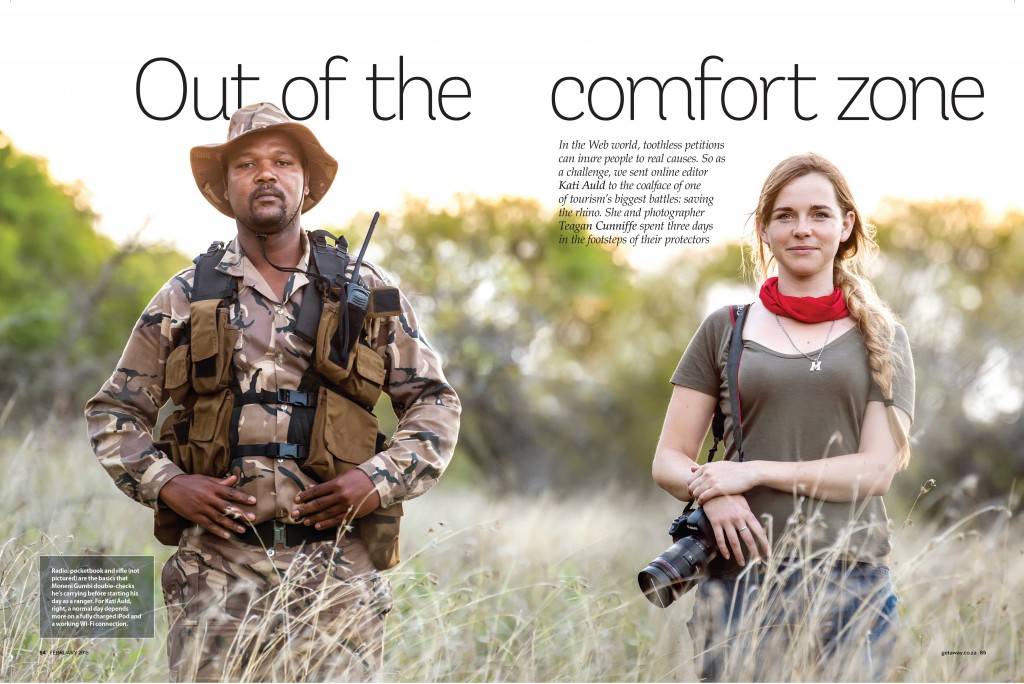

In the Web world, toothless petitions can inure people to real causes. So as a challenge, we sent online editor Kati Auld to the coal face of one of tourism’s biggest battles: saving the rhino. She and photographer Teagan Cunniffe spent three days in the footsteps of their protectors in Somkhanda Game Reserve.

See more: rhino tracking in Somkhanda

I’m tiptoeing up a dry riverbank, trying not to breathe too loudly. Early morning mist is hanging over the acacias, and all we know is that a group of three black rhinos is close. Really close. We’re peering through the thick brush, trying to isolate anything vaguely rhino-shaped, when a cheery jangle cuts through the still morning. Our companions stare in horror as I fish through my pockets to find and kill my cellphone’s alarm tone. Crud.

It’s 7am – the time I’d usually be rolling out of bed and blearily checking my newsfeed, but today I’ve been tracking rhino for two hours already. That’s what happens at Somkhanda Game Reserve – the only community-owned game reserve that’s home to both black and white rhino. It has come a long way since the reserve was returned to the local Gumbi community in 2006. The previous land-owners’ legacy was more than old farmhouses – a reputation for shooting animals from a 4×4 meant Somkhanda inherited skittish wildlife which bolted at the sound of an engine. In the eight short years since the land claim a lot has changed. Now nyala graze on the lawn outside the thatched cottages and warthogs snooze in the dappled sunlight next to the pool. There’s a pack of wild dogs roaming the farm, and plans for introducing lion in the next few years.

Sabelo Gumbi has been working at Somkhanda since 2012.

The quiet Somkhanda bush, set high above its noisier neighbour, Jozini Dam.

But back to the precious rhino. It’s people such as Sihle Mathe, one of Wildlife ACT’s newest recruits, who has the job of protecting them. With my disgraced cellphone now on silent, we’re tracking another group of rhinos. Sihle has a slight stutter and khaki socks up past his calves. He’s swinging the cross-hatch of an aerial in the air, combing for feedback from rhino foot collars. Every morning at 5am, he and the three rhino monitors bump along a precipitous 4×4 track that snakes through Somkhanda, keeping track of each rhino on the 12500 hilly hectares. The only traffic they’ll encounter on their way to work is a constant stream of noisy crested guineafowl. The foot collars can pinpoint a rhino within a few hundred metres, but in the thorny brush even something the size of rhino can be surprisingly hard to spot. Following (closely) in his footsteps is a rare privilege, but it’s not without its dangers – rhinos might seem lumbering but they can charge at speeds of up to 50 kilometres an hour.

Rhino poaching has always seemed like an isolated issue to me, floating in a miasma of shouty Facebook comments and massive corporate awareness campaigns. I’ll be honest, I’m more likely to give my R5 to a street busker than buy ‘Save the rhinos’ merchandise at my local supermarket. Being here, though, the links between the animals, the people and the land are growing roots in my mind. Large herbivorous mammals are only one aspect of the legacy that’s being protected at Somkhanda.

The reserve is rural enough that running water and electricity are recent developments. The Gumbi community numbers about 15000 people, spread out in scattered homesteads of round Zulu huts in bubblegum colours, supplemented by corrugated iron and facebrick. Most people here have never had formal employment and live off the land.

About 80 people from the community work at Somkhanda, from housekeeping to management to rangers. The model adopted by the Ezemvelo Trust – another roleplayer in the reserve – involves equipping people with skills and experience. Still, once people have gained the qualifications to move on to bigger or more prestigious reserves, they rarely do. That’s because people are invested in Somkhanda as more than a workplace – it’s home. Keeping the cogs of tourism turning is a personal matter.

Indeed, there are a lot of roleplayers involved in the project – from banks funding the rhino programme, to African Insight managing the lodge and restaurant. One of these is Wildlands Conservation Trust, which runs rhino conservation projects. Wildlands project manager Dave Gilroy is walking with me around the fresh squelch-marks of a notoriously shy rhino mother and calf. We’re talking about the likelihood of rhino horn trade being legalised, and he’s wrapping his words around the acacia thorn he’s chewing on. There are many intellectual debates to be had around rhino poaching and I, along with the entire internet, have an opinion on most of them. Armchair activism, mediated by a two-dimensional screen: that’s what I know. My academic musings are brought to earth abruptly when his phone chirps. It’s an update to the Somkhanda Whatsapp group – someone’s found an unfamiliar footprint near the perimeter fence. Intellectual debates suddenly seem inconsequential compared to the simple question: friend or foe? (It turned out to be guests.)

Sinister signs dot the fences, but do little to deter hardened poachers. Photo by Teagan Cunniffe.

Despite all the technological advances, Dave tells me, ‘it’s warm bodies that are going to win this war’. He’s not just talking about the rhino monitors. Their jobs aren’t without danger – everyone’s been treed by a cantankerous rhino at some point – but at least they don’t have to face rifles. That’s not the case for the other rhino guardians – the rangers.

Rumbling over the dirt tracks of Somkhanda, sharing the bakkie with a panga and a spare tyre, is everyday life for Moses.

Following in the footsteps of Sabelo and Moneni Gumbi, rangers at Somkhanda.

The next morning, against a brindle-pink sky, I’m tagging along on a patrol with Moneni Gumbi, who was born three kilometres from the gates of the reserve. He and his uncle Sabelo – who wears a gold chain and a don’t-mess-with-me expression – are two of the 20 rangers from the surrounding areas who’ve trained as African Foot Rangers and have a hand in protecting their own legacy on the front lines. The path winds along the electric fence, over rocks and long grass, skimming dangerously close for a clumsy person to navigate. I’m concentrating so hard on not electrocuting myself that I almost miss our second rhino, grazing nonchalantly on the other side of a dew-spangled clearing. His clipped horn steals some of the majesty from the moment, but better ugly than dead. Moneni and Sabelo are analysing everything – footprints, fences, tracks. The difference between this and your usual bush walk is striking – bushpig and kudu tracks are glossed over, whereas one unfamiliar boot heel can result in 15 minutes of analysis. Later that day, I got a glimpse of what happens if their diligence was to fail.

As a low, curdling storm rolled in, I was being rained on in the back of the Land Cruiser and trying to dodge malicious thorn branches when something bright and red caught my eye, obscene between the browns and greens and greys. Hazard tape. You never forget your first crime scene. Two rhinos were poached here in 2014. Although bushpigs have cleaned up almost everything but wizened hide and brown-white bones, there’s not much to be done about the smell of ‘dead seal’ and a feeling of sad poignancy. Vertebrae are littered around, sprouting like giant mushrooms from the ground, interspersed with ribs the length of my torso.

The gruesome remains of two rhinos.

Over rice and pilchards that evening, Moneni tells me, ‘When a rhino is poached, it’s like losing a colleague. Or a friend. It’s like…’ He mimes blood pumping out of his heart. Sabelo dips white bread in his tea and tells me a little about their life outside here. He used to work on a mine, but says he’d never go back. It was too dangerous. I try to stretch my Zulu into a shape big enough to wrap around danger, or politics, or Marikana, but it deflates into silence. He shrugs. ‘Life is better above ground.’

Before visiting Somkhanda, I’d have told you that with massive corporate investors (as well as the shoutiest Facebook warriors), rhino conservation didn’t need my help. South Africa is not short of crippling injustices, and not all worthy causes have such an iconic mascot. But being on the front lines has given me an insight I could never have gleaned through a computer screen. What’s being fought for at Somkhanda is more than our wildlife; it’s history, heritage and a future legacy that will say we tried and didn’t fail.

View over Somkanda Game Reserve.

Getting to Somkhanda

Fly to King Shaka Airport, and drive along the N2. Pass the entrance to Phinda, and after Mkuze take the dirt road (R69) on your left. Then it’s a 17-kilometre drive to the gates of the reserve.

When to go

The standard rule about the best game-viewing being in winter still applies, but the bush is all brown. Rather go in autumn, when the trees are green but thinning, and the lack of water is starting to push animals towards waterholes.

What to do

Track rhinos with the rhino monitors, as well as do game drives and guided bush walks. Rhino tracking costs R350 per person for three to four hours.

Where to stay

Kudu Lodge is a mix of African décor and Lord of the Rings, with dark knobbled wood and wicker lampshades. The honeymoon suite has a Jacuzzi. There are also three self-catering rondavels, which are larger and more isolated. Scotia Camp has two options: either bring your own camping equipment and set up your own camp or use the camp provided, which includes a full kitchen tent with a gas fridge and a two-plate cooker. Scotia Camp has two flushing toilets and two gas showers.

Cooking in the communal kitchen at Kudu Lodge, used by self-catering guests, is a unique bush experience.

Full board at Kudu Lodge, including breakfast, lunch, a two-course dinner and daily activity (excluding rhino monitoring), costs R850 per person per night sharing. The self-catering rondavels, which have a communal kitchen, cost R350 per person per night sharing. Camping at Scotia Camp with your own equipment costs R80 per person per night, and with equipment provided R150 per person per night.

Contact: Tel 033 234 4466, somkhandagamereserve.co.za

Eat and drink

For self-catering guests, the shared kitchen is beautiful and big, with a gas hob, fridge and freezer. It’s best to stock upon supplies at Mkuze (an hour away) for everything you need, including salt – there’s nothing but coffee, tea and sugar provided. There’s also the lodge restaurant, which serves simple meals such as chicken pot pie on a rotating menu, but if you’re not staying at the lodge you must book in advance.

The tap water comes from a borehole, and isn’t drinkable – though there’s drinking water supplied in the kitchen.

Need to know

Vodacom reception is patchy – buy a CellC SIM card if you really need to be in contact. You’ll definitely need a 4×4 to navigate the tracks, and there’s no recovery team should you get stuck (though they do have basics like tyre plugs and an air compressor).

What to pack

Even though we visited in summer, it was chilly at night. Bring sandals, as although the lawn looks inviting, it’s peppered with thorns.

This article first appeared in the February 2015 issue of Getaway magazine. All prices were correct at time of publication, but are subject to change at the establishments’ discretion. Please confirm with them before travelling. All photos by Teagan Cunniffe.