When Matthew Sterne heard that the oldest baobabs in South Africa were dying, he decided to visit the ancients still standing. His baobab trail ended up being as surprising as it was unusual.

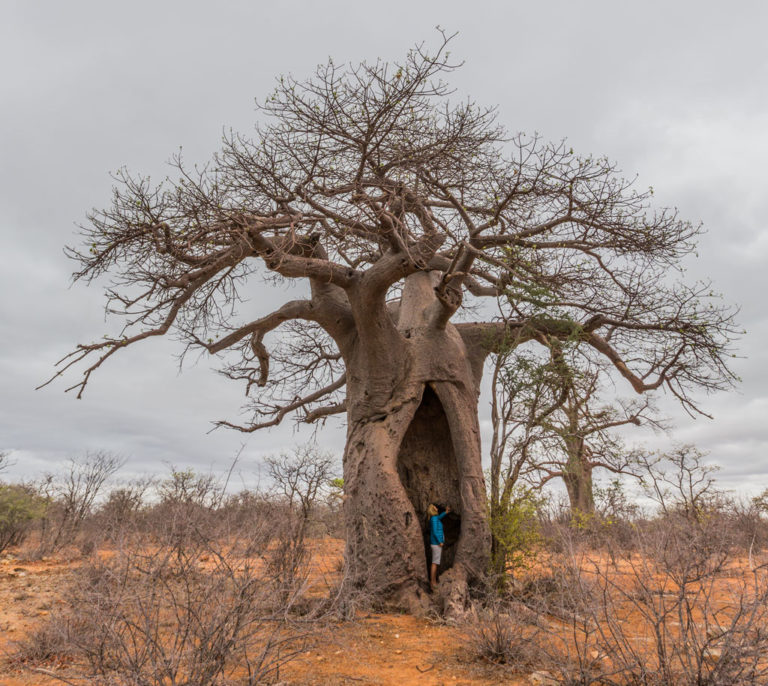

Sagole Baobab in Limpopo is the biggest of its kind in the world and is estimated to be around 1 200 years old. It already had a few centuries under its gaze when the kingdoms of Mapungubwe and Thulamela rose and fell.

It’s twice as big as any other of its kind in the region and looks as if someone took six massive trees and welded them together to form a super baobab. The bark is like ancient lava, melted and warped from centuries of African sun. It’s 22 metres high and

46 metres in circumference, making it the second-thickest tree in the world, after a cypress in Mexico, and requires at least 20 people to fully embrace it.

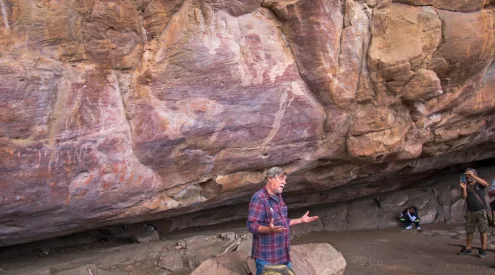

There’s just my mother and me here in Venda in Limpopo, and the conditions – low clouds, no wind, only the occasional bird call – create an air of intimacy. It feels like a private meeting with a 1 200-year-old celebrity. Like great bodies of water, the tree has a calming presence. We’ve been here for two hours circling, touching and climbing it, walking away for a different perspective and then up close again to feel its waxy bark and peer inside its cavernous hollow, where the world’s biggest colony of mottled spinetails resides. Normal colonies of these swifts number around 20; here there are 300. The birds gather in the sky every evening before entering for the night while bats leave through the same opening.

One of its branches reaches down to the orange earth, like a divine hand granting access to its elevated world, from where people have clambered up it for generations. It’s the kind of tree I dreamt about as a child – bigger than you could possibly imagine, a companion to animals and possessor of a great name. It’s called Sagole, but in Venda they call it Muri Kungulwa – The Tree that Roars.

The Swartwater Baobab is one of the Champion Trees of South Africa and one of the five biggest baobabs in the country. We found cattle resting in its shade.

Sagole is just one stop of many on our road trip to visit the biggest and best baobabs in the land. The idea was sparked by news that the oldest ones were under threat. Publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian and National Geographic had run alarming stories about their possible demise and how scientists were stumped. The coverage stemmed from a study by a Romanian professor, Adrian Patrut, and his colleagues who used radiocarbon dating to analyse more than 60 of the biggest and oldest baobabs in Africa to find out how they grow so large.

To their surprise, they found that since 2005, eight of the 13 oldest, and five of the six largest baobabs have either died or partially collapsed. These include well-known trees such as the Sunland Baobab (famous for the pub inside it), a gigantic specimen in Namibia called Grootboom and Botswana’s Chapman Baobab. Climate change was identified as the likely culprit and dendrophiles around the world panicked.

The concern was understandable. More than the lion, elephant or fish eagle, more than the Serengeti, Nile or Kilimanjaro, the baobab best represents Africa. It’s ancient, resilient, revered and adaptable. It thrives where other plants wither and die. These icons of the African savannah hold a power over our imagination. Reaching such unimaginable ages, they’re steeped in mystique, surrounded by superstition and seen as a way to communicate with the ancestors. In West Africa, prominent trees even receive special funerals.

The Land Rover Discovery 5 handled Musina Nature Reserve’s diabolical roads in comfort, with the necessary high clearance.

The more you learn about baobabs, the more fascinating they become. Their fruit can stay ripe for 10 years and the trees can produce fruit for 1 000, yet the flowers bloom for just one day. They’re the world’s largest succulents and can hold up to 4 500 litres of water. The baobab’s array of uses (more than 300) is legendary. The leaves can be boiled and eaten like spinach, while the seeds can be roasted like coffee. The fruit has six times more vitamin C than oranges, and three times more potassium than bananas. It’s been hailed as the ultimate superfruit and its powder is now stocked in Walmart in the USA and Boots in the United Kingdom.

The first thing I needed to know before setting out was: where are our biggest baobabs? I contacted Izak van der Merwe, a coordinator in the Department of Forestry and creator of a registry called The Champion Trees of South Africa. It’s a list of protected trees of cultural and historical significance – and ones that are just plain big. Of the 80 on the list, five of them are baobabs. And they’re all in Limpopo.

Izak mentioned in an email that, in addition to the listed trees, there was a baobab in Honnet Nature Reserve near Tshipise that he was very excited about. ‘Although we still have to confirm measurements, we suspect from the photos that it’s likely to be the second-largest baobab in South Africa after Sagole, and possibly the third-thickest tree in the world,’ he wrote. Possibly the third-thickest tree in the world? Still to be confirmed? The idea that an unverified giant was waiting to be revealed in Limpopo was too enticing to resist. I added the reserve to my route and set off with the hope of unveiling a colossus.

In Venda, baobabs line the road, acting as bus stops, shelters and kiosks.

So, I had a route and a quest. All I needed was a decent sidekick. Someone who could manage the snacks, handle the navigation and know not to talk to me when I grew sleepy (and slightly grumpy) in the afternoon. My mother, a recently retired school teacher, was the ideal candidate. The navigation was a potential point of conflict, especially considering my mom’s technological capabilities. But it also seemed like a small way to return the favour for all the holidays we’d been on when I was a child, the bonus of having a teacher for a parent. My mom had taken my sisters and me on plenty of train trips to Joburg, Garden Route sojourns and Karoo road trips. Now it could be her turn to sit back and ask, ‘Are we there yet?’

We left Joburg early on a Monday morning in our chosen vehicle, the impressive Land Rover Discovery 5, aiming for the Soutpansberg, where baobab country begins and extends north into 30 other countries. Our first stop was the famous Glencoe tree, on a lucerne farm just outside Hoedspruit. It’s the oldest-known African baobab in the world.

Once the tree had a circumference of 47 metres but it split twice in 2009 and collapsed completely in 2017, yet still lives on. Viewed from a distance, it looks like a small wood, but if you step inside its dome of foliage you see it for what it is, a labyrinth of fibres and trunks splayed on the ground. An information board nearby states, ‘This magnificent upside down tree can be described as a grizzled, distorted old goblin. With the girth of a giant, the hide of a rhinoceros, [and] twiggy fingers clutching at empty air.’

The Leydsdorp Baobab was used as a cool room for many years as its inside temperature is a cool 22°C

I got chatting to Sharon Liversage, who runs the pancake restaurant next to the tree. She told us that when Paul Kruger came this way with his ox wagons, he moved from baobab to baobab. ‘A few years ago, some people arrived in a helicopter and asked if we wanted to sell the farm,’ she said. ‘Their oupa had one half of a map that suggested the Kruger gold was buried on the farm near this tree. They’re convinced it’s here and spent two weeks with diviners looking for it, but found nothing.’

We continued north, bound for two other big baobabs, passing mango sellers and sad-looking donkeys standing in the shade of trees as if waiting for the bus. The Leydsdorp Baobab has a slight lean and looks like it’s covered in braille from all the old, buckled graffiti. A retired policeman, Swanie Swanepoel, acts as its guardian on a game farm. He pointed out a spotted eagle-owl in its branches. ‘This is the best pension job in the country,’ he said.

We found the leafy King-of-Garatjeke towering above a dusty rural village in Modjadjiskloof. Under it, a gathering of young men were betting on a game of dice; goats and chickens pecked at its base while small boys lounged against it. ‘Now this is a working baobab,’ my mom said. Like so many upside-down trees, the King-of-Garatjeke acts as a kind of town hall. Across Africa, they’ve also doubled as prisons, pubs, post offices, gun safes, cool rooms, treehouses and one, in the Caprivi Strip, even held a flush toilet.

The King-of-Garatjeke presides over many a social gathering in Modjadjiskloof.

We spent the night in Louis Trichardt, where we met up with Sarah Venter. She did her PhD on the ecology of baobabs and owns a company that sustainably harvests the fruit. I asked her about the plight of the oldest trees. ‘Only four of them have actually died. Some of the others have collapsed but that’s normal behaviour, they can carry on growing for hundreds of years,’ she said. ‘Those articles you read were pretty sensational and misinterpreted by many news outlets. I wouldn’t be too worried about the older population. What’s more concerning is the lack of a younger generation due to overgrazing of the seedlings by goats and other herbivores,’ she said.

The trees, however, might be able to overcome this. ‘When conditions are right – after good rainfall, or when there are fewer browsers after an anthrax outbreak – germinating seedlings will survive and establish a new generation of baobab trees,’ said Sarah to the chorus of bushveld night sounds. ‘That’s known as episodic recruitment and is the reason you see many baobabs of a similar size in one area.’

South Africa’s answer to Madagascar’s Avenue of Baobabs

Next morning, we headed for Pafuri Gate in northern Kruger. As soon as we crossed the Soutpansberg, we were in baobab country proper. After counting mere individuals on our first day, we now saw 10 at a time. Every rest area had one looming over it, providing shade and marking the route. In villages, the baobabs presided over kraals, bus stops, spaza shops, watermelon vendors and schools. One rest area had more than 20 trees huddled together like a herd of elephants.

On a whim, we took a sandy side road and found a small forest with an array of the odd-shaped baobabs. Some had green leaves and white flowers while others were completely bare. They varied from low and squat to tall and majestic. A few were as bent and bloated as homegrown sweet potatoes; others looked like botched attempts at glass blowing. I was reminded of the Avenue of the Baobabs, a striking group of trees lining a dirt road in Madagascar. This must be South Africa’s version, I thought. After a couple of hours of exploring the potholed, baobab-heavy road, we reached Sagole, the monster of the mopane veld. My mom said, ‘Wow!’ twice before we’d even got out the car.

We found more baobabs in the Kruger’s Pafuri section, and even more in Musina Nature Reserve, formerly known as Messina Baobab Forest Reserve, proclaimed in 1926 specifically to protect its trees. This was all just a forerunner to the main event, though, because next up was Honnet Nature Reserve, where my slumbering giant was waiting.

One of the stranger baobab shapes we encountered

Francois Bosman, the eco manager of the Tshipise holiday resort, drove us in a game vehicle to the tree, six kilometres from the camp. As we approached it, my heart sank a little. It was a beautiful specimen with a stout base and branches so strong and crisp they looked like granite … but nowhere near the size of Sagole. I took the measurements (22 metres around, 13 metres high) and sent them to Sarah via my phone. ‘It’s a big one, but not a giant,’ she wrote, followed by some or other emoji that did nothing to soothe my disappointment.

Of all the gigantic and gnarled trees we’d seen, we were yet to come across a baobab of historical significance. So we crossed the Botswana border into Mashatu Game Reserve in the Tuli Block, after visiting the elephant-damaged trees of Mapungubwe. Like Baines, Chapman and Livingstone, Cecil John Rhodes also had a baobab named after him. The empire builder was there in the 1890s while plotting a route for his proposed Cape to Cairo railway and carved his initials in a tree on the edge of a rocky promontory.

‘But it’s not his baobab,’ said our guide, Bellamy Noko. ‘The local people were here way before he came this way. We call it the Mmamagwa Baobab after the archaeological site dating back to the 11th century, which is found on the same sandstone hill.’

We saw 16 big cats on just one morning in Mashatu, including this leopard with an impala kill nearby.

We arrived an hour before sunset and watched as elephants trudged up a nearby escarpment. The hill was surrounded by a few other golden sandstone koppies and had a panoramic view of the sparse grassland below. Most visitors agree there’s a certain magic to the place and it must be one of the best sunset spots in Africa. I put my arm around my mom and clinked her cold gin and tonic. Mmamagwa stood over us, looking glorious in the last rays of the day. Just as it has done for centuries, and hopefully will do for many years to come.

The arboreal behemoths had been the main attraction on our trip but they weren’t the only one. We had criss-crossed Limpopo from the fever-tree forest near Crooks Corner to Mapungubwe and beyond – and searching for giant baobabs had added a quest element. We had journeyed to parts of our country we’d likely have never visited otherwise, places such as Modjadjiskloof, Leydsdorp and Alldays. And we’d met engaging bushveld characters like Swanie, Sarah, Francois and Bellamy. Every day was full, long and came with pleasant surprises – from finding a hot spring in Tshipise to soak our tired bodies in, listening to a group of toddlers in Zwigodini sing for us, or spending half an hour with a leopard in Mashatu. It was as if the enchantment of these remarkable trees had imbued our trip with a similar charm. And now my mother and I could reminisce about one more trip together.

The Mmamagwa Baobab in Botswana’s Mashatu Game Reserve juts out of a sandstone koppie like a rhino horn.

Giant Baobabs

Glencoe Baobab – Some 1 853 years old and lying on its back, this tree continues to sprout shoots from its branches. There’s a beautiful 500-year-old baobab nearby that most visitors assume to be the tree.

Leydsdorp Baobab – Halfway between Tzaneen and Hoedspruit, the Leydsdorp Baobab is named after a former gold-rush town. Swanie Swanepoel will give you a tour and sell you a cold drink if you’re thirsty. Entrance is R10.

King-of-Garatjeke – This was the trickiest baobab to find. We followed Google Maps to Garatseke Primary School (the spelling was wrong but we took a chance) on a bumpy dirt road and found this massive tree in the centre of the village.

Sunland Baobab – South Africa’s famous baobab pub is unfortunately out of commission after collapsing in 2017. The tree was 46 metres in circumference and had a wine cellar and draught beer on tap. The record for the number of people in the bar was 56.

Sagole Baobab – Managed by the local community, the world’s biggest baobab lies near the Venda town of Zwigodini. Entrance is R30 and it’s open from 8am to 4pm daily. If you’d like to stay to see the mottled spinetails return to the tree it costs R300.

Swartwater Baobab – The last of the Champion Trees we visited, this beautiful specimen is on a cattle farm just outside the small town of Swartwater. The roads in this region are terrible so drive carefully. The tree stands 500 metres off a side road behind

a cattle gate.

Musina Nature Reserve in the Soutpansberg Region has one of the largest collections of baobabs in the country, and incorporates the former Baobab Forest Reserve – formed in 1926 to protect the baobabs from commercial interests.

Directory

The Baobab Restaurant This eatery overlooks the Glencoe tree and specialises in pancakes. Try a cinnamon and sugar (R25), venison (R60) or banana-and-caramel (R50) treat. 0823327887

Zvakanaka Farm Just outside Louis Trichardt, Zvakanaka has secluded cottages and a campsite. We stayed in Madala’s Cottage, which has an outside bath, pool and indoor fireplace. Birds are abundant and the hosts are lovely. Camp for R150 per person; cottages cost R425 per person. 0844004595, zka.co.za

Pafuri Section, Kruger National Park There are some impressive baobabs between the Pafuri Gate and the Luvuvhu River. Park entry is R93 per person; there’s a shop, restaurant and petrol station at Punda Maria Rest Camp, 76km from the gate. Campsites from R243 per person (max six) and bungalows from R370 per person. sanparks.org

Pafuri River Camp Lantern-lit tents on stilts create a classic safari-camp feel under the trees, just 10 minutes drive from Pafuri Gate. Guests can enjoy a catered braai every evening in the lapa, which has a pool and bar. Camping is R175 per person and self-catering tents cost R570 per person sharing. 0827850305, pafuri.co.za

Tshipise A Forever Resort Built in the 1930s around the hot spring, it has 95 chalets, 370 campsites, a butchery, shop, restaurant and hot-spring pools. Chalets with a patio and braai area from R1 800 (sleeps four), camping is R170 a site plus R70 per person. 0155390634, forevertshipise.co.za

Musina Nature Reserve You’ll need a high-clearance 4×4 for the notoriously bad 22km road. Clumps of baobabs appear throughout the reserve, which borders the Sand River and has plains game such as giraffe and wildebeest. Entrance is R35 a vehicle, R25 for adults, R20 for children. 0155343235

Mapungubwe National Park Apart from its famous archaeological site and wildlife, Mapungubwe is also home to baobabs, although many have been badly damaged by elephants. ‘It’s part of nature, we leave it,’ a ranger told me. Park entry is R55 per person; camp- sites from R303 (for six people) and cottages from R345 per person. sanparks.org, 0155347923

Mashatu Lodge Cross-border Mashatu Game Reserve is often called the predator capital of Botswana, and our experience there suggests it’s a fair claim. The lodge rooms are large and luxurious, the food is top notch and the guides are excellent. R8,525 per person full board. 0317613440 mashatu.com

About the car

Land Rover’s latest Discovery 5 took all terrain challenges in its stride and was a pleasure to drive on highways. The pre-programmable drivetrain allows off-road novices to set optimum driving with a simple turn of a controller in the centre console. landrover.co.za