‘I saw the ground rolling towards us like waves. Later, we heard that it lasted for 30 seconds, but to us it felt like an eternity, that what was happening would never stop.’

Anneline Fredericks was just 18 when the Tulbagh earthquake struck in 1969, still the worst earthquake to hit South Africa.

It was a cool spring night, sleepy Boland towns peaceful in the quiet. But this was the calm before the storm. For beneath the fertile soil, unbeknownst to farmers and villagers alike, the restless Earth was moving.

At 10:04pm, the ground started to shake violently, terrifying residents. Many thought that the last judgement had arrived and the world was ending.

Nearly 53 years ago, on 29 September 1969, an earthquake struck the Boland farming towns of Tulbagh, Wolseley and Ceres, leaving a trail of devastation in its wake.

The clock of the local church stopped at 10:04pm, the exact time the earthquake hit

Why earthquakes occur

Most naturally occurring earthquakes are caused by the movement of tectonic plates, which are massive slabs of solid rock that form part of the Earth’s crust and uppermost mantle. They are always moving.

Earthquakes mostly occur on plate boundaries where the most movement is. They can also occur far away from these boundaries, at faults, which can be natural or man-made, for example by deep mining or filling dams. This is called induced seismicity.

The Witwatersrand is known to have tremors caused by the extensive mining on the reef.

South Africa is far from tectonic boundaries, which means damaging natural earthquakes are rare.

The night of the quake

Many were shocked to hear the news of the devastating earthquake that swept through Tulbagh that night. The tremor tore through neighbouring towns Wolseley, Ceres and Prince Alfred Hamlet.

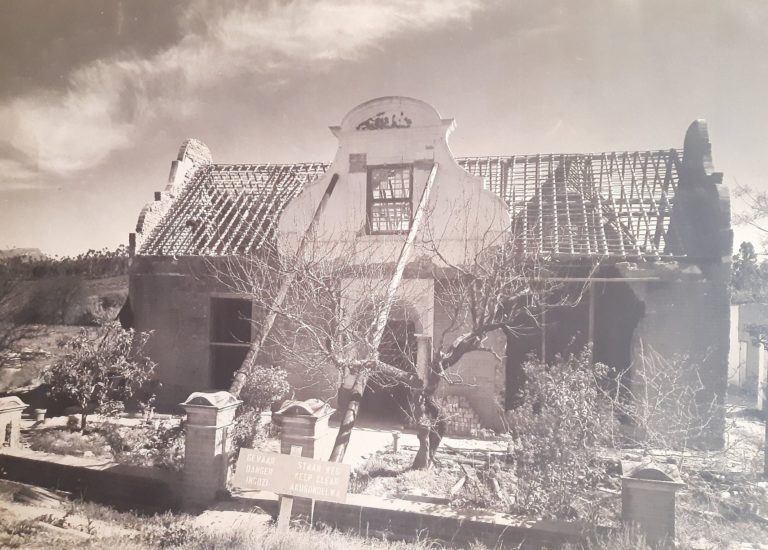

Tulbagh, hit the hardest, suffered severe structural damage to valued historical buildings, among other things.

The Drostdy at Tulbagh

The quake registered a magnitude of 6.3 on the Richter scale as well as an intensity of VII on the Mercalli scale. These readings were done using previous models of both the Richter and Mercalli scales.

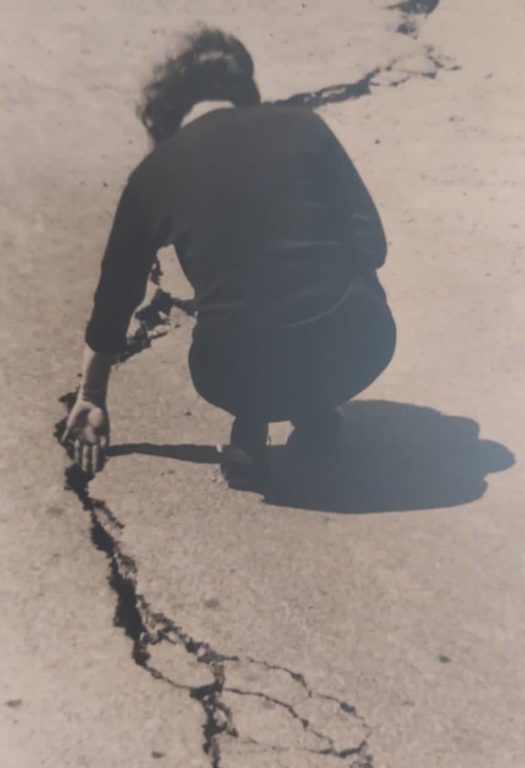

Sand boils only appear when a strength of IX is measured on the earlier model of the Mercalli scale

When the earthquake was measured at South Africa’s geomagnetic research facility in Hermanus, the seismograph’s needle went haywire.

The tremor was powerful enough to scare people in Cape Town and was felt as far as Durban, about 1 175km away.

It was caused by a strike-slip fault, which happens when two plates move horizontally past each other. The initial shock is said to have lasted between 30 and 90 seconds. Rockslides in the surrounding mountains ignited rapid and extensive mountain fires in a matter of seconds.

Witzenberg

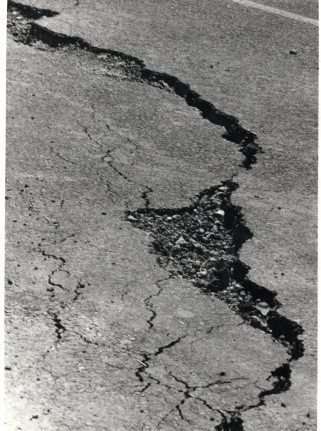

Telephone connection, electricity and water supply were cut off. Many access roads and passes, such as Bainskloof, Michell’s, Nieuwekloof and Du Toit’s Kloof, were blocked by rock falls from the sloping mountains, or closed off because of cracks.

The aftermath

A radio call from Tulbagh via Wellington was sent after 11pm, asking for all possible help and reinforcements. The call was answered by Paarl police, who responded immediately.

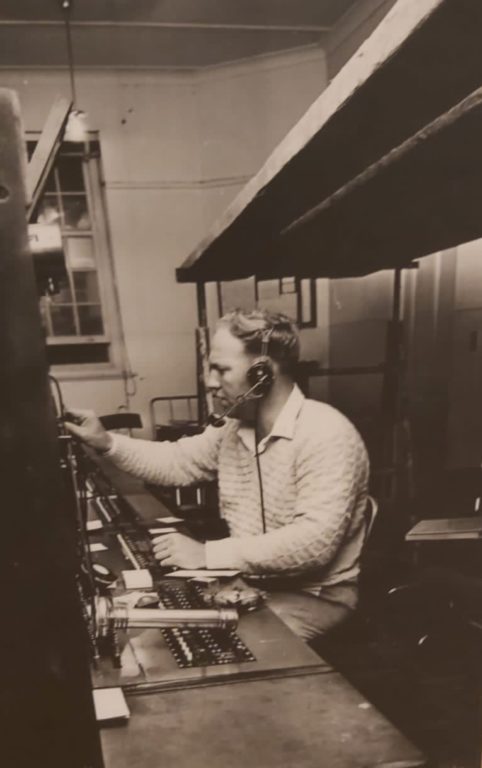

Mr D Hougaard manning the Tulbagh exchange during the quake

The quake claimed 11 lives – one adult and the rest children under the age of eight. Tulbagh was declared a disaster area.

Army units arriving in Tulbagh the morning after the earthquake

Soldiers stationed outside the Tulbagh library

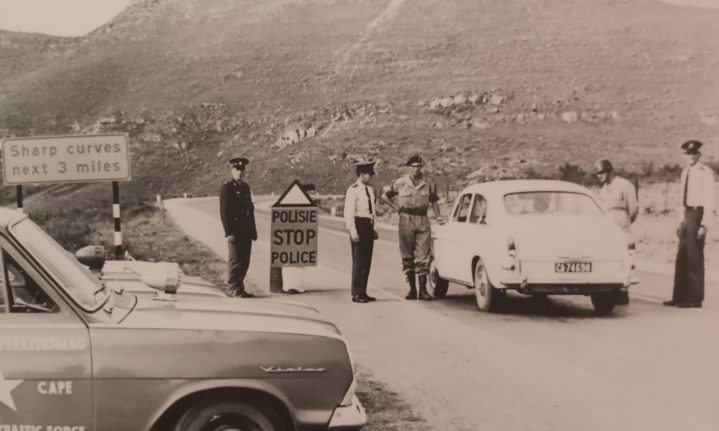

The South African Police and the Defence Force quickly responded. The police and units from the army arrived within 24 hours and provided emergency services and field kitchens.

About 3 000 tents were erected on showgrounds and school fields for temporary accommodation, though residents lived in these tents for over a year, often through harsh weather.

The Defence Force sent 230 men in seven helicopters and 20 heavy-duty trucks to transport heavy pipes into the mountains to restore the water supply.

The government quickly set up a disaster fund, which went towards building new housing for town residents.

Aftershocks persisted for a year following the initial quake, while the Tulbagh community slowly recovered.

Remembering the Tulbagh earthquake

Anneline Fredericks recalled a light tremor that occurred nearly 12 hours before the quake struck.

‘Around 12 o’clock there was a tremor and we wondered what that was. But they were busy blasting dynamite for the Nieuwekloof Pass and Voëlvlei Dam. So we chalked it up to dynamite blasts because it was really loud, unaware of what was in store for us in the evening.’

Anneline, her sister and her sister’s boyfriend were walking home when the earthquake struck.

‘That time it was still gravel road … there weren’t streetlights. There were poles with electric cables, but no light.

‘At once there was this rumbling and grumbling, almost like those loud thunderstrokes when they clash against each other. We stopped in our tracks, thinking what is going on? This is different from normal thunder,

Anneline (far left) and her family the day after the earthquake

‘We stood there holding each other tightly as we listened to the rumbling and grumbling. The trees shook from the ground, tipped out with roots and all. The electrical cables tightened, snapped and fell down.

‘There were sparks everywhere and we had to jump out of the way.

‘As we stood there, we thought judgement day had arrived – you know how people say that the world will end in fire and brimstone. We began to pray. As we stood there, we heard the screams and cries from all those people who wanted to storm out of their homes. Sometimes it feels like I can still hear it because they were such anguished screams.’

Anneline had her church confirmation in her tent

Anneline remembers the immediate aftermath, too.

‘If you had a car back then, then you were very classy. Our postman had a car and he lived next to us. They were out the house, and his wife was yelling at him “Pieter, Pieter! Kom ons moet ry, ons moet ry!” (Pieter, Pieter! We need to drive, we need to drive!)

‘Many people climbed into their cars but they were stopped at the hill by the army, because roads in and out were closed.

‘I told my brother and sister “Ek sê vir julle, wag julle net tot Oom Pieter uit daai garage uit trek, dan is ons almal in daai kar.” (Just wait until Uncle Pieter pulls that car out of that garage, then we are all in that car.)

‘When they opened in front, we opened the back. We only made it to the hill then we had to turn around.’

Lena Manas lived behind Saronskop, in the epicentre.

‘There weren’t people who lived near us. But this evening we sat down to do family worship. The dogs suddenly started howling and barking. And there came this rumbling, the house shook, things fell and we opened the curtains to look out the window. There in the mountains the lights kept going on and off. We heard how the rocks rolled.’

But it was not the earthquake itself that upset her.

‘My sister was pregnant and they lived at Tulbagh Station. We went to her tent. That evening it was raining terribly. We realised she was in labour but she was struggling. Then we realised the baby was in breech position. She suffered for a long time.

‘When her son was born, the baby didn’t cry. I splashed him in the face with water while my sister was just frantically tapping him until he finally cried.

‘What was so painful for me, was that during the earthquake and the storms, that she had to have a breech baby as well.’

Heleen Fortuin recalls how tumultuous the evening was.

‘The entire world is full of dust and I don’t know where to go. I grabbed my baby, she was three months old, and just after I grabbed her, a big chunk of brick fell right on the place where she was laying. If I hadn’t grabbed her in time, then she would’ve been underneath the ground today, too.’

Aerial view of tents

‘Everyone was on the rugby field. That night the elderly prayed prayers that I had never prayed. When I heard them, all I could do was sit still with my heart aching. The way they were begging God for mercy. It was a terrible night.’

Today

Positives did come out of the disaster. All of the buildings on Church Street were rebuilt. The museum and the street became major tourist attractions that stimulated the town’s economy.

Dr Ray Durrheim, a seismology professor who felt the quake in Cape Town when he was a teenager, said the quake ‘jolted South Africa out of complacency regarding the risks posed by earthquakes, and the National Seismograph Network was established shortly thereafter’.

A special thanks to:

Anneline Fredericks, Lena Manas and Heleen Fortuin for telling their stories.

Dr Ray Durrheim from the University of the Witwatersrand and Dr Alastair Sloan from the University of Cape Town for assisting with the geological information.

Shurine van Niekerk from the Tulbagh Earthquake Museum for her help and insight.

Pictures: All pictures are property of the Tulbagh Earthquake Museum

ALSO READ