Wild dog tracking is an adventure in itself but catching up to the predatory pack is the ultimate prize on this safari with a difference.

Words and photos Jocelin Kagan

It’s faint, one beep coming from that direction,’ said Catelin Markram of Wildlife ACT, pointing into the bush. We were tracking the Siyavikela pack of defiant African wild dogs that had broken out of Manyoni Private Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal. The telemetry aerial was our only contact with the three pups and six adults now joyously exploring the new terrain where we were tracking them on Thanda, a neighbouring wildlife reserve.

I asked how they escaped. ‘Pushed under the fence,’ Cate said. The dogs are wily and smart. As with all predators, if the opportunity to wriggle

under a fence presents itself, they’ll take it. Although electrified barriers have proven successful in keeping wild dogs within protected areas, in this case the fence was compromised. With rescued pangolins recently introduced onto the reserve, the bottom line had been disconnected making it easier for the dogs (as well as hyenas, leopards and lions) to find a wiggle point. It’s a difficult task managing the fence: keep the predators at bay but risk pangolins getting stuck by their scales, or switch it off and go in search of escapees? The ultimate choice meant we were urgently trying to locate the pack and entice it to return home.

Five of the six adults were collared. One collar had had its aerial chewed off, no doubt in a game of romp, and our most reliable contact was one strong signal beeping on Cate’s hand-held telemetry receiver/radio. The collar was also being picked up via satellite, ‘signing in’ twice a day to give its location. But it’s not an exact science; if the cloud cover is too thick, or the dog is in dense bush or at the bottom of a deep ravine, chances are a signal won’t be received.

Wild dogs have a hunting success rate much higher than many other predators, in part because of anatomical adaptations in their limbs for stealth and endurance while running to exhaust prey.

Around another turn and there we spotted them: two adult females, four males and three of the cutest pups. I leapt for my camera and started shooting. The dogs were twitchy. They stopped and stared at us but were not interested in exploring where the smell of bait, an impala carcass at the back of our truck, came from. No doubt our human presence deterred them. We, on the other hand, were counting tails and breathing a collective sigh of relief. All were present and in good condition; the pups looked magnificent, all shiny coats and bright eyes. Then the family

suddenly moved off. Being slim-bodied, they eased into the thick bush, not the preferred territory of lions or hyenas, the dog’s natural enemies. The pack vanished in a blink.

Wild dog tracking requires patience, experience and care. The tracking team manages wildlife in tough environments and situations where their best efforts are often thwarted. Right then Cate of Wildlife ACT, Dane Antrobus, the resident ecologist, Karen Odendaal, managing director of Manyoni Private Game Reserve, my guide ‘FP’ of Zululand Explorers, and Kent Lovelock from the Thanda Wildlife team were in radio and cellphone contact. The airwaves were alive with questions and directions but it was after 9am, the dogs had found shade in thick bush and gone flat. We had an idea where they were but without road access we couldn’t get close, and walking in this area was out of the question… who knew what might be lurking?

That afternoon we returned to the spot where the signal was strongest and were delighted when it started to move. Up the steepest, rockiest of roads we traced the signal which grew stronger and stronger. Then as we jolted to a stop, there they were near the fence line, having a glorious time cavorting in the bushes, chittering and squealing with delight. We basked in their exuberance, and before long they were off again, disappearing back into thick bush. We couldn’t follow and returned to the comfort of Leopard Mountain Lodge, satisfied that their numbers were intact, there was no evidence of snaring, no skin was broken and no dog displayed injury.

Hyenas and wild dogs often clash after a kill, resulting in fierce interactions as the brazen scavengers are chased off by the pack trying to protect their food

Back out at 5am the following morning, our assumption was that the dogs would have made a kill in the area where they left us. But no. We drove and drove until Cate eventually picked up a faint signal. ‘That way,’ and we were off down the track only to be confronted by a gate and fence line along the edge of a steep and rocky hill.

Tension mounted. Communications between Cate and home base were filled with concern. The other side of the fence was community land which did not bode well for the dogs. Then the beep grew louder and other signals could also be heard meaning they were coming closer. I grabbed my camera and we scrambled up the steep rocky incline. Our stamina and fitness tested, we moved at speed, breath coming fast and our chests heaving.

Suddenly, an anti-poaching team materialised from the bush. ‘Yes, the dogs are through a hole in the fence. They are on the other side,’ the leader said. Our worst fears were confirmed.

We finally crested what seemed like a mountain and to our relief, Cate spotted the pups inside the fence line. FP raced over the crest to examine the scene and returned with the details. The dogs had chased a nyala right through the fence and feasted on the other side. FP crawled through and threw the remains of the carcass inside the reserve, a morsel to keep the pups there and hopefully induce the adults to return.

after about nine months pups begin learning to hunt by observing and following adults, thereby developing the skills and techniques required for co-operative hunting.

Reports were sent to home base. The Wildlife ACT team weighed up the options: do they play the ‘Whoo Call’ – a recorded distress signal which usually attracts the dogs to investigate? Do they drop a carcass and broadcast the excited sounds of wild dogs eating to entice the adults back inside the fence? (The risk being they think it’s another pack, become spooked and go deeper into danger). The sun was high, the beep constant, not moving. The pups had settled in shade to wait – the adults were obviously sleeping – and we returned to Manyoni.

Back out that evening, after we scrambled up the hill again, the signals remained strong but immobile. Eventually the shadows grew long and with it the chance of encountering other predators at night. We had no choice but to leave the dogs in the gloaming and hope they would reunite with their pups on the Thanda side of the fence. They did that night, and the pack settled down to a comfortable almost predator-free existence in Thanda.

Seven months later…

The Alpha female produced a litter of eight pups at the end of November, her second in a year which is unusual as wild dogs generally only den once a year. When the pups are old enough, Manyoni plans to bring the pack back into its reserve. In the meantime, the Wildlife ACT team is monitoring the pack to ensure they are doing well and are safe.

Challenges versus rewards

Making the effort worth it

As you can see by this article, keeping wild dogs (as well as larger predators and other endangered animals) is high maintenance, one of the reasons many reserve managers decline to host the species.

But let’s consider the payback in terms of tourism: African wild dogs are unique to the continent. Sightings are either by chance or design – they are thrilling and dynamic to observe. Wild dogs top the list of animals people want to see when returning to the bush. Photographers want to catch pups looking cute, families at play, and dogs on the hunt. Tourists want the excitement of the chase, the thrill of spotting a hyena having its bottom nipped by the dogs as they protect their kill. Tracking wild dogs – one of the most successful predators in Africa – offers an unequalled experience, a reward that potentially outweighs the effort.

There are dedicated organisations in place ready to assist when necessary.

• Wildlife ACT has a wealth of knowledge, its network is international and they will readily share expertise with those willing to ask. wildlifeact.com

• WAG, Wild Dog Advisory Group headed by Dr Harriet Davies-Mostert has volunteers from across the board. Over 40 conservationists and the full spectrum of academics are ready to help. Want toknow how to build a wild dog boma? Ask WAG, they will discuss an optimum design for your situation. Want to bond two breakaway dog clusters into a pack?

Ask WAG. wagsa.org.za

• The Bateleurs assist with wild dog translocation, flying the dogs to new homes. bataleurs.co.za

• Private helicopter owners often assist with their machines and pilots by arrangement if they are needed to track or capture the dogs in hostile territory. For the species to survive into the long-term, new sustainable reserves need to be found. Co-operation between reserves is critical to all wildlife survival and especially for wild dogs. So why go to all this trouble? The African wild dog is a unique species which has been adapting since it broke from its grey wolf ancestor 1.7million years ago. It’s made it this far and it deserves to carry on.

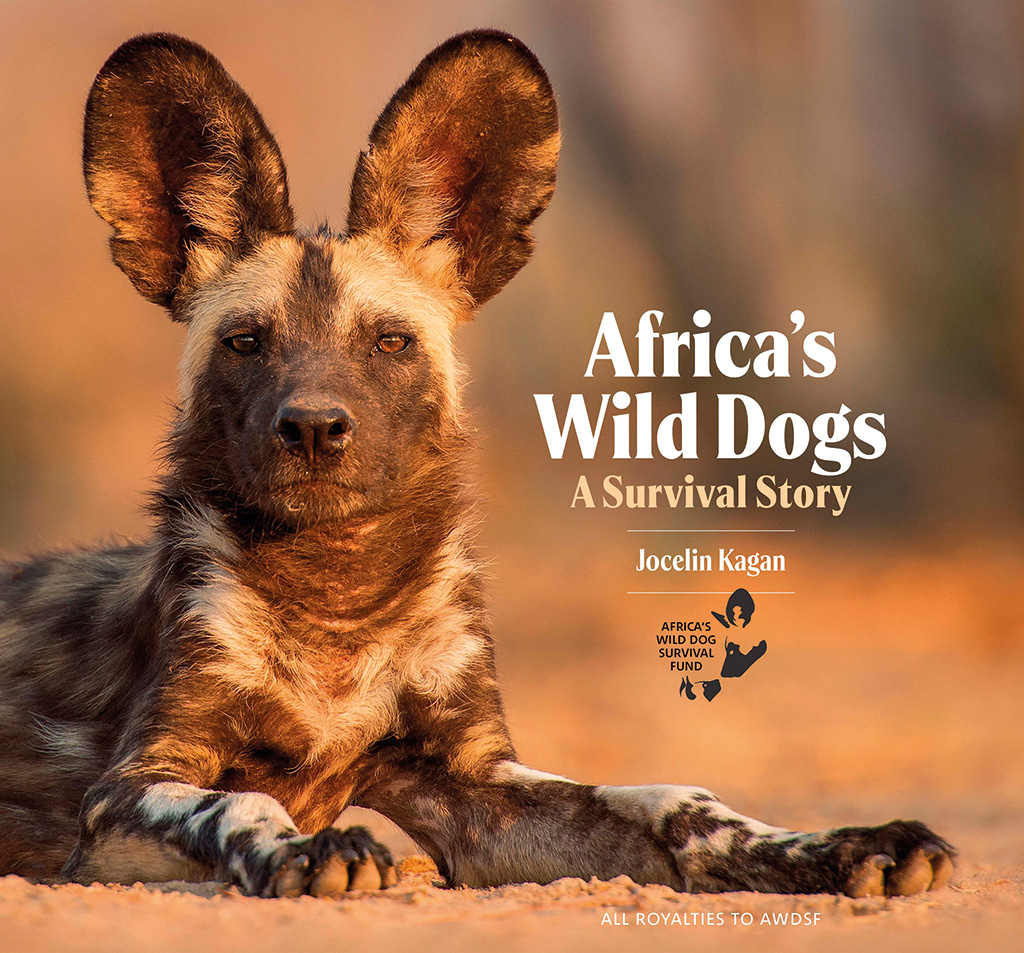

Jocelin Kagan is the author of Africa’s Wild Dogs – A Survival Story, and is the founder of Africa’s Wild Dog Survival Fund. Donate at kagan.co.za

Do This

Wild Dog Tracking is an adventure with a difference. It’s purposeful and engaging. More so, I gained a deep appreciation for those working on the ground – the dedicated men and women who keep the dogs as safe as possible. And doing this, then returning to a hot shower, and a mouth-

watering menu at a top class safari lodge – who could ask for more?

There are opportunities to track wild dogs as a volunteer, student or on a Conservation Safari with Wildlife ACT who are priority species monitors at Mkuze Game Reserve, Hluhluwe iMfolozi Park, Tembe Elephant Park and Manyoni Private Game Reserves.

087 802 1231

wildlifeact.com