This is tiger season and you’re walking into tiger country now,’ came the words from a very concerned-looking shepherd living on the edge of the Namib Desert.

In these parts, everything is called by a different name: leopards are called tigers hyenas are called wolves, and hikers are called crazy. But I’m not some hardcore explorer and neither is Lauren, my wife. We’re just two normal people who set out to walk along the coast from the southernmost tip of Africa to the northernmost point of Namibia.

Erlo and Lauren Brown traverse a beach at Cape Point. Erlo used a tripod and remote trigger to capture photos of themselves in vast landscapes, where no one else was around to push the button.

I had a dream one night: I was on a beach with the cold Atlantic Ocean to my left and a white sandy desert to my right. I immediately realised that I was walking on the coastline of Namibia. The dream had such an impact on me that I got up at 3am to start figuring out how to do it. (In order to fund our walk, we taught English in South Korea for two years.)

A celebration, using poet Ian McCallum’s words, in their roadside camp, on the night before they reached the end of the walk at Epupa Falls.

Fast-forward to Day 1 of the walk: as I perched my camera on a small tripod in the parking lot of the Agulhas lighthouse, it suddenly dawned on me that we were about to do something outrageous. I was standing at the foot of Africa feeling immensely small and insignificant. We were literally walking into the unknown with nothing but our backpacks – no sponsors, no backup teams.

The plan was to follow the coast, literally walking and sleeping on the beach or as close to the sea as we could, and carrying all our food and water. During our trek, we’d take stock of the plastic pollution along the shoreline and count African black oystercatchers. This data was to be used by the Animal Demography Unit at UCT.

Wild camping for much of the journey, the couple swam in the ocean to keep clean – also, they discovered, cold water is good for tired muscles.

Making our way up the Cape West Coast, the tough conditions were made easier by the warm-hearted people we met. I remember one particularly hot and difficult day between Elands Bay and Lambert’s Bay. We were sitting on the beach, trying to catch our breath, when a guy came walking out of the sea with a spear gun in one hand and a fish in the other. He took one look at us and went to fetch ice-cold Klippies and Coke – pure Weskus hospitality.

It was not my first time walking in this region. In fact, I walked the entire South African coastline in 2010 with my border collie, Zeta. So this part of our trek was relatively straightforward, since we knew what to expect. We managed to walk on the beach all the way to Port Nolloth, where we traded in our backpacks for a homemade cart and hit the tar, skirting around the diamond mines to Alexander Bay. Then we headed inland along the Orange River, to cross the border into Namibia on the pontoon at Sendelingsdrif.

They tried to keep things simple, even walking barefoot when possible – here on Milnerton Beach.

Crossing into another country put this whole walk into perspective. It was the first time either of us had set foot on Namibian soil and, as we looked at the rocky, barren landscape in front of us, we sensed that we might have bitten off more than we could chew. We had already walked 1,373 kilometres, but another 2,200 kilometres lay ahead…

Skirting around the Sperrgebiet, Namibia’s restricted diamond area, we eventually made it to Lüderitz, looking forward to walking beside the sea again. However, after communicating with the authorities for the past seven months, we were still unsure whether we’d get permits to walk the concession coastline to Walvis Bay.

Resting under a giant quiver tree before pitching the tent for the night, on the road between Rosh Pinah and Aus.

We ended up spending three weeks in Lüderitz. After days of being sent from one person to the next, it became apparent that the only stretch of Namibia’s coastline we could gain access to would be the 250 kilometres of public access between Walvis Bay and the Ugab River mouth.

Giving up my dream of walking the Namibian coastline took a long time to accept, but in hindsight it worked out for the best. We saw much more of the country and were able to meet some very interesting people along the way. Our new route meant that we had to follow the gravel roads through the Namib Desert, trying to stay as close to the sea as possible. In reality, though, we were almost constantly more than 150 kilometres away from the ocean. We traded the coast, with its temperate climate, often cooled by mist and cold wind, for the desert and the wilderness of northern Namibia, which brought sun, heat and wild animals.

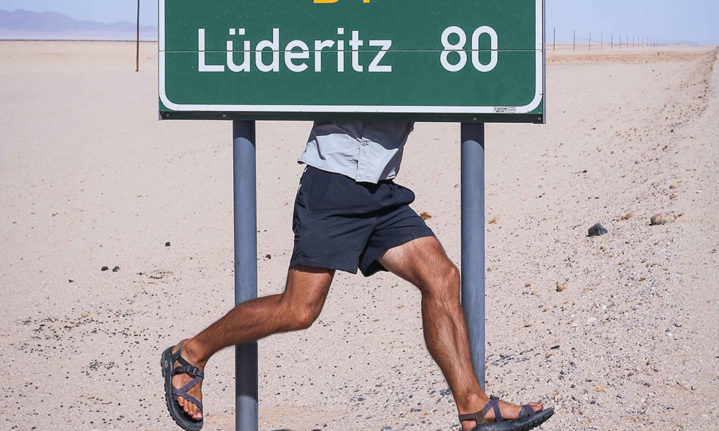

Road signs were often the most interesting feature in a barren landscape.

The landscape transformed from rocky and mountainous in the south to flat grassland plains and the sandy, rock-strewn hills of middle Namibia. Landscapes in this vast country change about every 20 kilometres, and when travelling by car, you might miss some of the nuances. But on foot, when you’ve been watching a tree come closer for the last 15 kilometres, every little change is a feast for the eyes – not to mention a gift of shade.

The Great East Wind, which blows in from the Kalahari and over the Namib Desert, made the going difficult at times.

We managed to make it through what we called ‘the valley of a thousand hills’, ending up in the Gaub Canyon, where we were caught in one of the worst thunderstorms we’ve ever experienced. It rained so much that the Gaub River flowed for the first time in many years.

This was a big landmark, and gave Erlo and Lauren an excuse to have a little fun while resting. The sign is north of Solitaire on the C14.

After making it to Walvis Bay, we headed along the beach again to Swakopmund and beyond, with lots of jackals keeping us company. One night, while camping about 50 kilometres inland from the Skeleton Coast, there was a sound so loud and eerie that I woke up sitting in a crouching position. Lauren tried to convince me that it was just a harmless jackal, but she knew as well as I did that we were dealing with a much larger animal. Sleeping in a tiny two- person tent didn’t seem like such a great idea any more. I grabbed my camera and torch while Lauren got out the pepper spray. After unzipping the tent, our rude awakening turned out to be a spotted hyena, standing so close we could count every one of its spots.

I knew we had to chase it off immediately. Besides attracting more attention from other animals, it would certainly try to get into our food rations. With a big baboon-like bark, I lunged out of the tent, throwing stones and making a noise. The hyena would run a few metres and then stop, turn around and look at me. I eventually chased it so far away that I could no longer see the tent … at which point I realised that I was barefoot and running around in only my underwear.

We heard it all night long but it never returned to our camp. Almost every night thereafter, for three weeks, we heard hyenas and lions and were even visited by elephants one evening at Palmwag.

They used backpacks for the first leg in SA, then switched to a cart in Namibia, when they needed to carry more food and water.

We walked between 24 and 38 kilometres a day, taking one day off every week to rest. At times we carried up to 50 litres of water on our cart and a month’s supply of food. We would usually camp wherever we stopped for the night, unless we were offered a place to stay by the local farmers. Although the landscapes constantly changed, the friendliness of the people never did.

‘Sandshoes’ made from plastic picked up on the beach stopped their feet from sinking into the sand.

Near Kleinsee, this little koggelmander (agama lizard) thought hiding in the shade of Lauren’s skirt would keep it safe.

The word ‘adventure’ implies the unexpected. This walk was no exception. We had our fair share of setbacks, not least having to alter our coastal route to an inland one; I also had a camera stolen, and we had to contend with intense heat (our journey had been delayed by five months when Lauren got tendonitis in her foot, forcing us to set off in summer). Our cart also broke twice, but both times we happened to meet amazing guys who had just the right tools to help us (even in the middle of the Namib). There were many days when I seriously doubted what we were doing. In those moments,

I asked myself if we could give just one more step. The answer was always yes.

Bully beef and cheese for breakfast – a high-fat diet delivers a more steady supply of energy.

Reaching the magnificent Epupa Falls marked the end of 157 days of walking. But we felt strangely forlorn. All of a sudden our goal, our reason for waking up each morning, had been accomplished. The wind was taken out of our sails. ‘The journey is the destination’ definitely rang true for us.

How they did it:

Camping

Namibia is full of thorns, so we used closed-cell sleeping mats because they can’t get punctured. We placed them under our tent to preserve the tent base.

Camping chairs were essential. The ground is often too hot to sit on, and insects on the ground can be a nuisance.

Solar is the most reliable source of electricity in Namibia. We used a lightweight Goal Zero panel, battery and inverter. A small, cheap laptop and two external hard drives ensured that our photos and film footage were always backed up.

We never made a fire; all our food could be eaten without being cooked. It takes time and energy to make a fire after a long day’s walk, and a hiking stove needs lots of fuel.

On hot nights when it was impossible to sleep, we wet towels or cloths and used them like a blanket. This works like air con and cools you off in no time.

Walking

Most hikers go for boots or trail-running shoes, but we wore Chaco sandals, which helped our feet stay dry and cool. They also last much longer on sand.

Long-sleeved shirts keep the sun off and create a larger surface for sweat to evaporate from, making them cooler than short sleeves.

Lauren chose to wear a skirt instead of shorts. It not only kept her cool but protected her legs from thorny bushes and kept prying eyes at bay.

When used correctly, trekking poles can save up to 30 per cent of a hiker’s energy. They also doubled as tent pegs in the sand and could be used as weapons, if needed.

Words and photographs by Erlo Brown