On the edge of the DRC is a place where nature puts on such a show, it ignites passions in rangers and visitors beyond compare. Welcome to Virunga National Park, home to more species of wildlife than any other reserve in Africa.

At the SenkwekweCenter, Mattieu Chamavu connects with an orphan gorilla rescued from poachers who killed its family. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

‘You’re still alive!’ laughed Daniel Hanamali, our local guide. We’d just returned from walking in the emerald forests of Mount Mikeno in Virunga National Park. Daniel was waiting for us, a portly Congolese man with a penchant for pranks. ‘I’m so glad you’re still alive,’ he chuckled again, shaking each of our hands until they almost hurt. Daniel’s greeting was to become the comical mantra of our trip to eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In the mornings we’d hang out with mountain gorillas and peer through our binoculars at luminous Ruwenzori turacos. In the afternoons we’d track chimpanzees and walk through fertile fields and villages, welcomed by young and old. As the tropical sun set we’d return to big bottles of Primus beer and sit around the fireplace at the park’s upmarket Mikeno Lodge. Daniel would be there, with his usual greeting: ‘You’re still alive!’

Apparently, the DRC is one of the most dangerous places in Africa. We all laughed with Daniel because Virunga will do that to you. The park pulsates with a life force that oozes into every cell of your body. Nature puts on its seductive best and whispers sweet nothings in your ear all day long. It’s irresistible to anyone who loves nature. It’s also the most diverse terrestrial protected area in Africa: half of all of sub-Sahara’s biodiversity is found here.

Tourists stand atop the active volcano of Nyiragongo. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

Think about that. Half of Africa’s stupendous species list is found in Virunga’s 7800 square kilometres. That’s less than half the size of Kruger. It’s home to almost 300 endangered mountain gorillas, almost a third of Africa’s population. But there are also 21 other primate species, the most of any region on the planet. And to top it off, Virunga is the oldest national park in Africa (founded in 1925) and was the continent’s first World Heritage Site.

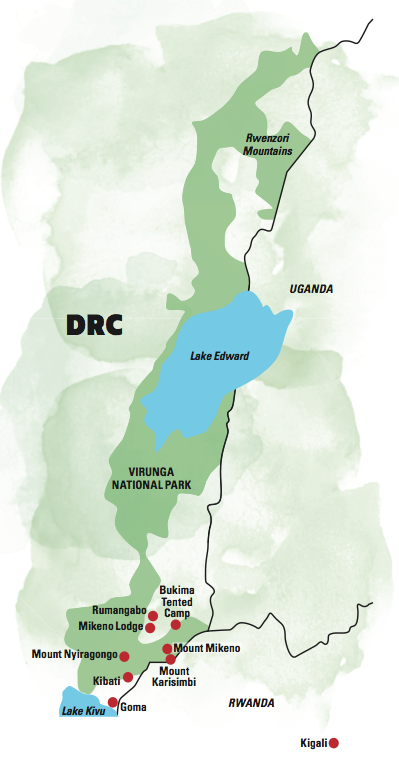

This diversity is due to a huge range in habitats and its position on the equator. Rainfall is never a problem and the park is slap bang in the middle of the Albertine Rift, atop extremely fertile volcanic soils. In the north, the five-kilometre-high Rwenzori Mountains are permanently snowcapped and strewn with glaciers. In the centre are the Rwindi plains, home to Cape buffalo, crocodiles, elephants, hippos, lions and other usual safari suspects. Alongside is Lake Edward, the smallest of Africa’s great lakes, but still 2300 square kilometres (as big as Luxembourg) and home to hundreds of bird and fish species.

Nyiragongo’s lava lake is the world’s largest. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

But it’s in the south where things get really trippy. There are eight volcanoes spread over just 100 kilometres, where DRC, Rwanda and Uganda meet. They dominate the landscape, and it’s easy to see why locals believe they are home to ancient gods. Karisimbi is the tallest at 4500 metres, followed by Mikeno, Muhabura, Bisoke, Sabyinyo, Gahinga, Nyiragongo and, finally, Nyamuragira at 3050 metres.

The first six are dormant. They are also the most beautiful and where many of the world’s last mountain gorillas live, roaming and foraging in the forests on their slopes. The last two volcanoes are the shortest, and cause all the trouble. Nyiragongo and Nyamuragira are two of the most active in the world, churning up lava lakes that have erupted every couple of decades over the past century.

In 2002, highly viscous lava exploded from Nyiragongo’s southern side and flowed at speeds of up 60 kilometres per hour towards Goma, a city of a million people 20 kilometres south. The lava destroyed several hundred buildings, melted the airport runway and displaced thousands of people. More than 100 died of carbon-dioxide asphyxiation. Virunga isn’t always the fairy-tale paradise it seems.

Hiking up mount Nyiragongo to spend the night at the crater rim. The hike takes four to five hours and climbs from 1900 metres to 3400 metres. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

Nevertheless, Nyiragongo is one of Virunga’s most popular tourist attractions. We signed up for the two-day trek to the top, accompanied by park rangers. It takes about six hours to walk up the steep slope.

At the top are several huts, built on the edge of a crater rim that drops off several hundred metres below to a lava lake. Nothing can prepare you for the sight, and sound, of this burning beast. Its lava boils at up to 1200 degrees Celsius, emitting a constant low-decibel growl. It’s terrifying and mesmerising in equal measure. And yes, you will sleep above it.

The next day we walked back down and Daniel was there. ‘You’re still alive!’ We laughed, but not entirely out of mirth this time. Some of us were happy to have gotten off the crater rim, back to the gentle embrace of the forests below.

Nyiragongo isn’t the only dark side to Virunga. The region may be the heart of Africa’s natural splendour but the daggers of countless civil wars have left it bleeding. And it’s only just beginning to heal. In the last 50 years more than five million people have died in regular violent episodes.

Many casualties were from diseases such as cholera, which spread through refugee camps when more than a million Rwandans escaped to the DRC during, and after, the 1994 genocide. Many were Hutu militia, responsible for the killings and fearful of the new government’s retribution.

Virunga National Park’s director Emmanuel de Merode was shot four times by rebels, one of the challenges his team of rangers face. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

Those nefarious forces still operate in the region today. The history is enough to freak any tourist or travel agent out, but the park’s security is expertly managed by more than 600 highly trained rangers. ‘We have to be clear about the fact that eastern Congo as a whole is not a safe destination,’ park director Emmanuel de Merode explained. ‘Security has to be taken seriously. We ensure that all visitors are properly protected. Virunga has a strict policy of caution. We’re not prepared to take risks with tourists, which means that sometimes we have suspended tourism.’

All of Virunga’s rangers are trained by Belgian special-forces instructors, and every group of guests is accompanied by armed rangers. Conservation is war, goes the saying in Virunga.

‘We’ve had close to 10000 visitors in our care without a single security incident,’ says Emmanuel. ‘There have been incidents with visitors outside the park who haven’t been in our care, so that’s why we strongly advise tourists contact us before they come and we will arrange security for them.’

Given all the negative press about the DRC, it’s easy to think that anyone would be mad to visit Virunga. Daniel’s comical greeting wasn’t entirely a joke: people do die here from attacks. Foreigners aren’t exempt; Emmanuel himself was shot four times in an ambush north of Goma in 2014. But these days violent episodes are sporadic and usually away from tourist areas.

During our trip, I never once felt unsafe. Most people we met were friendly, welcoming and polite, and only too happy to have tourists in their country. But be warned: travel in DRC can be unsettling for first-timers. The country has one of the lowest GDP-per-capita figures in Africa; the average person earns no more than the equivalent of R6000 per year.

Congolese soldiers keep watch in the forests amid an ever-present threat of armed militia. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

The state of infrastructure and roads is abysmal, even by African standards. The demand for natural resources is a huge source of concern and conflict – armed militias profit from illegal charcoal and fishing industries. Virunga itself is surrounded by agriculture and hundreds of villages. For all its natural splendour, it’s a small island of immense natural resources in a sea of humanity at odds with itself.

For visitors, though, the park’s wildlife is more than enough to compensate for the risks. Potentially, it is also the country’s greatest hope. Leading the impressive cast of characters is the mountain gorilla. Virunga’s population of almost 300 is critically important to the species’ survival. And more tourists are coming every year to see them, supplying much-needed funds for conservation.

‘Yes, Virunga is definitely not Kruger, Serengeti or the Mara,’ says Alastair Kilpin, our safari guide who specialises in leading trips to spectacular but volatile areas of Africa. ‘It offers something so different. If you’re tired of the typical safari, then Virunga will blow your mind.’

‘Besides, if you come here, your money is paying directly for the conservation of the park and the support of the surrounding communities. You can see your money actually making a difference. Gorilla trekking in Rwanda and Uganda is the only reason there are still mountain gorillas in those countries. In Rwanda, tourism is now the biggest earner of foreign exchange. Gorillas are the main reason tourists come.’

This female gorilla lay down two metres from me, nestling a baby in her arms. Her eyes glowed with maternal love. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

Trekking in DRC is cheaper than both Rwanda and Uganda, and now that things are relatively peaceful, more adventure-seeking tourists are coming. One misty morning, we began our trek at Bukima Tented Camp on the slopes of Mount Mikeno. Several armed rangers led the way. After an hour of walking, we linked up with trackers who had set out earlier in the morning to find the Humba family of gorillas, one of four that are habituated to humans.

Before we realised it, the silverback was five metres from us. He turned to look at us briefly, not really caring that we were there. A few adult females scuttled past us, one of them sheltering a two-week-old baby under her chest.

Ordinarily, wild gorillas would not tolerate our presence. It’s only after years of habituation by rangers and researchers that humans can earn their trust. The mom and her baby went to lie down in a clearing, just a few metres from us. We sat down and watched. She closed her eyes, dozing, sheltering her sleeping baby on her tummy.

The slopes of this dormant volcano (Mount Mikeno) are home to almost 300 mountain gorillas. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

Time is relative, and when you spend it with gorillas, hours become seconds. A permit allows just 60 minutes with these iconic animals, but it feels like 60 seconds. Although immensely powerful compared to humans, gorillas are largely gentle, peaceful creatures who feed mostly on a vegetarian diet.

These unassuming giants of the forests seem to be happy and content with their existence. Violence is a rare last resort as a means of resolving conflict. We may share 98 per cent of our DNA with gorillas, so we look uncannily similar, but our behaviour is very different indeed.

We left the Humba family, walked back down Mount Mikeno, and there was Daniel, greeting us in his familiar way. We felt more alive than ever.

Plan your trip to Virunga

Getting there

Fly Johannesburg to Kigali on RwandAir (approximately R6000 return, a three-and-a-half-hour flight). rwandair.com

The next morning, transfer via road to Gisenyi, on the border of DRC. The drive takes about three hours and costs about R1300 per person for a vehicle taking four people. Accompanied by a guide, the border crossing to Goma is usually quick, friendly and efficient, taking about half an hour. The following morning, transfer via armed ranger escort to Rumangabo (prices vary depending on group size and time of year), the park’s headquarters, which is about 80 kilometres north, or about two hours’ drive.

When to go

There are two rainy seasons, from October to November and from March to May, but it can rain at any time. The best is to visit Virunga between December and February, when there is a lower chance of rain, there are fewer tourists, the skies are clear and the landscape is particularly lush. Also, gorilla permits are discounted during this time.

Need to know

Accepted currency in the DRC is US dollars. Ensure that you have enough cash on hand as credit card facilities aren’t always available. South Africans need a visa for Rwanda (about R400, payable in dollars at the airport) and can pre-arrange a visa for DRC (R1200) and a permit via Virunga National Park’s tourism office. visitvirunga.org

For everything else, including transfers, accommodation bookings, border crossings, wildlife and general sightseeing, the advice of a knowledgeable safari guide is essential. Given its recent turmoil, eastern DRC can be a tricky place to visit, so it’s important to plan your trip carefully. If it’s your first time in DRC then it’s easiest – and offers the most peace of mind – to travel with an experienced guide. Contact Alastair Kilpin from Mammoth Safaris in South Africa for a customised trip to Virunga National Park. 0781529479, mammothsafaris.com

Gorilla trekking

After chimpanzees and bonobos, gorillas are our closest relatives. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

Virunga’s gorilla treks begin mostly on the western and northern side of Mount Mikeno. Day treks start at Bukima and permits can be arranged for between R2600 and R5200 per person, depending on the time of year (compared to Rwanda’s R20000 and Uganda’s R8000). The trek begins around 10:00, and can take anywhere from two to five hours, depending on where the gorillas are roaming on that day. Overnight at either Mikeno Lodge in a room or Bukima Tented Camp, which is a little simpler and on the edge of the forest. Both options cost R6000 for two sharing, full board. visitvirunga.org

Volcano trekking

In the bowel of Mount Nyiragongo, is a seething lake of lava. Photo by Scott Ramsay.

The overnight trek up Nyiragongo begins at Kibati ranger post, about 20 kilometres north of Goma on the way to Rumangabo, so it’s best done at the start or end of your stay. A permit costs R4000 per person, and is arranged through the park. Armed rangers will accompany you and porters can carry your gear and cameras (about R350 per person, excluding gratuity). Water is included but food and gear hire is extra. visitvirunga.org

Stay here

Beauséjour Hotel in Kigali, Rwanda, is a good spot to spend the night before taking the road transfer to Goma. From R800 per person B&B.

Lac Kivu Lodge in Goma, DRC, is on the northern shores of Lake Kivu and a good spot to stay before or after heading into the park. From R920 per person sharing, B&B.

Ihusi Hotel is also on the northern shores of Lake Kivu in Goma. From R1100 per person B&B.

This story first appeared in the July 2017 issue of Getaway magazine.

Our July issue features the best places to stay in the Midlands, budget family breaks in Durban, and the best (and mostly free) things you have to do in New York.