It has been 35 years since the Quagga Project’s inception after conclusive DNA evidence proved that the quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra. The programme is now starting to produce offspring with reduced striping, but it is still far from complete.

READ: Can the quagga be resurrected? Part I: The origin story

After historian Reinhold Rau’s persistent and meticulous efforts, the Quagga Project was born. Initiated by a group of dedicated individuals, they embarked on the ambitious task of bringing an animal back from extinction and hopefully, to the wild.

Is extinction final?

The successful DNA sequencing of the quagga might have inspired Michael Crichton to write Jurassic Park, but we still won’t be seeing the dodo or a prehistoric reptile anytime soon. The reason the quagga is an exception, is that it was not a separate species as many initially thought.

Picture: The Quagga Project

With the quagga only a subspecies of the diverse plains zebra, those visual characteristics could still be out there in the existent population, scattered among herds roaming anywhere from Etosha to Zululand. More than half a million plain zebras are running around, and this project sought to find the right ones.

This is not cloning, but a purely selective breeding programme. Plains zebra were scrutinously selected based on their reduced striping and brown tints. The original formation herd consisted of nine zebra captured in Etosha National Park, Namibia in 1987 and relocated to a conservation farm near Robertson, with the first foal being born in December 1988.

Over the years, further breeding stock was added from Zululand, with the project expanding their numbers and the land. The project is currently between its fifth and sixth generations, and several young animals are now appearing to be visually closer to a quagga than a typical plains zebra.

This is promising, and quite an achievement when you consider how far the project has progressed in 25 years. But if these specific subspecies are long gone, how can scientists be sure that the offspring born are indeed quagga?

Grading Rau’s quagga

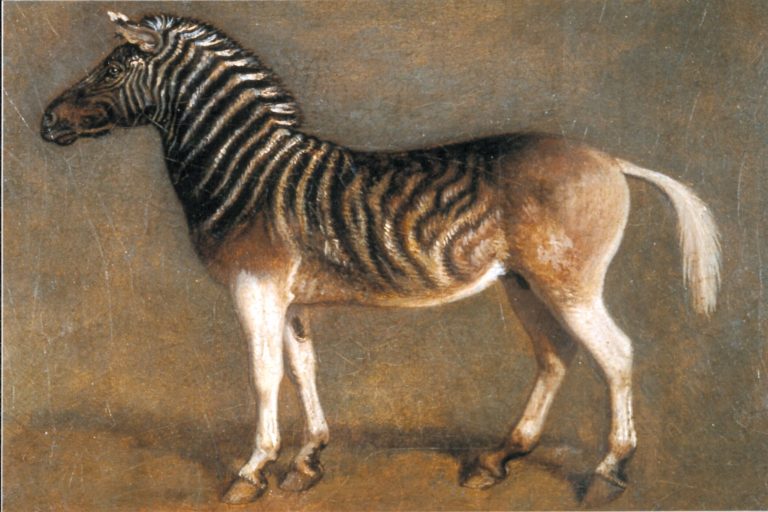

Firstly, it is important to note that this is not a traditional quagga, but a Rau’s quagga, named after Reinhold Rau because of its different genetic route. But based on the evidence of preserved quagga skins, there was a great deal of variation among the quagga population, making it difficult to pinpoint a definitive quagga.

Only portions of the quagga’s DNA are known (enough to conclusively say it’s a plains zebra), and since the coat pattern was the only criteria for determining a quagga, rebred animals with the same visual characteristics can justifiably be called quaggas.

So then how is a quagga gauged? There is enough evidence from preserved quagga skins as well as portraits commissioned by renowned painters to work with. When the breeding project began in 1987, a meticulous grading system was implemented.

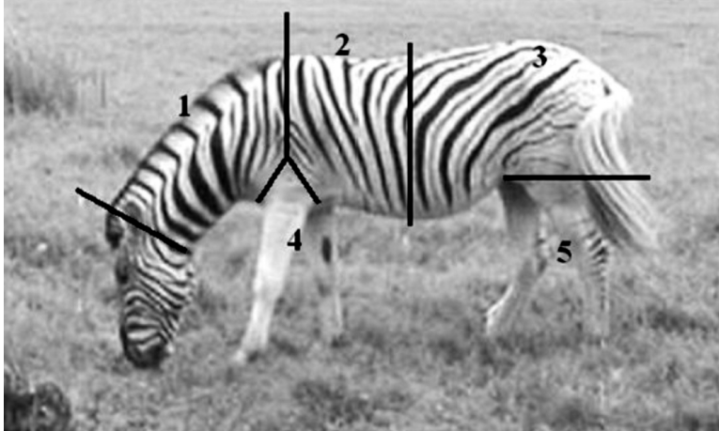

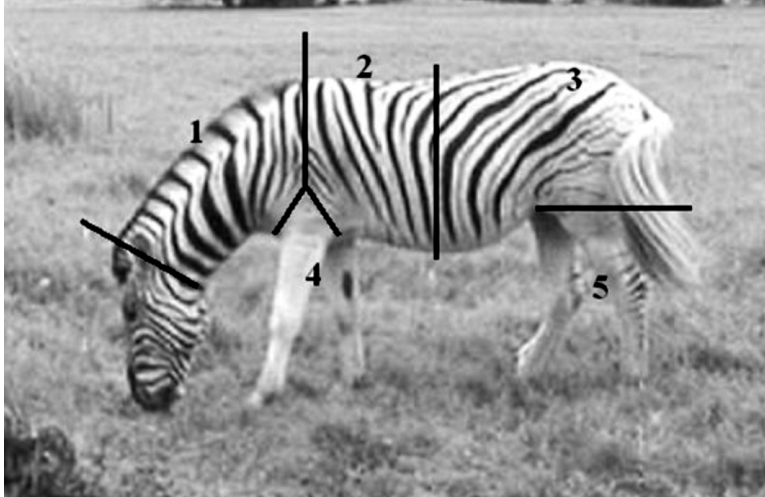

The grading system involves dividing the body into five parts and counting all the stripes on the body. The important part is the reduced striping on the hind legs and the rear of the body. A general rule is that if the animal has no scorable stripes on the hind of the body and no stripes on the legs, it qualifies as a Rau’s quagga.

The Quagga is divided into five sections and each stripe is counted to determine if it meets the criteria. Picture: The Quagga Project

‘Two basic things that needed to be done: we needed to reduce the striping quite fundamentally and you need to increase a brown chestnut background. Your classic quagga is very brown, clean white legs, white tummy, but heavily striped on the neck but the brown goes all the way,’ project coordinator, March Turnbull said.

‘In a nutshell, getting rid of the stripes is doable. getting the brown is a struggle. it’s coming slowly. it’s within the animal,’ Turnbull added. ‘it’s maddening because I now look at every zebra in the bush,’ always keeping an eye out for the perfect specimen.

‘We learnt by the third generation we can breed the stripes away,’ says Bernard Wooding, conservation manager of the project and Elandsberg farms, home to a herd of Rau’s quagga.

Now in its fifth to sixth generation, the focus is shifting to getting that brown. There is now a complete overhaul of their grading system, where they are already observing different grades of brown on the animal’s body – the rump, hind legs and so forth.

‘We must consider if we should report those grades independently for each animal, or blend them to give a composite or aggregate grading,’ Turnbull commented.

How close are we to having Rau’s quagga on our hands?

Nina, one of the promising Rau’s quagga specimens. Picture: The Quagga Project.

‘I can’t really say when. Records suggest that there was a tremendous variety of pelage within historical quagga populations,’ Turnbull said. ‘Our rule of thumb is that an animal would qualify if it would be unremarkable to an observer when dropped into a herd of 19th-century quaggas.’

Wooding believes that some of the animals can already pass that test, but remains patient: ‘It’s a fun project, we can wait 10 years.’

Nina with her foal.

When on a game drive with Bernard at the Elandberg herd near Wellington, he pointed out Nina with one of her recent foals. ‘Nina is a fairly brown one, and one of the stars of the project.’ There was much excitement when after nearly two years of waiting, she gave birth to a foal, demonstrating that the project is heading in the right direction.

The quagga after the project

This could still be some time far in the future, with Turnbull confessing that he thinks he might be passing on the baton to someone else. It should be noted that everyone is volunteering their time, and there is no financial incentive as the project navigates its way around limited funding all the while contributing significantly to a world-first scientific endeavour.

This project is a world-first for its kind, and the only comparable project being the rebreeding of the Floreana Island tortoise, a subspecies of the giant Galapagos tortoise. Their studies have uncovered much about the breeding habits of plains zebras in different settings.

When the project reaches the point where they have 40 Rau’s quagga that are likely to breed true, the Quagga Project hopes to release this herd into the wild, serving as a reminder of how far we’ve come, and to never make the same mistake of letting a species go extinct again.

Pictures: David Henning

ALSO READ

DNA study shows traces of shark meat in cat and dog food in Singapore