‘The project is aimed at rectifying a tragic mistake made over a hundred years ago through greed and short-sightedness. It is hoped that if this revival is successful, in due course herds showing the phenotype of the original quagga will again roam the plains of the Karoo.’

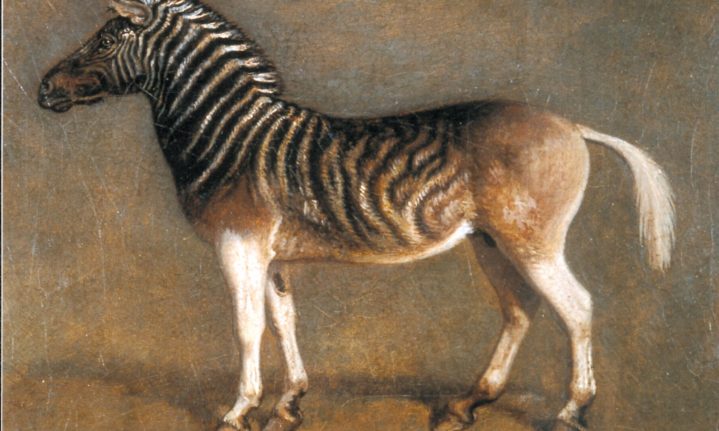

Portrait by Samuel Daniell, circa 1799.

Ever thought up a plan to bring an animal back from the dead? You’d probably say that’s madness. And even if you could, you’d receive widespread scepticism from critics influenced by tales of Frankenstein and the story of Prometheus.

But what if the resurrected beast was just a peculiar zebra and the “mad scientist” not some nefarious villain, but a taxidermist who felt the ruthless extermination of the quagga was a tragedy.

What follows is the story of one person’s determination to rectify this mistake; it would culminate in the most fascinating and ambitious breeding project, which may bring an iconic and distinctively South African animal back from ‘extinction’.

The quagga

The quagga is a peculiar-looking zebra that once roamed the plains of the Great Karoo in the thousands. Most scientists did not consider it a zebra, but another species in the Equidae (horse) family.

But, the quagga was proven to not be a distinct species, but a subpopulation of the plains zebra a hundred years after its extinction. This breakthrough can be attributed to the determination and a lifetime of work by one taxidermist to prove his initial assumption. And even then, he needed some luck.

Reinhold Rau worked tirelessly on preserved quagga specimens throughout his professional life, convinced that the quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra, but his conviction went against the consensus of most of the scientific community.

The quagga once roamed vast plains of the Karoo, where grazing pastures were far on few in-between, and competitors were ruthlessly hunted to extinction in the wild. The last captive quagga died at the Artis Magistra Zoo in Amsterdam in 1883.

‘Someone ought to do right’

Rau moved to South Africa from Germany in 1951 as one of seven taxidermists to mount mammals and birds for the natural history museum in Cape Town. A poorly mounted quagga foal tucked away among the other animals caught his eye.

Rheinhold Rau mounting a quagga foal.

Rau seemed to have an intuitive feeling that the extinction of this species was an injustice. ‘Rau seemed to have a sense that this was wrong before it was considered the norm,’ said March Turnbull, the coordinator of the Quagga Project.

He remounted that poorly stuffed quagga in 1959, along with critically examining 21 of the 23 quagga mounts remaining in the world.

Rau wasn’t just an outsider at the time for his perspective on the quagga’s extinction as a great tragedy, but he believed that the quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra found throughout the continent.

‘You should understand, that a lot of the Anglophone scientific community was influenced by morphology; how the animal looked like,’ March iterated. ‘And so they thought because the animal is markedly different from the other zebras, it must be a different species.’

Rau, with his German background, was less convinced by this morphological conclusion. But, when March recounted a story from Rau’s childhood, his persistence made a bit more sense.

In the 1930s, when Rau was growing up near Frankfurt, he went to a circus where an animal called an auroch was being paraded. The auroch, a bull that was widely spread in Europe, became extinct in the 17th century.

The Heck brothers, Lutz and Hein, claimed to have brought back the mighty auroch by breeding Spanish fighting cattle with longhorns, with other cattle breeds. This bull was physically similar to the auroch, but was genetically different and therefore a different species.

Rau with the quagga foal he remounted at the Cape Town Museum.

Regardless of that, this bull would influence Rau’s thinking on the quagga, along with a book called published by Lutz Heck in 1955 called Grosswild im Etoshaland, which suggested that careful breeding with the plains zebra could produce an animal identical to the quagga. But Lutz Heck was still looking at the quagga as a distinct species.

A species that never was

Rau was still researching in the 1980s and came across an article by RG Higuchi at the University of California who was working with sequencing this new thing called DNA, which would prompt Rau to try and make contact with him.

Rau remained convinced that the quagga was a subpopulation of the plains zebra. He would regularly lay quagga and plains zebra hides alongside each other for comparison.

Via Oliver Ryder, a geneticist at San Diego Zoo who was interested in the project and shared some of Rau’s assumptions, Rau made contact with Higuchi. He responded, telling Rau that if he had a sample, he could give it a go. Fortunately, Rau had a sample collected from a 140-year-old quagga he remounted at the Natural History Museum of Mainz, Germany, which he had kept for more than 10 years in a petri-dish.

Rau posted this petri-dish to Higuchi, who extracted DNA from the preserved piece of dried muscle and reconnective tissue. From this, Higuchi’s team was able to sequence the mitochondrial DNA, which is only transferred from mother to child. With this, they could then trace the maternal ancestry of the quagga, and compare it to that of the plains zebra.

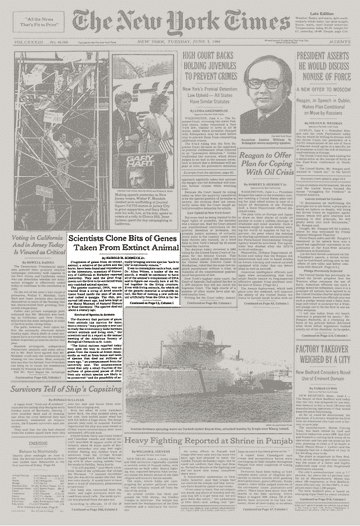

Their findings would prove Rau’s initial assumptions and the results of this study were published in a renowned scientific journal, Nature. Remarkably, this was the first time that a clonable DNA sequence was recovered from the remains of extinct species. This achievement preceded and contributed to the use of DNA to answer paternal questions and forensic investigations.

The successful sequencing of the quagga’s DNA appeared on the cover of the New York Times on 5 June 1984.

This breakthrough made headlines globally, and even into popular culture – The 1990 novel, Jurassic Park, refers to the successful recovery of quagga DNA as inspiring scientists to convince board members to pursue cloning dinosaur DNA.

Just one thing was left to do, bring the quagga back to life, and hopefully one day, the plains of the Karoo.

Look out for: Part II: 35 years on – The Quagga Project today

Pictures: The Quagga Project