The rangers protecting Kenya’s vast and pristine wild spaces have been badly affected by pandemic-related funding cuts, as filmmakers Robbie, Josh, Jasper and Ivo discovered while filming in the country. This prompted them to bring attention to the work – and challenges – of these rangers.

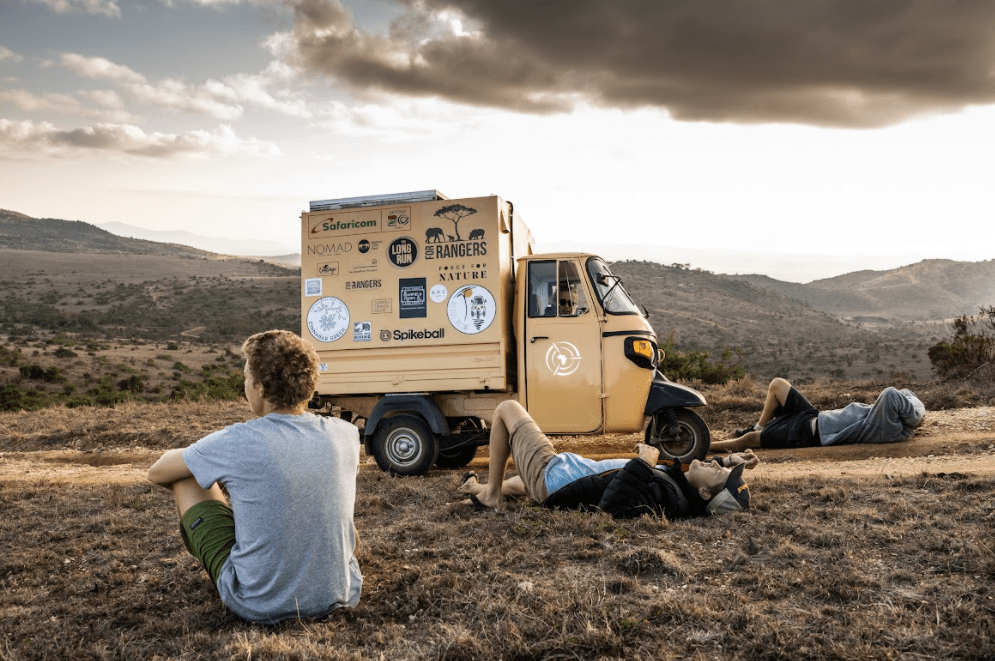

With film equipment being their only possessions, they rounded up a couple of tuk-tuks, and are taking them on an overland trip to Cape Town while are recording their trip as a way to focus awareness on these rangers. Josh gave us the rundown of what motivated the four to take this journey.

Written By Josh Porter

Having all lost our jobs and purpose in life thanks to Covid, it was time to re-evaluate. We were one year into the pandemic and the tactic of waiting till it blew over was not paying off. I was making YouTube videos in my dad’s shed, Jasper ditched his Canadian work visa, Ivo was tutoring neighbourhood kids and Robbie was doing some welding for his uncle. All in our twenties, all living with our parents. Something needed to change.

A phone call from Kenya in January 2020 set the ball rolling.

Jasper, Ivo and Robbie had decided to save money by living off the land and sea on a Kenyan island called Kiwyu, just south of the Somalian border.

Meanwhile, I was editing videos in a shed in the north of England that I’d taken during my time working in Indonesia and posting them on TikTok. I had made a video on black soldier fly maggots that was on four million views within a week of being posted and I had 100,000 followers. Then came the call from Kiwyu.

We quickly outlined a vague plan of joining forces, making videos and attempting to build something ourselves rather than waiting for the pandemic to end.

I flew out to Kenya and we made videos using our phones. Without international tourists, we had huge areas of wildlands to camp in and explore, editing together short stories of our travels.

Brands such as Mastercard began to sponsor videos and we were able to afford camera gear, microphones and drones.

We learned how to film, edit, record sound and tell stories through video.

Our films were centred on short camping stories trekking to waterfalls, fishing in rivers and driving through deserts. Almost all of these locations were under the stewardship of wildlife rangers and we would intently listen to their stories of wildlife rescues, drought and the pandemic.

We learned that the wild ecosystems we had been enjoying were under serious strain because of Covid. Loss of international tourism meant the loss of a huge source of revenue for conservation and communities. People who previously benefited from this revenue were forced to adapt, with some resorting to illegal logging, charcoaling and poaching. This presented a huge problem to wildlife rangers, most of whom work within the communities in which they grew up.

Covid and conservation

It’s not a case of wildlife rangers on one side and community on the other. Rangers are there to act as a link between people and wildlife, to ensure both are safe and able to flourish.

They would deliver workshops with farmers about how to better protect their herds from predators, would respond to calls about crop-raiding elephants to prevent violent clashes, and meet with elders to discuss the best path forward for both conservation and communities.

There have been many conservation victories in East Africa over the past 20 years. Elephant poaching, for example, has been almost completely halted. Rangers have been vital to this, maintaining the careful balance between people and nature. Many of the rangers we spoke to told us their workload had doubled and their wages had halved during the pandemic. This seemed desperately unfair and our adventure videos were suddenly far less important.

Our evening discussions around a campfire became centred on one topic: was there anything we could do? We may not have the skills or equipment to do this story justice but we decided to give it a crack.

We wanted to make a short documentary about the effect Covid was having on conservation and, with a bit of luck, get some attention and funding for the people who needed it. We set off into the Kenyan bush with a DJI Osmo pocket, a drone and a microphone.

After a few days of driving, we found ourselves in the Ndoto Mountains, land of the Samburu. They pride themselves on their ability to live in harmony with the environment. It is breathtaking.

The Milgis Lugger seasonal watercourse is almost a kilometre wide and plunges through a series of perfectly formed mountains. The land shifts from arid desert to lush jungle, to mountainous forest in a matter of 10km.

We met Moses, a senior ranger of the Milgis Trust who was born in the community he now serves. He spoke passionately about how he has watched his area suffer. Tourists had paid large sums to go on walking safaris through the Ndotos, with the money being distributed between community projects and wildlife protection, but the tourists were gone.

It is taboo in Samburu culture to cut down trees for charcoal but you could see the smoke rising from the sides of roads. Game animals that were previously plentiful and protected were now being caught in wire snares. Sandalwood trees that had been illegally logged elsewhere in Kenya had thrived under the protection of the Samburu. Since the pandemic, these trees were being felled.

Schools that the Milgis Trust had funded through international donors were now at risk of closure. Moses had high hopes for the prospects of children from the Ndotos, but now he feared they would be forced out of school and fall behind other children in Kenya, in a world that is modernising rapidly.

The Joint Operations Command Centre in Lewa invited us to come and gain a better understanding of the scale of the problem. It was harrowing. The year after the global lockdown in March 2020, rangers encountered twice as many incidents of illegal activity compared to the year before.

Each incident had a case report, containing pictures and descriptions of what happened. Images of children holding flashlights and knives, next to the bodies of 50 dik-diks were commonplace.

The severed head of an albino giraffe, photographed on the side of the road, was all that was recovered after poachers had butchered the body. A map of Kenya was littered with small coloured dots, each representing a different event that rangers had to deal with.

Most of the time the rangers are responding to calls from local people seeking assistance. Sometimes these reports place them in serious danger. In 2020 a community whose cattle had been stolen called the rangers for help. The rangers who arrived at the scene were fired upon by the cattle raiders.

One was killed and one was seriously injured. We later learned that a charity set up in Kenya had stepped in to help. “For Rangers” is a charity that operates throughout sub-Saharan Africa to support wildlife rangers. The documentary we were filming could indirectly lead to more funding for conservation… but now we began to think of ways that we could try to raise some money ourselves.

One fateful night

While talking about whether we could use TikTok to raise money, somebody’s brain lagged and they called it Tuk Tuk… and before you knew it, three hours of excited discussion had passed. We’d spend the last of our funds on two tuk-tuks and drive them from Kenya to Cape Town, filming inspiring stories of rangers and their communities while raising money for charity along the way.

Fast-forward to November 2020 and we were off, the two tuk-tuks full of camping gear and filming equipment. And we had a vague idea of where we’re going; you’ll have to follow us to find out.

View this post on Instagram

Follow Tuksouth on their journey on Instagram or visit their website here.

Pictures: Tuksouth

ALSO READ