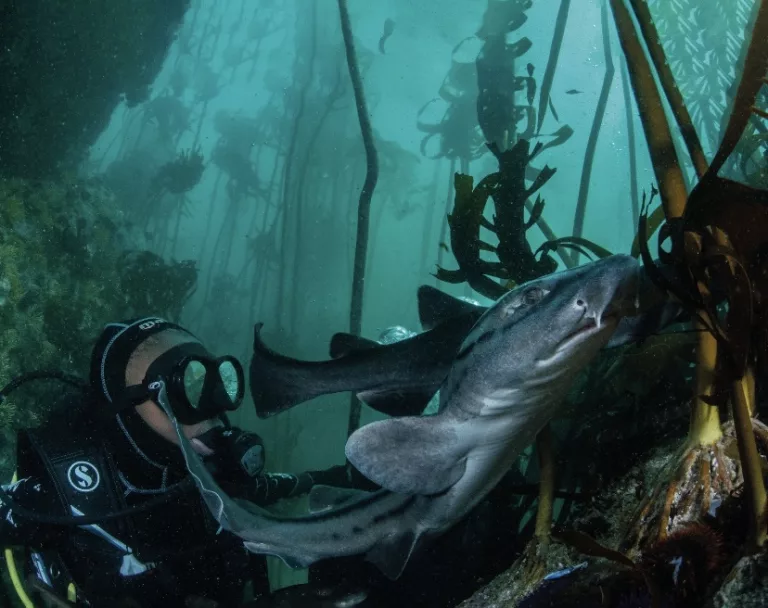

I was recently involved in the short film See Us, part of the organisation’s marine campaign On the Brink, which highlights South Africa’s ideal position as a lifeboat for shark and ray species in its waters and globally. Cinematographer Steve Benjamin and I take viewers along the coastlines of two MPAs, Aliwal Shoal in KwaZulu-Natal and Table Mountain National Park in Cape Town. I was adamant that as much as hero shots are beautiful, I wanted children from my community to see someone who’s like them and believe following in my footsteps is obtainable.

I had underestimated how big blacktip sharks would be. I’m 45kg, so most things are bigger than me, but some were triple my size, great slabs of muscle. I used my prior diving experience to remain poised and not act super-jittery in the presence of these lions of the ocean. Surprisingly, they were like puppies. I don’t think they realise how big they are. And despite being curious, they’re also shy.

Picture: Steve Benjamin

We didn’t see all the species we’d hoped for and had to admit this is potentially the future of our underwater world. I hope the communities that watch See Us will learn about the ocean’s connections to climate, drought and rain, and how it affects them. The On the Brink Campaign highlights how sharks and rays are either on the brink of extinction or expansion, and ultimately, the choice is ours. Perhaps this film will inspire them to protect our water.

This article was written by Lisa Abdellah for Getaway’s November 2023 print edition. Find us on shelves for more!

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: South Africa’s succulent smuggling crisis worsens