Nearly a hundred years after the first visitors arrived in the Kruger by rail, a new luxury train suspended above the Sabie River, and a railway-inspired restaurant precinct, pays homage to those early patrons.

Words & Photos Lauren Dold

The Shalati Train on the Bridge took more than a year to complete, with each of the 12 carriages being fitted individually with luxury amenities before being transported one at a time to the Kruger Park.

I rolled through Kruger’s Orpen Gate in late spring, under a cloud on the brink of bursting with the first good rains of the season. The promising signs of summer were everywhere. The tree wisterias hung heavy with purple flowers, the schotias bloomed red and tiny blades of grass pushed hopefully up through the earth.

I had 140-odd kilometres to go, first east towards Satara, then south down to Skukuza. All this time the clouds grew darker, finally bursting as I crossed the Sabie River. The veld soaked up the early rains gratefully and afterwards, the cicadas emerged in full chirp, signalling the start of summer in the Lowveld.

In Skukuza, the energy was much the same, as an exciting new project prepared to open its doors. The Kruger Station and Kruger Shalati Train on a Bridge have been in the works since 2016, and are finally now welcoming guests in late 2020.

Kruger Shalati is a first-of-its-kind, five-star train hotel, which will be permanently parked on the Selati Bridge, stretching over the Sabie River. The first guests are set to board the train mid-month, just under 100 years since the first visitors to Kruger disembarked into the park.

Restaurant 3638 serves up gourmet food as well as familiar favourites, with plans to introduce unusual local fare, including crocodile, when international tourists return.

The Kruger Station, a food and entertainment hub situated in Skukuza rest camp, welcomed its first visitors during a phased opening from August to September, with the main restaurant opening to an excited crowd on Heritage Day.

The precinct sits on an elevated platform deck at treetop level, offering lovely opportunities for birdwatching. The old steam locomotive number 3638, after which the main restaurant is named, is parked proudly in the station, as it has been ever since 1979.

The place is abuzz at all hours of the day. Comprising a bar, a cafe, a deli and an upmarket restaurant, the station caters (literally) for every kind of Kruger visitor. I sat down with Chef Andrew Atkinson – of SA Masterchef fame – between his breakfast and lunch services.

A flip through the menu revealed a delicious selection of meals, with a distinctly South African flair. ‘I want to serve high quality, but unpretentious food, and serve it in a relaxed setting,’ Andrew told me.

Steam Locomotive number 3638 was built in 1949. In 2005, a Kruger Park spokes-person said the original driver of the train still occasionally visited his former ‘office’ to give it a polish.

Chef Andrew, noticing that I lingered on the dessert page, disappeared into his kitchen. He returned a moment later with a box of smore-inspired brownies. I listened while I savoured them, as he told me about his newest venture.

‘I’ve worked at the Hilton, the Hyatt, the Micheleangelo but I was ready for a challenge. How often do you get a chance like this, a blank canvas that’s yours to design?’

The Kruger Station employs and trains people from local communities and sources everything locally. ‘There is such a great selection of fresh produce in this region so I try to keep the carbon footprint as minimal as possible,’ said Andrew.

The station is also designed with children in mind, as concession manager Judiet Barnes told me over coffee. ‘I know my kids get restless in the car between camp visits, so this is a place I can let them run free and have a good time.’

The Sabie River is 230km long, and one of the most biologically diverse river systems in South Africa, home to 46 species of fish.

Within the precinct is a 360-degree cinema, which will play films and documentaries about wildlife and conservation, and the history of Kruger. The theatre seats 30, and is fitted with swivel chairs in the centre, allowing visitors to whizz round with the immersive wraparound screen.

While nostalgic touches appear everywhere, modern features do, too, and I found myself straining to hear any bird calls beyond the pop music that plays throughout the station.

At Skukuza, kudu bobotie pizzas and duck ragu have replaced the old fashioned pie, gravy and chips of vintage Kruger, and 360-degree theatres have pushed out the projector screened outdoor films of evenings past. One thing that’s remained is the tradition of an evening drink. The Round-in-Nine bar at the Kruger Station serves up cold cocktails and craft beer. ‘It’s a place for people to have a sundowner after their afternoon drive, before returning to their bungalows to light their braai fires,’ explained Judiet.

The bar borrows its name from the first train tours that operated through Kruger in the early 1920s. Entering just north of Skukuza, and exiting near Crocodile Bridge, a nine-day tour of the Lowveld by train included a stopover on the Sabie Bridge, where passengers would disembark to spend the evening on the banks of the river. James Stevenson-Hamilton, first warden of what was then called Sabie Game Reserve, would regale guests with tales of the reserve he had fought so hard to protect at the turn of the century. A bonfire, a banquet and a grand piano would complete the evening, whereafter guests would return to their carriages to sleep.

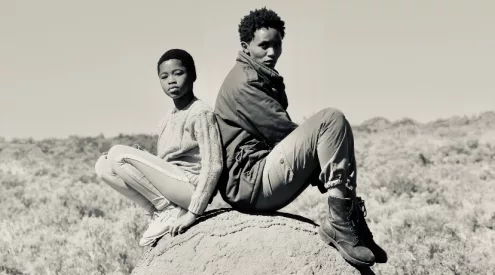

The carriage rooms were designed in collaboration with local designers, artists and craftsmen, and finished with organic textures and patterns.

But life along the Selati line was not always so rosy.

Slow down for plodders

Be mindful when driving Kruger’s roads in the rainy season. Tortoises drink from puddles on the road, often crossing slowly, so are in danger of getting run over.

Skulduggery on the Selati Line

The building of the Selati line began in 1892, as it was needed to transport gold from the Selati goldfields on the Murchison Range to Komatipoort, then on to the port in Lorenzo Marques (Maputo). The concession to build the line was awarded to Baron Eugene Oppenheim and his brother, Baron Robert Oppenheim, French entrepreneurs (and general skelms) who had dubious intentions from the start.

The Kruger Station is open all day and seats over 100 people and also provides takeaway meals for game drives.

They established the Selati Railway Company in 1892, a shareholding enterprise floated in Brussels. And secured the contract chiefly by means of thousands of pounds worth of bribery, happily accepted by the Transvaal government and the Volksraad. The construction of the line was then contracted out to the British company of Westwood & Winby, who completed the first 80km of track to the Sabie River (what is now Skukuza) in 1894.

In the meantime, the Oppenheim brothers were cooking books, cashing in false expense claims, arbitrarily hiring subcontractors and generally attempting to disguise their financial misconduct. This bewildering obfuscation could not go on forever, and in 1895, the brothers Oppenheim were found out, and the Selati line scandal bust wide open. They were charged and found guilty by the Belgian criminal courts, and sentenced to jail time. President Paul Kruger himself appeared before Belgian court, and reportedly said he saw no harm in everyone receiving payment, ‘so long as it does not amount to bribery.’

It was revealed that over one million pounds lined the greedy pockets of crooked politicians and businessmen. The implicated members of the Volksraad got off scot free, but were left with 120km of useless track. Tools were downed all along the railway, and remained rusting in the veld for 15-odd years before construction was picked up again in 1909. The rest of the line from Sabie Bridge to Tzaneen would only be completed in 1912, by Pauling & Co.

During this time, James Stevenson-Hamilton had been appointed first warden of the Sabie Game Reserve, declared in 1898.

Kruger Shalati may be shaped like a train but is fitted with all the bells and whistles of a regular five-star hotel, including air conditioning.

The first Round-in-Nine tour rolled through Sabie Game Reserve in 1923. Stevenson-Hamilton, upon seeing the itinerary, suggested that instead of ploughing through the park in darkness, the train should park on the bridge where guests could disembark and view game in daylight. This was to become the most popular stop on the trip, giving support to the campaign to decree the reserve a national park.

The Kruger National Park, almost as we know it today, was proclaimed in 1926.

Relics of this bygone era remained at Skukuza long after the line was lifted. Tracks on either side of the bridge are still in place for a short distance, leading to the steam locomotive parked in the station. In the 1980s, Selati Station Grillhouse opened up, which comprised three different carriages, two of which burned in a fire in 1995. The surviving wood-panelled lounge car, which has recently been refurbished, seats 16 and is be available for private parties.

The most spectacular nod to this glamorous era of travel however, is the Kruger Shalati Train on the Bridge, a 1950s era SA Railways train repurposed as a luxury hotel.

The bridge over the Sabie River at Skukuza has been used in emergencies during floods, when the low-level bridges were damaged or too unsafe to cross.

‘We drew a lot from those early days,’ operations manager Gavin Ferreira told me. ‘We wanted to sleep on the bridge like they did, move onto land for a banquet, and sit and listen to stories round the fire.’

The train, permanently situated on the bridge, will have 24 ensuite carriage rooms, each sleeping two. A lounge carriage and a pool deck will also be stationed on the bridge, with the pool extended over the edge of the bridge above the Sabie River. On land, an additional seven rooms will accommodate 14 people, bringing the total for the hotel to 62. A pool, a restaurant and a reception area are situated on the banks of the river, where guests will dine and check in.

‘We’ve played with this old-world charm,’ says Gavin, ‘but in terms of train expectations, it’s something completely different for our guests.’

Kitted out with five-star amenities, the carriages are designed with windows on one side, giving privacy to guests and directing the view away from Skukuza rest camp. Each carriage room is fitted with a bathtub, shower, king-size bed, fridge and air conditioner, a far cry from the original transporter trains that parked on this bridge.

‘The game below the bridge is incredible, you can’t believe the things we’ve seen during the building process,’ Gavin told me. ‘The vantage point from the bridge is going to allow for a very unique game- viewing experience.’

The Shalati Train on the Bridge pays homage to a bygone era of glamorous train travel, while the Kruger Station is all about nostalgia. Just as generations past fondly recall their favourite camps and rituals, perhaps a whole generation of children will grow up fondly remembering licking an ice cream from the station, and watching 360-degree films in their pyjamas the evenings.

Kruger Shalati Train on the Bridge hotel opened its doors in mid-December.

From R8 950 pp sharing. Opening specials from R4 950 pp.

krugershalati.com

Did you know?

The Selati Line remained in use until the 1960s, with up to 250 trains a week rumbling through the Kruger Park. The last train rolled through in 1973.

James Stevenson-Hamilton was called Skukuza, which means ‘to sweep,’ a name given to him by Tsonga speaking people for his determination to sweep clean the park of poachers and other criminals in the area.

The Selati Line is sometimes referred to as the ‘man-a-mile-line’, so called because of the high mortality rate among its builders – some died of malaria and others became the victims of lions.

But Wait, there’s more…

2020 also saw the opening of Skukuza Safari Lodge, a 178-unit hotel in Skukuza. The three-star hotel fills a category between self-catering bungalows and high-end private lodges of Kruger. With a swimming pool, private gym and restaurant, Skukuza Safari Lodge will accomodate conferences guests and overnighters wanting a catered option.

From R2 730

for two sharing. Tel 013 329 000

skukuzalodge.com