Is there a piece of culinary equipment more South African than the humble but revered black pot? Nothing says ‘South African food’ better than a three-legged, cast iron pot hovering over a heap of glowing coals, writes Louzel Lombard Steyn.

Words: Louzel Lombard Steyn | Photography: Alamy, Supplied

Can you really call yourself a South African if you haven’t indulged in the magic of the potjie pot?

My version of playing house-house as a kid on the farm involved packing out a flat brick blueprint of a house on a patch of clean-swept dirt, and calling it my poppehuisie (doll house). It was elementary but it had a kitchen section where my farm friends and I would make a real fire and cook real food in my beloved three-legged black pot.

I insisted on this Size 0.5 Best Duty black belly pot for my fifth birthday and, looking back now, it was the best gift I have ever nagged for. Its maximum volume is only about three cups, but my friends and I used every inch of her little black belly to cook up anything ostensibly edible. Some of the favourites included Imana mince (stolen from our parents’ pantries or the farm stoor [store]) and cabbage stew, freshly caught pigeon, and our favourite: self-harvested morogo, or wild greens, with maize meal. My mom always politely declined a helping of our morogo, probably because we were actually cooking plain old weeds. I wasn’t deterred. For us, that thistle stew was the food of the gods.

Over the past 25 years, the mini black pot and I have developed together. Her cast iron belly is now well-seasoned and I no longer cook those, um, interesting thistle concoctions. Phew. South Africans love their big-bellied, three-legged potjies. We’re weaved on the warm bowls of umphokoqo, or maize meal, they produce. However, while the use of a large, sturdy pot over an open fire is deeply rooted in African culture, cast iron cookware was first brought to the continent from Europe in the 17th century with the early colonists. There, the three-legged pots were associated with witches and druids and the cooking of all sorts of nasty potions.

Understandably, it didn’t really take off on the culinary scene. Nowadays, modern potjies are called ‘dutch ovens’ overseas, thick-walled but flat-bottomed pots with tightfitting lids that are made of cast iron.

You’d be best advised to make a booking for Sakhumzi as the venue fills up quickly.

South Africans prefer the big bellies to the flat-bottoms. And here, the three legs have nothing to do with witchery (though, they do have a certain kind of magic in them). The long legs allow for a big fire with flames or coals to go underneath – a sought-after trademark for South Africans and our obsessive love of cooking with fire.

A good potjie can transform even the humblest of ingredients. Think of traditional potjiekos, or fresh ujeqe or dombolo (steamed bread) or a bowl of mushy, smokey umngqusho (samp and beans) that has been simmering over the coals for hours. These recipes all live and breathe and have their being in the trusted black pot, and gain their unique flavour from a combination of cast iron and smoke.

Yes, you can taste the pot. A salesman of the now-defunct, Durban-based Falkirk black pot company once noted that the pots had ‘health benefits’ because of the iron that was transferred from the pot to the food. Excess iron can be a bad thing, I know. But for poorer communities – and for scrawny children especially – an extra iron kick in a bowl of breakfast porridge is just what the doctor ordered.

Potjiekos – as in the dish made in the potjie – also originated as a poor man’s meal. It came from the Netherlands and Spain, where communities gathered to cook and share food during wartime. Anything edible would be layered and stewed together over low heat with lots of liquid to produce a thick broth that could feed many. If available, hunted meat would be added. The dish has transformed somewhat in modern times; these rich South African stews are anything but a wartime meal. However, many still hold true to the tradition of cooking it in layers and – most importantly – never stirring or mushing the ingredients together.

If choice is your thing, Boesmanland Plaaskombuis has your potjie love covered.

The most important attribute of a potjie, however, has nothing to do with method nor stirring madness. It’s not the flames nor the fire, not even the secret iron oomph. A potjie’s truest quality is that it is designed to feed the people. Lots of people. In a war camp, in a village, or heck, even in a humble makeshift poppehuisie with your bestest friends around the fire.

Soweto flavour

Back in 2001, Sakhumzi was the only eatery in Soweto’s now-famous Vilakazi Street. A lot has since changed but fantastic African food and a communal festive spirit remain at the heart of this restaurant-cum-shebeen.

Weekends are a vibe at Sakhumzi’s, but the Mogodu Monday buffet will blow your socks off. The legendary buffet consists of stewed tripe and trotters, chicken feet (aka runaways), pap, umngqusho, steamed bread (dombolo) and chakalaka. It’s an all-you-can-eat spectacle of proudly South African cuisine all for R205 per person (excluding drinks). Booking is advised. 011 536 1379

Where: Sakhumzi Restaurant, Vilakazi Street, Orlando West, Gauteng

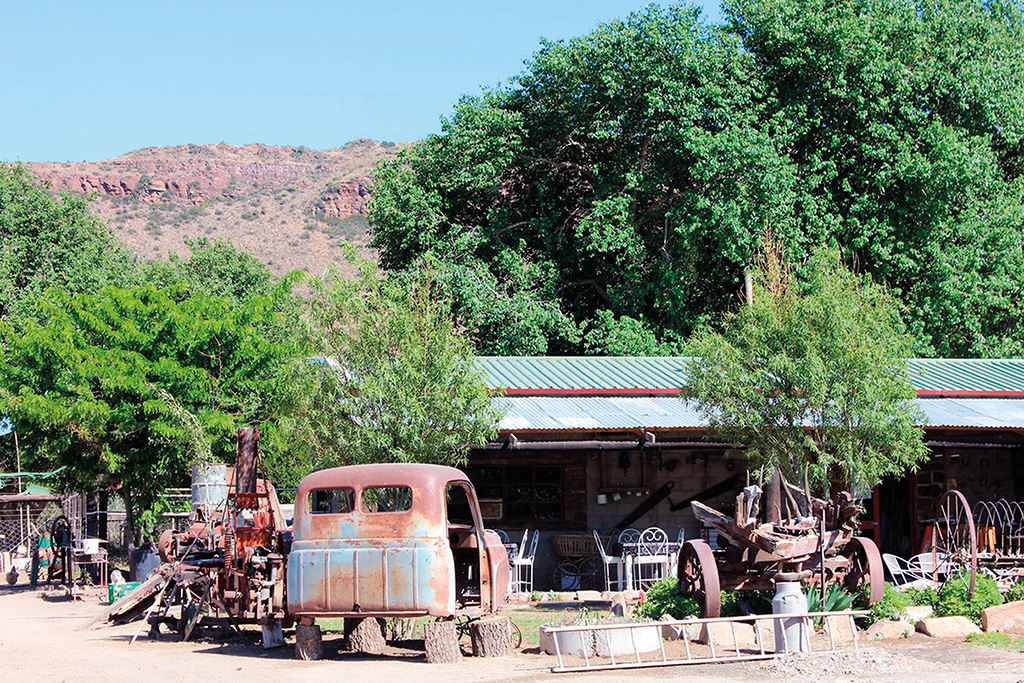

Tot Hier Toe padstal boasts the use of Karoo meat in their potjie offerings. Lamb is a firm favourite with patrons.

Pot on tap

Set on a beach in the seaside town of Langebaan on the West Coast, Boesmanland Plaaskombuis captures South Africa’s love of communal food and eating. Wooden stumps serve as seats around round tables overlooking the lagoon. ‘Proudly African Boerekos’ including a minimum of three types of potjiekos, are always on the menu and all the other dishes of the buffet are prepared on open fires in big black pots. Owner Lindes Basson swears by his humongous black pots. ‘We’ve had them since the start of the restaurant 21 years ago, and they’re still working as hard as the day we first got them,’ he says.

The extensive eat-as-much-as-you-like menu offers 24 individual dishes and desserts. A cornerstone classic is the restaurant’s famous fish potjie, made with the freshest bounty from the rich West Coast waters. At R197 a head for adults, it’s a steal.

082 773 0646

Where: Boesmanland Plaaskombuis, Langebaan, Western Cape

Karoo stew

Few places are better-suited to potjiekos than the icy Karoo. That’s why Riel Malan and Chrissie Swarts from Tot Hier Toe Padstal just outside Nieu-Bethesda always have a potijie or two (or three) cooking on the fire. ‘Our lamb pot is the favourite,’ Chrissie says, ‘because we use only the best meat from right here in the Karoo. That makes all the difference.’ Other classic potjiekos meals include traditional tripe, served with samp and freshly baked bread, as well as the more modern biltong potjie.

082 579 7460

Where: Tot Hier Toe Padstal, 501 Martin Street, Nieu-Bethesda, Eastern Cape

Fancy some potjie but feeling a bit lazy? Order from Kwethukuhle Restaurant via Uber Eats.

Order in

Who says you can’t have delicious, homemade African cuisine on demand? Pinetown’s famous Kwethukuhle Restaurant has recently gone online with Uber Eats, which means fans can enjoy its traditional tripe with steamed ujeqe at home, without the effort of cooking it. Steamed bread is made by placing a baking tin filled with dough inside a black pot that’s half-filled with water. Keeping the lid on, the dough rises as it steams, forming a thin, sticky layer instead of a crust.

If you’re feeling adventurous, why not order the inhloko, or cow’s head stew, with your delicious steamed bread? Note, however, that this is traditionally only enjoyed by men, as the heads of the household. 083 594 9001

Where: Kwethukuhle Restaurant, 138 Mariannridge Drive, Caversham Glen, Pinetown, KZN