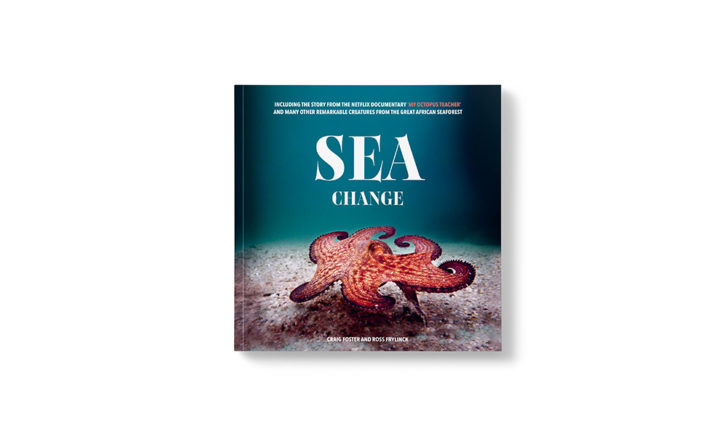

By exploring the African sea forests for nearly a decade, a small group of pioneers have given us a new understanding of life on the coastline and a groundbreaking film My Octopus Teacher. The book Sea Change tells the story of this undersea environment and reveals the remarkable creatures that they encounter every day.

Photos: Sea Change Project

It’s important to learn to respect the ocean but not fear it. Fear is often associated with not knowing animal behaviour. This compass jellyfish, with its bright colours, is pretending to be harmful but it’s harmless to humans. It is only able to sting small prey.

Introduction by Anton Crone

One of my greatest teachers wasn’t the octopus, it was the octopus’ pupil, Craig Foster. Five years ago he invited me for a swim that changed the way I looked at the world. At the time, Craig was in the middle of his transformative experiment to dive the cold waters of False Bay’s sea forest every single day. What he learnt was astounding. You’re likely to have seen a good deal of it in the film My Octopus Teacher which has captivated audiences worldwide. And he learnt much more, like the art of tracking animals underwater and how our ancestors hunted them; he discovered new species and documented astounding behaviour never before seen; Craig – along with Ross Frylinck, Pippa Erlich and the team of the Sea Change Project – became disciples of cold, revelling in the mental and physical benefits of cold water immersion and the tranquility of the aquatic world. Divers ensconced in wetsuits and scuba gear would often emerge shivering from the ocean only to be passed by a tribe of happy free divers on their way into the chilly domain wearing nothing but shorts or bikinis.

This trap limpet is waiting to slam down on a kelp frond as it washes under its shell, in order to feed.

When he first invited me into this world, my mind and body rebelled. My imagination shrank at first to focus exclusively on the cold, then it soon expanded beyond the proportions I was used to. Craig helped me appreciate the transformation that occurs when we hold our breath and our bodies are immersed in cold water. Everything is fast-tracked, our vulnerability becomes acute and our senses are heightened. I recognised this swimming through the forest, pulling myself down on long kelp stems to reach the sea bed, holding my breath for longer and longer as I dived deeper and deeper. The reward was a clarity of vision and a profound appreciation of the wildlife surrounding me, that accepted me without fear or favour. I often return to this environment, and I hope we can give you a taste of it among these pages, and perhaps invite you into a new world.

This blue dragon or sea swallow lives by floating on the open ocean, eating bluebottles and storing their stinging cells in its own body to repel predators.

The blue button lives on the surface of the sea. It comprises a round, flat float and a ring of ‘tentacles’ that are actually a colony of hydroids. The tentacles are fragile and easily break off when the button is washed ashore, and it’s rare to see a fully intact animal like this one.

There are at least 24 species of klipvis found only in South Africa’s kelp forests. The nose-stripe klipvis lives in the intertidal zone and can survive for hours out of water as long as it stays damp. The king of the bunch is the super klipvis. These bold, charismatic fish followed us around the forest and are the worst photo-bombers. They are often seen trailing after an octopus, waiting for small animals flushed by the octopus while it is hunting or building a den. Sometimes an octopus will catch and eat one but mostly they are seen biting the end of an octopus’ arm or harassing it if it has caught prey.

Craig Foster is an award-winning filmmaker and avid naturalist. His filmmaking career has spanned three decades and he has received more than 60 international awards, including the Golden Panda, the ‘Oscar’ of natural history filmmaking. He grew up foraging and diving on the Cape Peninsula and for the past eight years he has pledged to dive in the kelp forest 365 times a year. Craig has worked closely with some of the world’s top kelp forest biologists, archaeologists, anthropologists and San rock art experts.

These pair of rocksuckers were behaving strangely. They were shuffling up to one another, moving on their suction pads. They bumped each other’s bodies and then one of them changed colour, from dark brown to bright light yellow. After a few hours, this rocksucker started laying eggs. The strange behaviour must have been a courtship dance, never recorded before.

This image was taken from below, looking up to the surface. The animal is a globular bubble raft shell. It has evolved from a bottom-dwelling snail called a wentletrap, which still exists today. Bubble rafters live at the top of the open ocean, suspended from a stream of bubbles they create themselves and which harden into a stiff raft. This particular species broods its young on the raft. The change in colour of the eggs shows how the ones laid first have become darker and are more developed than the newly laid pink ones.

My Octopus Teacher co-director, Pippa Ehrlich, has been telling stories about nature, science and conservation for 10 years as a journalist and filmmaker. She has worked with top marine scientists and under-water photographers around the world and has been free-diving in Cape Town’s sea forest for a decade. More recently, she gave up her wetsuit and started skin-diving almost every day. Pippa is currently editing and co-directing a kelp forest feature documentary combining natural history with indigenous philosophy and wilderness psych-ology to explore the bond between humans and the natural world.

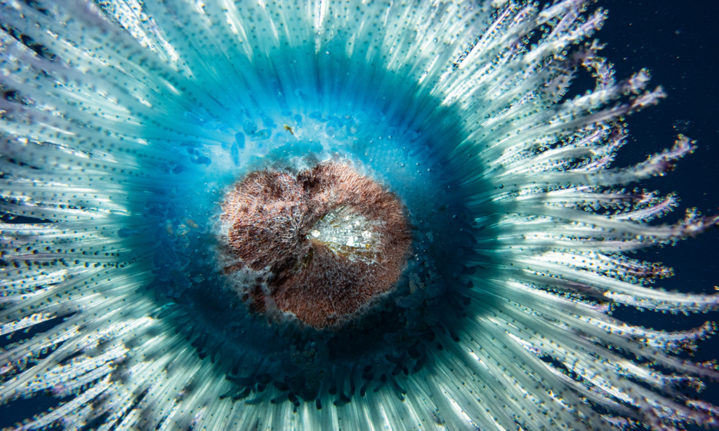

It’s possible to track what a young abalone has eaten by looking at the colour pattern on its shell. A very rare case in nature, this animal has kept changing its diet from bacteria and algal sporelings to kelp and back again. The red is associated with microbial film and the blue with kelp. Like rings in tree trunks, these growth patterns can provide detailed information about an animal’s life: its diet and the water temperature it lived in. If it’s a very old shell, even part of the ancient climate at the time when the animal was alive can be reconstructed.

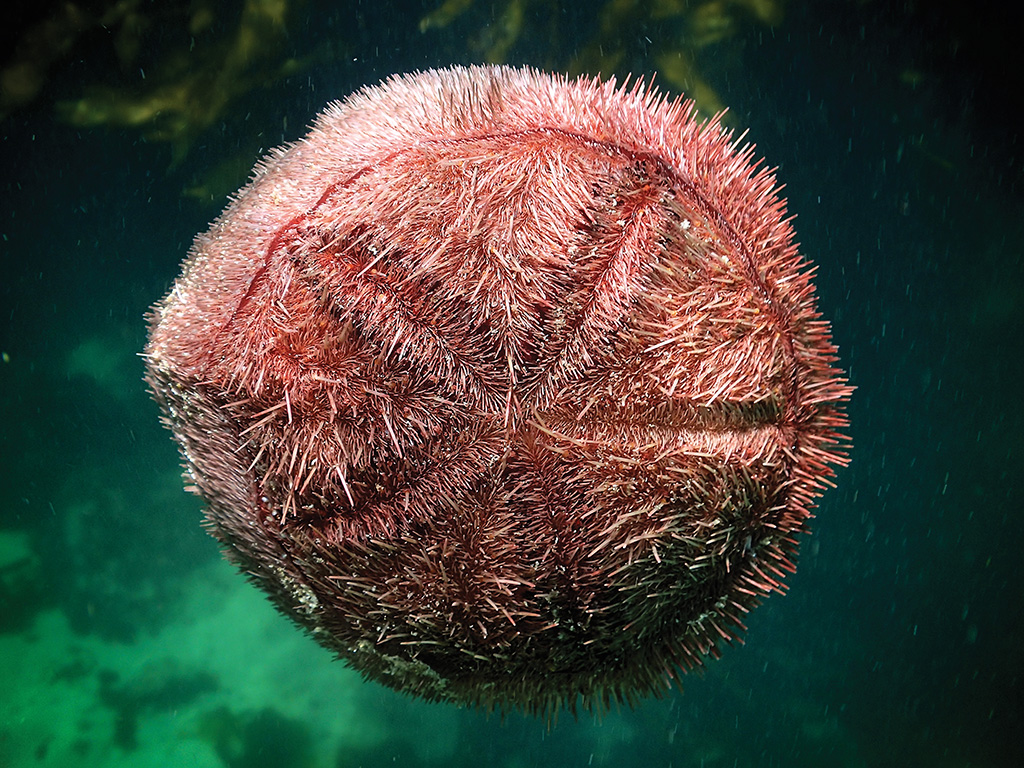

Heart urchins are some of the most cryptic of sea forest creatures, lying hidden in burrows in the gravelly sand. These burrows act as detritus traps, catching small particles of mostly kelp. The urchins essentially eat sand, analysing particles with specialised organs before ingesting them. Most of the shell is filled by a metre-long tube of stomach, which extracts nutrients from the sand.

Ross Frylinck has been exploring the South African coastline as a surfer and free-diver for most of his life. He started the Wavescape Ocean Festival and has been pioneering ocean conservation and culture in South Africa for the past 15 years. Once a commissioning editor for Cambridge University Press, he has been telling stories about the sea since his first school essay.

Argonauts are essentially ancient octopuses that have sailed the open seas since before the dinosaurs came into existence. Only the female has a beautiful shell. She gulps air from the surface and keeps just enough air in her shell to maintain neutral buoyancy. The male is much smaller, 600 times lighter than the female, and does not have a shell.

A classic scene of a pregnant agile klipvis resting in a giant limpet shell. (All captions by Craig Foster)

These images and over 240 others are published in Sea Change. This stunning book takes you on an evocative journey into the secret life of the Southern African Kelp Forest where Craig and Ross spent eight years exploring together, diving almost every day. This is the story of what they found in the wild, and how it has transformed their lives.

seachangeproject.com

‘A magnificent book’ – Sir David Attenborough

Price: R395

Quivertree Publications