By Warren Ngobeni

Wildlife photography isn’t an easy career for anyone. But for a young black person, like me, it’s a mountain to climb. It’s an area that’s mostly ruled by white people, and my community is very poor.

I live in a small rural community in Mpumulanga, South Africa, bordering Kruger National Park. As a teenager, I had to skip school most days to sell sweets and snacks in the local market to make money to buy food for my family. My mother worked away from home, my siblings were not around, and I was brought up by my grandmother who was sick. My grandmother and I used to watch wildlife programmes on the TV together, and we would talk about every animal that we saw. Those are the moments that inspired me and made me want to become a wildlife photographer. I dreamed of one day holding a camera, taking pictures and telling stories to help conserve nature.

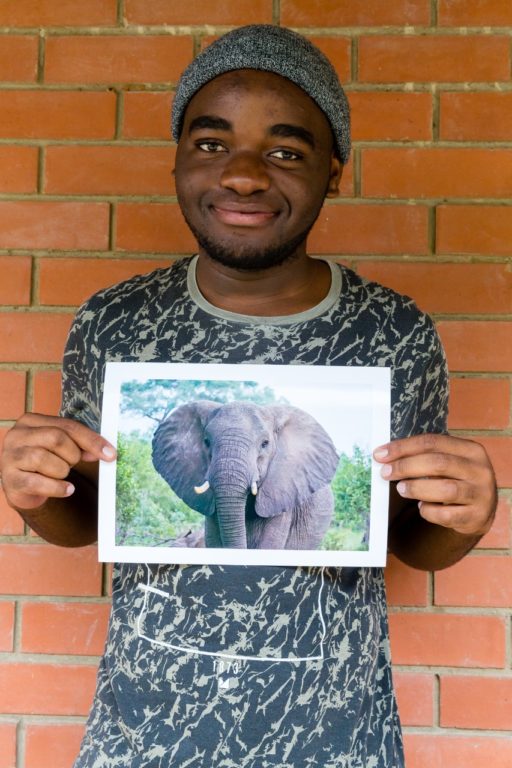

Warren Ngobeni

But that dream will be difficult to achieve. The photographic industry is white-dominated, and there are reasons why it’s like that. Here in South Africa, apartheid shaped the world we live in now. White people have more land than black people, and that helped them to own, manage or work in game reserves and lodges. Access to the reserves is difficult and, for someone like me, it requires transport, fuel and equipment, which is expensive. Growing up, the priority was having enough food on the table. It was impossible for me to go to a game reserve and see wildlife. I didn’t know anyone working in the safari industry or anyone like me who loved nature.

Although South Africa’s experience with apartheid was unique, many black people across Africa face similar situations of not having access to national parks and reserves, or access to equipment, or opportunities to develop skills and work in photography or conservation.

We come from very poor places where we are told that dreams are not for people like us. There is no one to encourage us even if we do think of becoming a vet, a wildlife photographer or working in conservation.

Warren Ngobeni

How can we get more black people into wildlife photography? We need more role models, more opportunities, more exposure to our wild places and wild lands. There are still so few black people working in conservation, so few Africans featured in wildlife TV programmes, and so few opportunities to access and engage with our natural history and heritage. The solution starts with the people who are leading the way now, for them to encourage, support and mentor young black people and help them become role models.

There are many white people photographing Africa’s wildlife, both locally and internationally. How can they help us? Can they offer to take black people into a game reserve, come to our schools to give talks, help mentor a keen young person, or donate second-hand equipment? Photographers and travellers can ask their guide or tour agent how they can help next time they’re on safari. I’m a graduate of the Wild Shots Outreach programme, which supports young Africans in accessing our wildlife heritage and developing employment skills through photography, and I believe we need more programs like this, operating in other parts of Africa.

We also need more women in wildlife photography and conservation. But talking to my female friends, they have no knowledge about what goes on in wildlife. They have no idol to look up to, to give them that belief that they can make it in this industry. Most photographers are males. Young women need to be more confident in asking questions and thinking they can do this. Having more females in the industry would have a big impact. Women are often so good at storytelling and relating to people and different cultures.

We need more ways to help black people access their natural heritage. If that happens, I believe it will deliver real results and our wilderness areas would be safer and healthier. We must teach children at a very tender age that the world we live in should be conserved.

Right now, we have animals being poached and hunted for bushmeat, trees are being cut down for firewood, and our water is contaminated. White and black people should work together to help fight the problems we face. I don’t just want people to see pictures of what wildlife we used to have, as a result of our actions or lack of knowledge.

Warren Ngobeni in action, left of frame

I’ll never forget my first photo assignment. I went with Wild Shots to document a rhino dehorning operation last year. This was one of the most emotional experiences in my life. When the horn was being removed, I felt my hair stand up on my neck. We were taking away this animal’s beauty and something that makes this animal unique to try and save it from being poached. In my head, I kept repeating the words “You’ll be safe now.”

When I capture images like this, I want the message to be obvious: we can’t let these iconic animals go extinct. I want people to see what’s being done to try and save these animals. I’m very proud that one of my images made the front pages of South Africa’s national newspapers.

For me, as a 22-year-old, I’m happy with where I’m heading. I’m on the long road to becoming a photographer and to being known in my community for my work. I’ll find ways to tell my stories and hopefully make a difference. My stories are for everyone, from every corner of the earth, to show that we need to conserve our world. I’m learning to grab every opportunity and to work hard. I want to inspire more black people like me. If I can make it, then it will give other people hope.

Wild Shots Outreach (www.wildshotsoutreach.org) is a South African NGO working in the Kruger area that supports young Africans from disadvantaged communities in accessing their wildlife heritage and developing employment skills through photography. Warren joined a Wild Shots Outreach course in 2020 and has since completed various photographic assignments, despite never having used a camera before or had the chance to visit a game reserve. He now works as an assistant tutor for Wild Shots Outreach, teaching wildlife photography and inspiring the next generation of African conservationists and photographers.

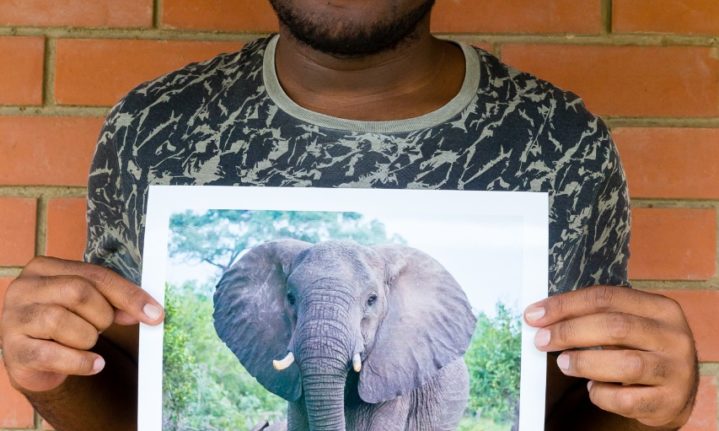

Here is some of Warren’s work:

There’s an easy way to tell the African elephants apart from their Asian cousins – their ears! African elephants have…

Posted by Warren Rrenzo Ngobeni on Wednesday, 24 March 2021

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Picture: Warren Ngobeni