St Helena is one of the earth’s most isolated inhabited islands, boasting jaw-dropping landscapes, fascinating natural history, and contemporary politics.

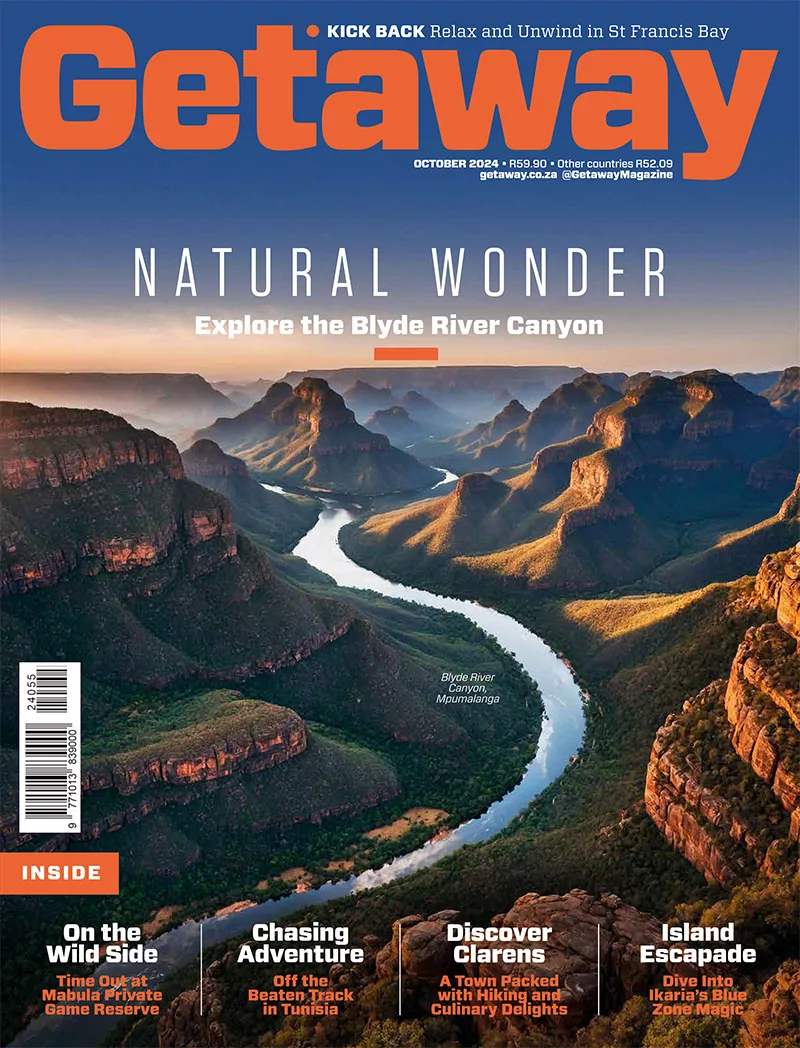

Why visit?

- St Helena is a naturalist’s nirvana.

- It’s a great hiking destination with 21 demarcated walks.

- It has a rich and exciting history. It was discovered by chance in 1502 and kept secret for over 80 years. The island has flown the Union Jack since 1659, apart from a brief Dutch invasion.

- Before the first commercial test flight (operated by Comair) landed on St Helena in mid-April 2016, visitors took a five-day voyage on the RMS St Helena.

The end of an era

‘This next song goes out to Ashley, who passed his driver’s licence today. It’s an old favourite here on Saint FM: Shania Twain’s Don’t Be Stupid. Dedicated by your mom.’

The DJ’s words plop out from the speakers of my rental car and then float, buoyed by an arcane British register that sounds like a Kiwi attempting a Jamaican accent. I’ve little time to consider the parochial. There’s a single-lane road ahead of me snaking its way up the side of a stark ridge like a string of charred spaghetti tossed against a loaf of rye, and there’s a neon-blue Subaru with a dropped suspension bearing down on me. Below, the corrugated Georgian roofs of Jamestown, a streak of civilisation wedged in an otherwise barren valley, offer little comfort. We both stop. I shift the stick into reverse and back down to a place where the road is wide enough for two cars abreast, en passant. The driver waves and smiles as he accelerates by inches from my fender. Cripes. Perhaps passing your driver’s here is actually a big deal.

It’s my third day on St Helena, considered one of the remotest inhabited islands on Earth. I arrived on the RMS St Helena, a five-day voyage from Cape Town that was one of the two last ships still carrying the venerated British title of a working Royal Mail Ship. It used to be the only thing that connected its 4000-odd inhabitants, known as Saints, to the outside world. Here, on this 122-square-kilometre patch of volcanic rock, it’s a digital detoxer’s bliss. But it’s not a quintessential island paradise. Bleached beaches and neon cocktails? Forget it. Glitzy hotels with sparkly pools? No sir. This is a rock. But my, oh my, what a rock it is. History, politics, and raw, unbridled beauty are all here on this volcanic wonderwork – a microcosm of the planet on the cusp of change.

The varied landscapes of St Helena contrast beautifully with the seemingly infinite ocean beyond.

But first, let’s go back a few million years. How did life come to exist here on this geological neophyte that missed the supercontinent Pangaea’s divorce party by almost two hundred million years?

Consider this: 14 million years ago, as Africa’s Great Rift pushed, crushed, and rose up against the Arabian plate, somewhere in the South Atlantic, the liquid fire mantle beneath the earth’s surface burst through a widening crust on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, spouting from the ocean floor, solidifying, growing and heaving until it gurgled and spat its way to the surface. Magma exploded high into a blackened sky and then plunged back towards Triton in a demonic meeting that boiled, bellowed, and steamed like a wet beast branded with a hot iron. And there it was: St Helena – a bedlam of ash and lava. But not for long. Colonisation, at its most primordial, happened.

Cyanoplankton was one of the first to arrive. Carried on the feet of seabirds, they began feasting on volcanic deposits and lava flows, sometimes growing into thick gelatinous nutrient banks on the sterile rock. Lichen and mosses arrived similarly. Soon, other hitchhikers began to make withdrawals. Seeds hid in the digestive system of seabirds, surviving the flight from Africa without being pooped out in the mid-Atlantic. Ultra-light fern spores hopped on long-distance air currents, headed for a new life. Heavier wayfarers: unopened seed capsules of ebony, redwood, and dwarf trees rode the oceanic drift and washed up on the island’s shores, drying and opening so that their inhabitants could alight and begin their immigrant life. Many of these journeys ended in vain. Drownings, navigational tragedies, and premature evacuations were more common than not. But in the game of evolutionary chance, time is an ace up the sleeve. Given enough of it, life will find a way. And that, like the Galapagos, Vanuatu, and nearby Ascension, is what makes St Helena an explorer naturalist’s nirvana.

Fairy terns are the only seabirds to nest inland on St Helena.

So I join Laurent Bate Roullin, a researcher with the St Helena National Trust, on a hike of exploration. We slip down a narrow cobbled alleyway in Jamestown and onto an old gravel donkey track that curves around the town’s eastern ridge. Ghost-white fairy terns bicker over grass and twigs in the afternoon light, arriving from sea scavengers with chuffed, swollen black melanite eyes. Ahead, Laurent’s boots crunch the loose gravel as we pass a string of beaten-down fortifications cleft into the indomitable coastline. This hostile terrain made St Helena a prized possession for the colonising British, who sent their enemies to perish here. Not least of all was Napoleon, who was left to pace, plot, and brood in his incarceration at Longwood House after being captured at the Battle of Waterloo. Exiled here, too, were 6000 South Africans imprisoned in Boer War camps and, later, the Zulu King Dinuzulu.

We turn inland, cut through a valley, and onto the island’s windward plains. To the west, a shamrock-green ridge ascends to Diana’s Peak, the highest point. Ahead of us, the island’s last surviving endemic land bird, the wirebird plover, incubates its eggs in the short grass. It darts wildly away from its nest when approached, feigning distress to distract predators. It’s a hazardous survival mechanism, and of the other eight avian species that became extinct, I wonder how this genus survived. As we continue, the scenery changes with unrivalled immediacy. Grass turns to semi-arid desert, streaked with colour, like a sandy palette primed by an artist’s brush.

The windward side of St Helena looms on the horizon, a rocky salvation for sailors of days past.

And I remember, again, how I got here. Sadly, the voyage of nostalgia from Cape Town is one you’ll never make. Its decommission date was tied to the airport’s completion, first projected as far back as 2012. Many locals joke that St Helena is a place that’s perpetually building an airport. In May 2016, it will finally be completed. In place of the five-day oceanic reverie that slows you to the pace of island life, it’s a five-hour dash from Johannesburg. And, of course, things will change. They have to. Tasked with tug boating this rock into 21st-century commercial viability – over the years, it has failed to make itself economically sustainable in various industries such as quinine, flax, lace, fish canning, and even stamps – its controlling authorities are fluffing the pillows and shining the silverware, incentivising locals to join a tourism revolution. But it’s not easy.

LEFT: With a population of 850, Jamestown is wedged in James Valley with no room to grow. RIGHT: The Papanui (wrecked after it caught fire in 1911) is an easy snorkel from the shore in James Bay.

Unlike the peculiar passion for fast cars on an island with emaciated corkscrew roads that rarely let you get above 30km/h, the friendly Saints approach business and employment with somewhat less gusto. Historical failure in trade and an imported aid budget seems to have cultivated a hereditary idleness. There is not much work, stores are often closed, and taxis are nowhere to be found. At the White Horse, a dimly lit pub in Jamestown with two one-arm bandits and one two-armed barman, one of the locals grumbles about change and how the airport, too, will fail. It facilitates a conversation that I find about as riveting as bread. Change here is vital for survival. The colonial time capsule will crack, and nostalgic travellers will cry. But there’s one thing that won’t change; for me, it’s the reason to visit. The real allure of St Helena is its natural beauty. With careful planning by its tourism and conservation departments, it will hopefully remain as such.

LEFT: The hike to Bank’s Battery is peppered with abandoned fortifications to explore. RIGHT: Curious sheep greet visitors staying at Farm Lodge.

I’m on the same road back into town a few days later. A DJ’s voice comes on, ‘The World [a cruise liner] is anchored off the harbour. Passengers are coming ashore. Anyone with a car, come down and pick ‘em up to make a little money.’ The announcement sparks about as much interest as a Golden Girls marathon. It’s Easter Saturday. Everything is closed. Bemused passengers wander the abandoned streets and then shuffle to the dock to be whisked back to their vessel. The Saints are nowhere to be found. They’ve gone camping in a nearby valley. The world had come to visit, and nobody was home. I’m reminded of Niall’s comment that this attitude needs to change if St Helena is to be successful. But right then, I think, if I lived on an island this beautiful and it was Easter weekend, camping in the valley with the Saints is exactly where I’d be.

Getting there

Direct access to St Helena was only possible via the RMS St Helena (a stop-over on various cruise-liner itineraries). The first commercial flights were scheduled for May 2016 and signaled the end of the Cape Town to St Helena voyage. Comair commenced a weekly flight service every Saturday from Johannesburg on a 138-seat Boeing 737.

Yachts, anchored off James Bay, are often chartered by retired sailing couples on round-the-world adventures.

Need to know

All visitors to St Helena must provide proof of medical insurance for the duration of their stay. This is presented to the Immigrations Officer upon arrival. The currency is the St Helena pound and pound sterling (equivalent value). There are currently no ATMs. There is a bank that will cash travellers cheques and exchange rands for St Helena pounds. However, I’d advise changing money into pound sterling before you travel, as long queues often exist. Car rental, taxis, and various tours can be booked at St Helena Tourism, at the top of Main Street in Jamestown. It is also where you’ll learn everything you need to know about your stay. The staff are friendly and helpful. Make this your first stop upon arrival.

LEFT: A short hike to the top of Diana’s Peak on a clear day is the best way to take in the diverse landscape. RIGHT: In Jamestown, shopfronts are a throwback to the 1950s.

Things to do on St Helena

- Hike the island until you can’t anymore. There is no better way to explore St Helena than on foot. There are 21 demarcated walks on the island. They’re known as post-box walks because each summit has a post box containing a stamp and a visitor’s log. A booklet detailing the walks is available at the tourism office in Jamestown.

- Go on a 4×4 ride with Aaron’s Adventure Tour. It’s a superb way to see the lesser-visited areas of the island and get a local point of view.

- Contact: +29023987.

- Visit the Millennium Forest, where more than 10 000 gumwood trees were planted at the turn of the century as a St Helena National Trust conservation initiative. Visitors can contribute by planting a tree, too.

- Contact: +29022190

- Go scuba diving or fishing with Into the Blue. There is abundant marine life, and hawksbill turtles, whale sharks, and humpback whales are common sights. Sport fishing is also exceptional.

- Contact: +290 23459

- Snorkel to the Papanui, a steam passenger ship that caught fire and sunk in James Bay in 1911. Visitors can head out independently or contact Anthony Thomas for a guided swim.

- Contact: [email protected]

Where to stay in St Helena

You must book your accommodation well in advance. There are a limited number of places to stay, and central locations get booked quickly.

- Fowler’s Town House is a self-catering house in Jamestown with a double and single room, sleeping three. There is a courtyard with views over the town and James Bay, and it’s a short walk to the town centre.

fowlerssthelena.com - Coles Courtyard Hostel (also known as Coles Bunker) is a rustic hostel in Jamestown situated around a cobbled courtyard. There are individual rooms, but the St Helena National Trust owns it, and you’ll likely be sharing facilities with volunteers. It’s a great place to learn more about the biodiversity and natural history of the island. When I stayed there, one of the researchers was rearing an abandoned fairy tern chick, and fish guts were a regular find in the fridge.

Contact: +29022190 - Sleepy Hollow is a well-run, modern B&B situated above Jamestown in Half Tree Hollow. It has beautiful views, impeccable service, delicious breakfast, and Wi-Fi on request.

Contact: +1202 022 218 - Farm Lodge is a beautiful country house about 20 minutes from Jamestown. You don’t get better for countryside peace on an old working farm.

Contact: +29024040

Where to eat in St Helena

- Sunflower Café makes delicious local fare such as tuna bake and pilau. The menu is by request, and booking is essential and must be made at least one day in advance.

Contact: +29024145. - Anne’s Place is a great hangout in Castle Gardens in Jamestown. It has a tropical-diner feel; if you’re looking for company, this is where you’ll find it. Try the tuna steak or fishcakes.

Contact: +29022797.

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: A train through Africa part II: things go further awry