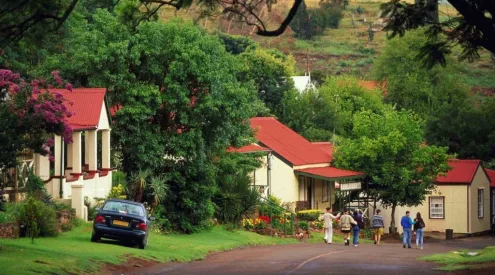

Zambian farmers like this woman are growing tabasco chillies to deter elephants. Image credit: Conservation South Luangwa

When elephants gobbled up Donald Banda’s crop of maize, ‘We had hunger as a family,’ he says. School books became unaffordable, as did school fees. But now Donald patrols the fields around his village, armed with a ‘blaster’ that fires a secret weapon: ping-pong balls filled with chilli oil. ‘Elephants run away, unless I miss the target,’ he reports.

Donald is one of 30 volunteers who have joined forces with Conservation South Luangwa (CSL) to prevent elephants raiding crops and thus improve human-wildlife relations in this increasingly populated area. They patrol night and day, or man duty posts (small wooden watch- towers). The chilli bombs are aimed at the rear end of the elephant, so that when it touches this area with its trunk, the oil irritates its trunk and eyes.

‘It’s a non-lethal intervention,’ says Adrian Coley of Flatdogs Camp, one of the project’s donors. ‘It started by putting chilli grease on fences, which they’d sniff with their trunks and then go away. But they got clever and used to back into the fences and knock them down.’

The blasters are fired by lighting a chamber filled with flammable insect spray, which launches the ping-pong balls with loud bangs. CSL states that with the help of other methods such as burning chilli bricks and building elephant-proof storage houses for grain, about 3 000 incursions have been avoided since the project began in 2013.

Villagers grow the tabasco chillies (Capsicum frutescens) needed for the bombs. They sell these to CSL, which then also supplies chilli-sauce makers in Lusaka. Last year, 162 farmers in the Kakumbi chiefdom harvested over 10 000 kilogrammes of chilli and sold it for $15 000 (R213 000). Some have even moved away from growing subsistence maize and rice crops in favour of chillies.

Volunteer patrollers carry the chilli blasters that keep local ellies away from crops without hurting them. Image credit: Conservation South Luangwa

Donald is just one beneficiary. ‘I can now pay school fees for my children and buy books, pens and pencils,’ he says. ‘My parents are benefitting from money to buy grinding meal and soap, and I am able to buy other groceries.’ The elephants, meanwhile, are less likely to be injured by irate villagers. Here’s to peace – and chilli sauce.

*Help CSL make more blasters, solve human-wildlife conflict, or fund more volunteers and education projects via cslzambia.org/get-involved.

Copper vs Tourism

It’s a battle that’s been smouldering for nearly a decade. Reports of an opencast copper mine in Zambia’s Lower Zambezi National Park emerged around 2011 when an Australian company won prospecting rights. The 4,092-square-kilometre wilderness area, across the river from Mana Pools in Zimbabwe, is an important wildlife refuge and corridor. WWF Zambia reckons that the mine could spell the loss of 50 per cent or ‘the entire northern part’ of the park.

In October 2019, the Zambian High Court ruled that the Kangaluwi Copper Project could go ahead. Cue an outcry: even former president Kenneth Kaunda weighed in, saying this was ‘the biggest threat in history to the wildlife and pristine wilderness’. Government backtracked – but by mid-December, no official statement ditching the mine had been issued.

Also, ‘We understand there are other applications for further exploration licences in the Lower Zambezi National Park,’ says Ian Stevenson, CEO of Conservation Lower Zambezi. The park supports a significant elephant population in the region. Tourism employs ‘more than 1,000 locals’ and wages estimated at $4 million (about R56 million) benefit many more each year. If the Zambezi River becomes polluted, subsistence fishing could also be threatened. ‘Sustainability from wildlife and the tourism sector is long term, compared to the potentially unviable mineral deposits and the unknown length of the proposed mine or mines,’ says Ian. conservationlowerzambezi.org

Words: Janine Stephen